By Esther Johnson

‘And then … all the world began to roar.’ Private William Finlay, Durham Light Infantry Regiment and Lincolnshire Regiment World War I is still seared into the national consciousness thanks largely to Remembrance Sunday. Most people, even those who might not consider themselves to be students of history, will know the general themes of that conflict: the devastating loss of life, the gruelling trench warfare, and new jobs for women. But during my research for a documentary I directed called Asunder (1916) I found stories from that war that had been hidden away. Like the stories of women footballers who were years ahead of their time, and a young man who was shot dead for being absent without leave.

Munitionette Footballers

On Christmas Day 1917 the citizens of Blyth in Northumberland turned out in large numbers to see Blyth Spartans play their Munitionette Cup rivals Gosforth Aviation. In aid of the Duke of Wellington Social Club’s Parcel Fund, the final score was a 6-0 win for Spartans including a hat trick from a 17-year old Bella Reay.

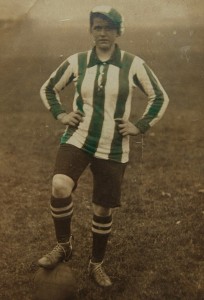

Bella, the daughter of a coal miner, was a munitions worker in the south docks of Blyth. She took any opportunity to kick a football around on the nearby sands during factory work breaks and would go on to become a whizz footballer scoring 133 goals as centre forward in a single season. During WW1 thousands of women munition workers played football, but Blyth Spartans Ladies’ FC were exceptional. The Spartans were unbeatable. In a 33-game season they won 29 and drew 4, and won the Munitionettes’ Cup Final on 18 April 1918 at Middlesborough's Ayresome Park, in front of a crowd of 22,000. In a time of austerity and fear, Bella and her team not only kept the crowds in good spirits but also raised over £2,000 for the local community.

Bella Reay. Photograph courtesy of © Yvonne Crawford.

Women’s football during the war was competitive and players needed to be highly skilled, but as the war came to an end and munitions factories closed, teams disbanded. A few women continued to play until 1921 when the FA banned women’s football on their grounds – a ban not lifted until the 1970s.

Bella married and became Mrs Henstock, having two daughters. She worked for years in the shipyards at Blyth. After retirement she was enticed back to play a few matches to help raise funds, playing for Cowpen, Cambois, and a team known simply as Blyth. She could still score goals, scoring all four in Cowpen’s 4-0 win between Cowpen and Bebside.

One of the most heartening aspects of the film research was tracking down and meeting living relatives of the individuals that feature in Asunder. During my research I spoke with Yvonne Crawford, Bella’s granddaughter, who told me how ladies football was used as a way to raise funds for soldiers wounded in the war and how Bella took to it.

‘Because the lads were going to war, they decided they would have a ladies' football team so that they could raise funds for the people who were wounded. When the boats used to come into Blyth, some of the sailors taught them how to play football, and they trained them on Blyth beach. From there it just went from strength to strength. She loved her football, she loved it. Everybody wanted her, because she was such a good goal-scorer. She played for the Munitionettes, for Blyth Spartan’s, for Northumberland, and she played for England. But all the games they played were for charity. [The players] never got nothing at all. She used to say to me, “I was good but, mind, I knew I was”.’

Shot by Firing Squad

Robert Hope was a 19-year old soldier and former shipyard caulker in Deptford, Sunderland. Robert enlisted under the pseudonym of Private James Hepple and during initial training in Ireland he met and married a 15-year-old Derry girl called Rosina McGilloway. Once Robert was posted to the 1st Battalion in Gallipoli, the couple never saw one another again. Later Robert had been shot at, shelled and gassed in some of the bloodiest battles of WW1. After fighting in the Somme, Robert went Absent Without Leave for 11 weeks. On being captured, he was charged with desertion and after a hearing that lasted just ten minutes, he was killed by firing squad on the 5 July 1917. Robert became one of the 306 soldiers shot at dawn during the conflict.

I contacted Bernard Hope, second cousin to Robert, who said, ‘I was never told about Robert when I was growing up… he was written out of our family history.’ I also met Geoff Simmons, the great-nephew of Captain Alan Lendrum, the soldier charged with shooting Robert. Geoff recounted how Alan, ‘was court martialled in July 1917 for refusing to take charge of the execution. His excuse was that, the man was known to him, and his family, and he did not believe he should have been ordered to undertake such a task. After the court martial he was demoted from Captain to Lieutenant, but in view of his continued bravery in the field this was overturned. Robert’s young wife, Rosina married again, and had 10 children – none of whom were told about Robert. Some family members in Derry were led to believe that he had run off with another woman. Such was the shame and scandal attached to what happened to him. But Rosina still thought enough of him to pay for an inscription on his grave, and she corresponded all her life ‘with someone in Sunderland’ – probably Robert’s parents.’

Archive film still © Imperial War Museum.

Geoff and myself were invited to speak at a centenary remembrance service for Robert Hope at Ferme-Olivier Cemetery, near Ypres on 5 July 2017, organised by the Friends of In Flanders Fields Museum.

Bella and Robert’s remarkable stories are just two of nine real-life accounts highlighted in Asunder, a film and music project that looks at the role of the North East in WW1. Commissioned as part of 14–18 NOW’s WW1 arts programme, the film tells the story of Sunderland and the North East, a vulnerable area during WW1, due to its shipyards and munitions factories.

Documentary Research

As an artist and filmmaker, my work is primarily focused on illuminating untold stories, so I was keen to uncover social histories that had eluded the history books. In many of my works, I have explored the effect of testimony and the use of oral history, and I wanted to extend this research to engage with the authenticity of lived experience, by researching oral testimonies with a range of viewpoints.

The objective for Asunder was to present a new way of understanding the war, and to uncover hidden social histories of both the Home and Western Fronts. The extraordinary stories, found during research in more than 20 local and national archives include accounts of the immense changes for women during the period, with new possibilities in jobs, and the challenges of working women’s suffrage activism (some women gaining the vote in the 1918 The Representation of People Act). In contrast, there are also tales of conscientious objecting, pacifism, and what it was like on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Asunder fuses archive film and contemporary footage of the North East, alongside a specially commissioned score by Sunderland’s Mercury-nominated Field Music and Newcastle’s Warm Digits. The narrative includes a sense of personal experience and emotion with the mundane side-by-side with the cataclysmic. Narration of the people's stories is by Kate Adie, with actor Alun Armstrong as the voice of contemporaneous newspaper stories. The script, written by co-producer Bob Stanley, incorporates oral histories, letters, diary entries, memoirs and newspaper items. The premiere took place on 10 July 2016 in the fitting music hall surroundings of the Sunderland Empire. (The Empire was opened on 1 July 1907 by Vesta Tilley, who is featured in the film, and was nicknamed 'Britain's best recruiting sergeant’.) The score was performed live by Field Music and Warm Digits, with vocal quartet The Cornshed Sisters and the Sage Gateshead's resident orchestra, the Royal Northern Sinfonia. The premiere date chimed with the centenary of the battle of the Somme – the largest battle of the War, commencing 1 July 1916, with a staggering 57,470 recorded losses in a single day, the largest recorded by the British Army.

Reading their words helps one to imagine what it must have been like to be in their boots...

During research I was struck by Denis Winter’s deft study, Death’s Men, Soldiers of the Great War. I was deeply touched by the detailed accounts from individual soldiers of the reality of war and trench life, ‘warts and all’. Reading their words helps one to imagine what it must have been like to be in their boots, in ‘three feet of bloody mud’. I was engrossed by the recorded oral histories of some of the characters I found in The Liddle Collection at the University of Leeds, recorded in the 1970s and ’80s. I found further recordings in the People’s Collection at Beamish Museum. In contrast to the stories of these individuals, I researched articles featured in 1914–1918 issues of the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette housed in The British Newspaper Archive at the British Library.

In documentaries and depictions of WWI, I had seen much footage of the frontline, notably in the film The Battle of the Somme (1916), shot by Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell. However, in researching rarely seen films from the war years, I wanted to go beyond the footage of the frontline. I aimed to utilise stories and period footage a viewer might not expect, such as moments of magic during the horror, and attempts at finding normality in abnormal circumstances. Distinctive archive film includes shots showing the friendships forged between young soldiers play-fighting and tending farm animals during a break from the front; a soldier at Christmas attempting to kiss a girl under mistletoe; animations of zeppelins and a ‘man-in-the-moon’. WW1 was the first major conflict played out from the air as well as on land and on the seas. For this reason I wanted to include aerial footage. With the introduction of tanks in 1916, I included the unfamiliar point of view from a tank turret. The final film incorporates footage from more than 90 films from four film archives: the British Film Institute National Archive, the Imperial War Museum Film Collection, the North East Film Archive, and the Swedish Film Institute Archive. This material was collaged with contemporary footage I shot in North East locations that were once home to the film characters.

Sunderland Aerial Image. Photograph © Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Screenings

Since the premiere, the film has screened in over 30 cinemas and community venues, and at educational events. I have received letters and short stories written in response to the film, and have been contacted by additional living relatives who on hearing about the project have shared further details about their family histories. Public screening Q&As have enabled an extension to the research, with audience members sharing their own family experiences of WW1. Asunder won the 2017 Journal Culture Best Event Sunderland award, and was finalist for Best Use of Footage in a Factual Production at the 2017 Focal International Awards.

Further screenings are planned for 2018, including a performance with live music at the Sage Gateshead scheduled for the Armistice centenary on 11 November 2018; and a screening at The Women's Library, LSE in conjunction with their Suffrage 18 exhibition.

WW1 is a truly unique period in history that turned up some truly amazing characters, all of whom deserve to be remembered for their own unique part in the story.

Asunder is co-commissioned by Sunderland Cultural Partnership and 14–18 NOW: WW1 Centenary Art Commissions, supported by The National Lottery through Arts Council England and the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Sunderland Business Improvement District, Culture Bridge North East and Sir James Knott Trust.

About the Author:

Professor Esther Johnson, Sheffield Hallam University, tells the story of an English town during World War I, with her documentary feature film Asunder.

About the Author: Esther Johnson MA (RCA) works at the intersection of artist moving image and documentary. Her poetic portraits focus on marginal worlds, revealing resonant stories that may otherwise remain hidden or ignored. Work has been exhibited internationally in 40 countries, and has also featured on television and radio. In 2012 Johnson won the Philip Leverhulme Research Prize in Performing and Visual Arts for young scholars. She is Professor of Film and Media Arts in the Art and Design Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University. For more information visit blanchepictures.com and asunder1916.uk.

About the Author: Esther Johnson MA (RCA) works at the intersection of artist moving image and documentary. Her poetic portraits focus on marginal worlds, revealing resonant stories that may otherwise remain hidden or ignored. Work has been exhibited internationally in 40 countries, and has also featured on television and radio. In 2012 Johnson won the Philip Leverhulme Research Prize in Performing and Visual Arts for young scholars. She is Professor of Film and Media Arts in the Art and Design Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University. For more information visit blanchepictures.com and asunder1916.uk.