by Dr Karli Brittz, University of Pretoria

This essay is a brief reflection on the life of a digital humanities project. Perhaps, more accurately, it is an attempt to make sense of a digitally born project and its temporality. It is not an ode, nor is it a critique. In some ways, it feels more like a eulogy. It is a testimony to the project, to mark that it was there and remember the lessons learnt from such an undertaking. Moreover, it considers a broader picture of digital scholarship and reveals my personal and scholarly disenchantment with digital humanities.

Insta-dog homepage

In 2019 I launched a digital humanities project, Insta-dog: computing Instagram’s companion species, as part of a larger research project exploring companion species on social media. The project used automatic image recognition software to assemble a close and distant reading of over 6000 images of dogs on Instagram. The computation of the so-called digital doggos resulted in new research findings, the development of interdisciplinary partnerships and even a Humanities and Social Science award for the best Digital Humanities Visualisation. However, as Insta-dog moves into post-project status, I am left to shut down the visualisation and chew over its purpose in the broader contact zone of digital scholarship.

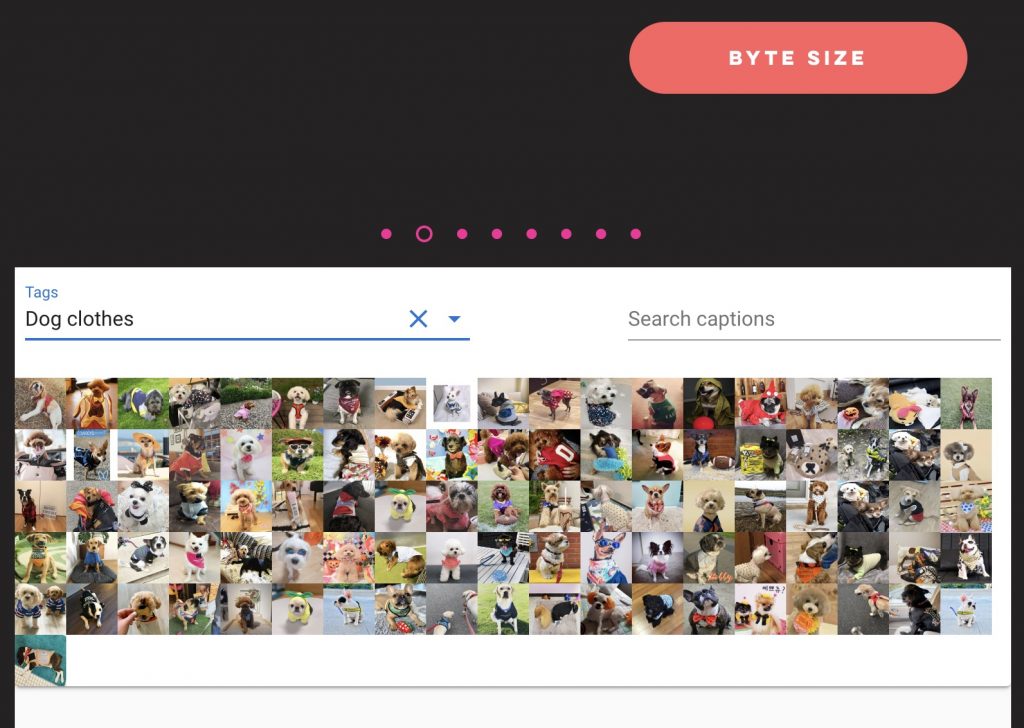

Screenshot of an example of a generated image plot.

As an early career researcher in digital culture and media, my work has always been situated within the digital and, like many others, I am in constant negotiation with technology. In the vast spectrum of what exactly constitutes digital humanities (a question I will not attempt to answer here), I think of digital humanities as an intersection where humanities scholarship and digital technology meet. In this encounter, human and technological entities connect, exchange ideas and create new networks and insights. In The Bigger Picture: What Digital Humanities Can Learn from Data Art (2018), I have also argued for the potential of these digital humanities encounters to have a powerful and transformative impact on its audiences, which extends beyond the borders of education. Digital scholarship has a responsibility to harness the influence of its technological medium to make a lasting impact on society, while critically reflecting on its computational methods. From this vantage point, I embarked on my own digital humanities journey to analyse the increasingly popular phenomenon of dogs on Instagram.

Insta-dog came about as part of my PhD research exploring companion species on social media. While studying images of dogs and their owners on Instagram (so-called dogstagrams), it became apparent that the very digital nature of the images required a digital approach of analysis. Dogstagrams, as posts on social media, are networked image-making and image-sharing entities that contain a variety of elements, ranging from metadata to captions and altered images, belonging to a wide network of information. In other words, digital computation matched the digital nature of the computed image.

Following new media theorist Lev Manovich’s mixed method approach to digital humanities, I immersed myself in the digital world of dogstagrams. Through a long-term personal learning process of engaging, exploring and experiencing, I absorbed as many posts about dogs on Instagram as I could, alongside my own dog companions. During this time, I not only observed behaviours and commonalities between posts about dogs, but also experienced hands-on what it is like to post about, follow and connect with digital dogs on screen.

Thereafter, a more technical process of computing a data set of publicly available dogstagrams followed. This included:

- Using a pre-trained computer vision API to process a large set of images to classify them into categories and supply analytical information regarding the image, including optical character recognition (OCR), labels and properties.

Processing the information provided by the API from a human point of view to identify labels significant to companion species.

Visualising the identified labels in different ways using image processing software and user interface frameworks in combination with human selection, to showcase relevant visualisations and categories of dogstagrams.

Assembling the visualisations in collaboration with theoretical research, as well as distant and close readings, into a complete platform for viewers to explore.

<

p>Needless to say, my humanities background did not prepare me for the computational skills required for this analysis. However, learning the necessary skills and persevering through technical process and coding conundrums enhanced my knowledge on the innate characteristics of social media images. By processing the images in this way, I learnt more about their nature and role in the everyday doings of companion species. It became clear that social media posts exist as dynamic entities. They carry history, meaning and specificity in their data. Moreover, through their technological essence they have the power to not only represent human-nonhuman behaviour, but also produce new meaning when we engage with these images. Additionally, images on social media are never fixed since they constantly change through interactions.

At the time, these findings were enchanting and spurred scholarly conversation. Insta-dog’s image plots assembled different categories of dogs of Instagram, further exploring companion species relations in a digital environment. The visualisations also indicated certain affordances of dogstagrams, such as responsibility and community, with the possibility of framing social media as a digital playground. Finally, it generated a textual exploration of the nonhuman agency of dogs and technology. I had subscribed to digital humanities and considered myself a fully converted digital scholar. Who could blame me? I had found a virtual world that extended my research and even my dogs were allowed along for the ride.

After Insta-dog’s official release, however, the digital humanities bubble started to burst. It became apparent that the real challenge with such a digital humanities project, which is constantly generating digitally born research, is its maintenance. Traditional academic publications are published, set free into the world and do not require much upkeep. They are preserved in their finality. But a digital humanities project is never final. Its digitality means that it is always in a state of continuity. To complicate matters, Insta-dog was double-layered in its digital nature: a digital project computing digital data.

Thus, maintenance for Insta-dog was twofold and increasingly complex. Firstly, successful image plots required a constant upkeep of the data set of dogtstagram images. Since the images are dynamic and embedded as social media posts on Insta-dog, they could be removed, edited or converted to private accounts without notice, causing missing images and errors in the plots. In other words, the data set had to be manually checked and managed to ensure the posts remained valid and usable. Secondly, the project’s backend needed regular adjustment based on a stream of third-party updates and API requirements (from both Instagram and Google Cloud Platform).

As time went by, other problems arose. Digital space costs time and money. While, Insta-dog was initially externally funded, no funding was going to maintain a lifetime worth of charges to take up space on the Internet and analyse data via an API. As an early career researcher between positions and research grants, costs became my own personal responsibility. Additionally, the supposedly durable digital project proved to have some corporeal concerns. Some of the key dogs featured on Insta-dog and Instagram, had, sadly, passed away. Although eternally embedded in their social media status (if owners did not remove their accounts), preserving these animals as part of a research project raised several ethical questions. If the dogs are no longer part of our earthly and technological encounters, can they still teach us about companion species relations? In my view, it made a difference to the findings and discussions.

As funding dried up and ethical questions grew, the time spent to maintain the project outweighed the knowledge produced. Insta-dog’s days were slowly coming to an end. But how do you close a digital humanities project? Do you simply shut it down? Sure, it’s possible, however, there are research publications dependent on the findings of the project. Are these publications still valid when the digital visualisations and plots disappear into the web’s infinite network of ones and zeros?

One of the possible solutions is to create an archive of sorts. Documenting the visualisations through screenshots and videos, hoping to store them in a more accessible manner. However, this results in an archival project that does not meet the standards and validity of a true archive and is high in media storage costs. Moreover, once a social media post is captured and stored as an image, permission should be given by the owner of the photograph, as it is no longer being used as it was publicly intended. Archiving the plots also means a loss of the entirety of the dynamic post.

Thus, at the time of writing this article, I have left Insta-dog in a moment of suspension. It is hanging onto its domain, dangling between its enchantment and disenchantment. The project still exists, with some static information on digital companion species. There are suggestions of the image plots that once was, but when viewers explore them, they might get a ‘404 error page’. The digitally born findings are no longer found. They have gone to the dogs.

In many ways, Insta-dog’s current suspended status mirrors the perplexity that surrounds digital humanities. In a post-digital society, we have become disenchanted by technology, and accordingly some scholars have lost faith in the potential of digital projects. Yet, we are still dependent on the medium, since our research is embedded in its very nature. Put differently, the digital in digital humanities has proven to be all too human. After all, as Insta-dog has shown, if research is born digital it will eventually also die digital. All that remains is some scope for critical reflection. A confirmation that Insta-dog was there. Perhaps this is the role of digital humanities: to provide a moment of suspension between the paradox of human and technology or enchantment and disenchantment. A moment of reflection, play and freedom. Thereafter, stripping the digital of its accolades and throwing it to the dogs.

About the Author

Karli Brittz is a scholar in digital culture and media studies. She is a postdoctoral candidate in the School of the Arts at the University of Pretoria, where she teaches Visual Culture Studies and Digital Culture and Media. Karli obtained a PhD in Visual Studies from the School of the Arts at the University of Pretoria and received the NIHSS award for best digital humanities visualisation project in 2021.