Paul Wilson, curator of radio at the British Library, provides a tour of the national radio archive and explains its ambitions for the radio archive of the future.

About the author: Paul Wilson has worked with the British Library's music radio collections for many years and since May 2009 has been its Curator of Radio.

E-mail: radio@bl.uk / Twitter: @RadioCurator

Tel: 020 7412 7446

Web: www.bl.uk/listening

About the author: Paul Wilson has worked with the British Library's music radio collections for many years and since May 2009 has been its Curator of Radio.

E-mail: radio@bl.uk / Twitter: @RadioCurator

Tel: 020 7412 7446

Web: www.bl.uk/listening

NB This article was first published in the March 2012 edition of Viewfinder magazine.

"We're on the cusp of something quite dramatic happening. We’re going to go from a Crisis of Scarcity to a Crisis of Plenty – where there is so much stuff that we just don’t know where to start." - Dr Hugh Chignell speaking at the Radio Archive Summit at the British Library in December 2011.

You can sense an excitement in the air within the UK's radio research community. For those who laboured at the coalface in radio archives for decades, hammering at unyielding rock, something has finally given way. And it feels as though a rush may be starting. They used to say this coal was "ephemera" - of transient value. Not even worth saving. But now some are saying that this coal is actually not coal at all. It's gold. And there's a lot of it: a cavern of little known cultural riches waiting to be excavated and explored. Can it really have taken the best part of a hundred years to get to this point?

In recent years, academics have been bubbling over with new project ideas. They travel from far and wide to audition ground-breaking radio features. A team led by Birmingham City University are proposing the first detailed study of British jazz radio using the Library's near-complete collection of off-air recordings, while another at Salford hope to explore the development of Standard English through eighty years of speech radio. Surprisingly, it's never been done before.

… at the British Library we’re not just digitising collections … we’re also making plans for the radio archive of the future

At December’s Radio Archive Summit we also heard BBC Archivists Simon Rooks and Jacquie Kavanagh enthusing about initiatives designed to get the Corporation’s history – a vast chunk of our broadcast heritage – online: projects with such intriguing titles as Genome, Audiopedia and Journal of Record. And it’s not just the recorded programmes they’re interested in – they’re resurrecting online every transmission schedule back to the 1920s; and a wealth of contextualising content from the BBC Written Archive seems set to follow. Meanwhile, at the British Library we’re not just digitising historical radio collections as never before. We’re also making plans for the radio archive of the future.

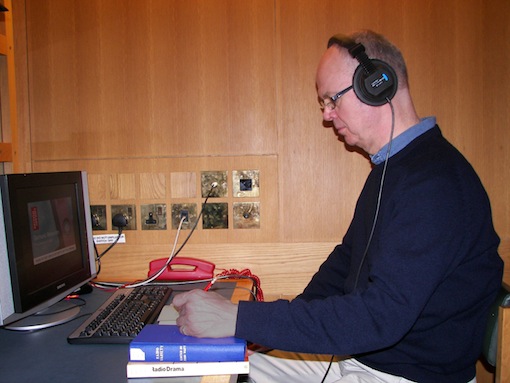

A listener within a British Library reading room carrel.

The British Library and its predecessor institutions for sound have been home to the UK’s national radio collection for over fifty years. Of course there are other significant radio archives (notably the BBC) and access services (the BUFVC), but the Library’s role as the national archive for radio is widely acknowledged. Through a combination of off-air recording since the early 1960s and selective acquisition from over two hundred donors (radio stations, producers, musicians and radio enthusiasts) we’ve amassed an onsite radio collection of nearly 200,000 hours ranging from the 1920s to the present day.

In addition, the Library’s Listening & Viewing Service in London also provides onsite listening access to the extensive collections of the BBC Sound Archive, bringing the total volume of available recordings to around 450,000 hours – 50 years of uninterrupted listening if you wanted to hear it all.

… the radio collections are a record of changing notions of archiving and of the cultural and historical value of broadcast media

This dual radio access service is complemented, as you might expect within a national library, by a third element: the UK’s most comprehensive collection of literature and non-audio media relating to broadcasting, including a near complete collection of original BBC Radio and Television news scripts from 1938 through to the 1990s.

The radio collections are a record not just of the changing nature of broadcasting since the 1920s, but of changing notions of archiving and of the cultural and historical value of broadcast media since that time. When the Library’s predecessor institution for sound (the British Institute of Recorded Sound) first began recording off-air in the early 1960s, UK radio consisted of only a handful of stations, so the majority of what was archived derived from the BBC’s national network: the predecessors of Radios 2, 3 and 4.

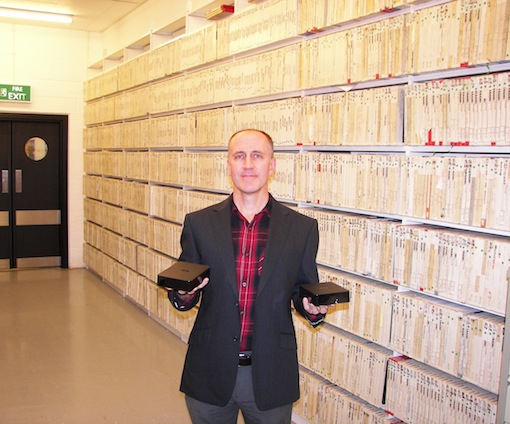

The changing face of radio archiving. Paul Wilson holds a pair of hard drives containing more than 62,000 hours of Resonance FM MP3 transmission since 2002. In contrast the shelves behind hold only hold around 2,000 hours of broadcast quality analogue stereo audio. Today more than five times this volume – 10,000 hours of radio – is being transmitted across the UK daily and the bulk of it is unlikely to be saved long-term.

Today there’s also a growing collection of independent and commercial radio content. Major collections of Capital Radio and LBC news and current affairs programming (much of the latter now accessible via the BUFVC website) are complemented by more selective collections of commercial radio from around the UK. More recently, the Library has taken the entire ‘born-digital’ archive of one of the UK’s first and most radical community radio stations – London’s acclaimed Resonance FM.

The research spectrum The collections are in constant use by researchers and students with around 40% of all Listening & Viewing Service users requesting radio recordings. Their interests are as diverse as the subject matter of radio itself, ranging across the full spectrum of arts, humanities and social sciences. Academics explore aspects of media history, such as the development of formats or radio’s contribution to national life – cultural, social and political. Others examine the work of particular producers, writers, musicians or actors. The wider public often browse for the simple pleasure of rediscovering the past.

… automated speech-to-text conversion software has the potential to revolutionise the research possibilities of radio archives

Much of it is joyous, inspiring and enlightening. Some, as a forthcoming British Library exhibition of propaganda will no doubt show, is dark in the extreme - reflecting a more sinister purpose to which radio has also been put around the world.

At the Summit we also heard from Heidi Svømmekjær and Bente Larsen of the University of Copenhagen’s LARM Audio Research Archive. This project demonstrates that, where conditions are right, it really is possible to clear very large radio collections for online research access. The British Library’s experience to date concurs with another important finding of LARM – that media research demand is largely driven by the availability of archival media. Users are also more inclined to explore digital content, which can be instantly accessed through the onsite Soundserver. Current Library policy thus prioritises our mission to get invisible radio content catalogued, digitised and – wherever legally possible – online. The ground is also being laid for plans to greatly extend access to BBC content throughout the Library’s London reading rooms over the coming year.

The bandleader and early radio star Carroll Gibbons (1903-1954) browses his collection of unique 1930s nitrate disc radio recordings – recently discovered and rescued by the British Library from a flat in central London.

Elephants & ephemera Yet a recent review of radio policy at the British Library highlighted a growing problem in relation to radio archiving nationally – an alarming gap between what is now being transmitted and what the UK’s radio archives are equipped to save. Without intervention it seems likely that only a tiny proportion of the output of the 600+ stations transmitting today will be archived for future generations. This represents a catastrophic loss not just to our broadcast heritage but also to the enormous creative and financial investments of the radio industry.

In the past, concerns about radio archiving centred on what was and was not being saved from the BBC’s (national) network radio, so the enormous output of the BBC’s Nations, Regions and Local radio services was seldom even discussed.

Graeme Garden, Barry Cryer and Alison Steadman recording 'You'll Have Had Your Tea' for BBC Radio 4 (image: Wikipedia/Flicker / CC attribution )

The other elephant in the room since 1973 has been commercial radio. Some questioned the need to save something they considered ‘ephemeral’, despite the fact that commercial stations each transmit on average 23 hours of speech content per week and some, such as XFM, feature a great deal of live and specially recorded new music.

In 2002, a still larger elephant entered the room in the form of hundreds of new community radio stations. Again, some argued that community radio is of little interest beyond the communities it serves, yet stations such as Resonance FM and Brighton’s Radio Reverb consistently produce high quality, creatively original programming.

However, the most compelling argument for saving our community radio heritage is its future research value – the richly detailed record it would provide of our lives, arts, language and dialect in the 21st Century. The success of the Library’s British Newspaper Archive of 18th-19th Century local newspapers testifies to the enormous national value of local media to future researchers.

The future radio archive So what do we want the future radio archive to look like? It may not be practical or even desirable to save everything, but at minimum we’d expect it to preserve and provide access to a genuinely representative and objective record of radio in the 21st Century. The launch of UK Radioplayer, which will soon provide access to most UK stations via a single portal, and the recently announced ‘listen again’ service for it, may prove significant steps towards making this a reality.

The future archive will be concerned with much more than the transmitted audio. Media researchers will want to know the context of transmission and the intentions of producers. The BBC’s aforementioned archive projects therefore promise to link schedule and transmission data, news scripts and a wealth of archival audio into a single online resource, ultimately connecting users to extant content within the British Library and other archives around the UK.

But future researchers will need equivalent data for commercial and community radio too, so it’s imperative that an archive of electronic programme schedules, along the lines of TRILT, is now extended to the entire UK radio network.

They'll also need new tools with which to access, organise, analyse and interpret the colossal future corpus of both audio and data. The most promising of these, automated speech-to-text conversion software, has the potential to revolutionise the research possibilities of radio archives and the means by which broadcast content is discovered and accessed. A soon-to-start British Library project aims to generate word searchable transcripts from thousands of hours of recorded radio and television audio. Whilst the potential for news and subject-based research is obvious, we also hope to show that a broad range of community radio programming, including arts and even music based formats, may be opened up to forms of analysis previously unimaginable.

Hugh Chignell's Radio Archive Summit prediction of a 'crisis of surplus' may turn out to be prescient in more ways than one. But for the radio archivist and researcher alike, this is a crisis that can't arrive a moment too soon.

Paul Wilson

Radio resources

British Library www.bl.uk/listening

BUFVC - Independent Radio http://bufvc.ac.uk/tvandradio/

LARM Audio Research Archive www.larm-archive.org/

Radio Player www.radioplayer.co.uk/