1967 saw the production of Her Private Hell, a low budget British feature that has now been given a new lease of life on video as part of the BFI Flipside series rescuing obscure movies from critical oblivion. Jonathan Rigby reviews this release below while the disc's producer, Josephine Botting, discusses what was involved in bringing this little-known film to video here.

.

2012. GB. DVD + Blu-ray. 84 minutes (plus extras). BFI Home Video. Certificate 15. Price: £19.99

About the Author: Researcher, critic and actor, Jonathan Rigby has written the following books - English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema (2000), Christopher Lee: The Authorised Screen History (2001), Roxy Music: Both Ends Burning (2005), American Gothic: Sixty Years of Horror Cinema (2007) and Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema (2011).

About the Author: Researcher, critic and actor, Jonathan Rigby has written the following books - English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema (2000), Christopher Lee: The Authorised Screen History (2001), Roxy Music: Both Ends Burning (2005), American Gothic: Sixty Years of Horror Cinema (2007) and Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema (2011).

You can’t miss him really. In fact, to seasoned students of the lower end of the British film industry, he’s unmistakable. The lean and hungry, even rat-like, appearance. The long and angular, even scrawny, frame. The small, piercing eyes. The gaunt Death’s Head features. The trademark Mephistophelean goatee. Yes, it’s Robert Crewdson, inevitably cast as the chief sleazemeister in Norman J Warren’s quietly epoch-making first feature, the torrid 1967 melodrama Her Private Hell.

Never heard of him? (Crewdson, I mean.) Well, a brief trawl through the murkier realms of 1960s cinema and TV will throw up a healthy crop of Crewdson cameos. Indeed, he played a hapless young actor – without, at that early stage, the trademark goatee – in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960). He’s the chap who has to lug a trunk across the studio floor, a trunk containing, though no one knows it yet, the corpse of Moira Shearer.

With its setting in Soho’s burgeoning sex industry of the late 1950s, Peeping Tom stands as a significant precursor to Her Private Hell, which supplants Powell’s ‘naughty photos taken above a Rathbone Place newsagents’ milieu with the swish and swinging world of celebrity photographers made famous by David Bailey and his ilk. Made famous, too, by Antonioni’s enigmatic Blow-Up (1967), which was on release in the UK while Her Private Hell was in production.

Of course, in Warren’s film, that swish and swinging world is a mere front for the oldest story in the sexploitation recipe book – the young innocent up from the country (or, in this case, another country: Italy) who, having been seduced into a glitzy and glamorous world, gains an unenviable insight into its sleazy underbelly.

In specifically British sexploitation, the story had been anticipated ten years previously in Don Chaffey’s The Flesh is Weak (1957), where another young Italian – called, as in Her Private Hell, Marisa – is plunged into full-on prostitution, not just the vaguely embarrassing nudie photos of Warren’s film.

It’s Britain’s first narrative sex film, and as such reaped massive rewards ...

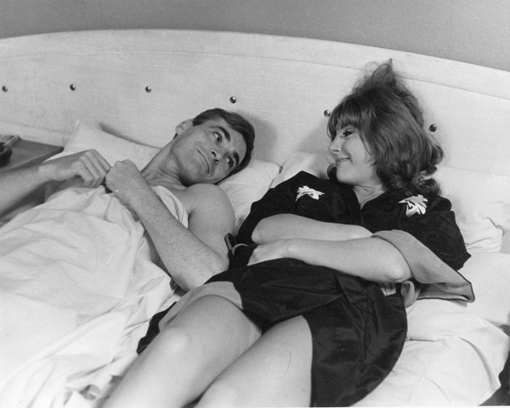

In a bigger budgeted production, no doubt Marisa would have been played by Silva Koscina or Rossana Podestà. What we have here is the lesser known Lucia Modugno (billed as 'Modunio' on-screen). Similarly, Robert Crewdson fans (a limited breed, admittedly) would have been out of luck; his role would have been nicely filled by British cinema’s sleazemeister supreme, Denholm Elliott. Again, there was no way someone like Alan Bates would be cast as the duplicitous photographer. Terry Skelton – riding moderately high at the time opposite Anna Neagle in the Adelphi production of Charlie Girl – filled the part instead. (This was shortly before he was pipped to the coveted James Bond role by George Lazenby.) And these are the main players in a picture which has one incontrovertible claim to a place in film history. It’s Britain’s first narrative sex film, and as such reaped massive rewards (having cost only £18,000 to make) in a Charing Cross Road showcase that lasted well over a year.

http://youtu.be/iMCGSgm29Gw

The producers who engaged the then 25-year-old Warren to make Her Private Hell were Bachoo Sen and Richard Schulman. (The latter would soon turn up in person in some of his own films, notably Antony Balch’s mind-boggling portmanteau Secrets of Sex.) And the result remains fascinating for the sober, even sombre story it tells, for its starkly monochromatic touches of nouvelle vague influence, and above all for its startling absence of sex. The credits play out over a modish montage of hard-to-figure body parts, Modunio is seen topless at one point, Jeanette Wild later dances topless in a seriously funky party sequence (but only in the American cut of the film) … and that’s about it. In January 1968, however, the mere fact that the characters have sex in the course of the story (albeit not on camera) seems to have been enough to ensure a box-office stampede.

The sobriety and seriousness of the story only underlines the film’s importance, because in relation to the tidal wave of movies it inspired Her Private Hell now seems like an anomaly. In just a few years British studios would sire their own sex stars (the classy Fiona Richmond and somewhat more down-to-earth Mary Millington) and become clogged with sniggering-schoolboy erotic comedies that were significantly free of eroticism or indeed comedy. (Though some of the titles remain delightful – Can You Keep It Up for a Week? and I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight spring to mind.) And at the dodgier end of the market a 1975 film like Sex Express could spawn a hardcore variant, complete with Nazi imagery, called Diversions.

All this uniquely British smut, innocent or otherwise, was triggered by the success of Warren’s modest debut film – and yet none of it is remotely discernible within the film itself. If you want to see Bob Todd in the nude, spanking Olivia Syson in a shower stall (and frankly I can’t imagine why you would), you need to watch The Ups and Downs of a Handyman, not Her Private Hell. And that in itself is a recommendation, of sorts.

As well as an intriguing anomaly, Her Private Hell is also a fascinating artefact, in which Crewdson’s baleful features are as much a period signifier as the assembled Trim Phones, Pop Art canvases, outsize Teddy Bears, and Pearl Catlin’s breathtakingly vertiginous beehive. And the film has been given deluxe treatment by producer Josephine Botting as part of the BFI’s ongoing ‘Flipside’ strand.

Presented in a dual-format edition, the print is missing the odd frame here and there but otherwise looks sumptuous (the cinematographer was Peter Jessop). It also comes with some tasty side-orders. There are screen tests featuring Udo Kier, Warren’s short film Fragment (which alerted Sen and Schulman to his potential in the first place), an even earlier item called Incident (made in tandem with future cinematographer Brian Tufano), and a 1971 Penthouse documentary called The Anatomy of a Pin-Up. Students of the form will be delighted by the appearance here of such starlets of the day as Katya Wyeth, Julie Ege and Françoise Pascal.

All in all, this is another unjustly forgotten nugget of British cinema history unearthed and lovingly polished up by the BFI.

Jonathan Rigby

To read Josephine Botting's account of the production process behind the making of this DVD, click here.