by Sarah Rutterford, the Independent Cinema Office

Interest in the British countryside surged during the pandemic. Stuck indoors, we became intensely aware of our physical and emotional need for the natural world. For many, rural Britain is a place of freedom and peace, of solace and inspiration, with an intrinsic, seemingly universal appeal. But historic depictions of the countryside as a uniformly white, mainly middle-class space both misrepresent its demographic past, present and future and lead many people of colour to conclude it isn’t for them. In 2019, a government review found that many Black, Asian and ethnically diverse people view rural England as an ‘irrelevant, white, middle-class club’.

This is not just a feeling: if traditionally portrayed as a place of innocence and gentleness, as people of colour who live in or visit the countryside know, fears of racism there are anything but unfounded. A 2001 report found that the proportion of people of colour who had been the victim of a racist crime was significantly heightened in rural areas where populations remained majority white. As well as highlighting our innate need for the outdoors, the pandemic and worldwide Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd also brought inequalities of access to green spaces into relief, highlighting the alienation and disconnect felt by millions towards the countryside.

Intended to prompt conversations about rural Britain’s past and future, the Independent Cinema Office’s Right of Way film programme challenges depictions of the countryside as definitively white and middle-class. It was inspired by the ethos behind the UK’s National Trails – part of a wider 20th century vision of resisting sweeping industrialisation, the Trails were devised as pathways to national parks for people living in overcrowded, polluted cities, a way to ‘connect people to the rural landscape’ – and the urgent need to re-explore these aims following the events of 2020.

In partnership with LUX and supported by the BFI Film Audience Network and Arts Council England, the ICO commissioned three new works from artist filmmakers Arjuna Neuman, Dan Guthrie and Ufuoma Essi exploring the historical and contemporary relationships between the UK countryside and those who have traditionally been excluded from it.

The new commissions are juxtaposed with an accompanying programme of excerpts from the regional and national film archives exploring their records of the British countryside throughout the 20th century and the development of the National Trails, offering a more institutional view of the imagery that should be preserved. Conversely, the new commissions seek to destabilise fixed notions of identity and belonging, offering glimpses of alternative rural histories and playing with time in a way that encourages viewers to look back and forwards at once, to interrogate depictions of the past and reimagine the future.

Syncopated Green (2022), dir. Arjuna Neuman

Arjuna Neuman’s Syncopated Green reflects on the history of outdoor free parties. Pitched somewhere between music video, memoir and cinema essay, it places static shots of Romantic, classical paintings of rural scenes and subjects by Constable, Gainsborough, Stubbs and others in the National Gallery alongside footage of free parties, soundtracked by rave music past and present. The film disrupts a certain kind of nostalgia and art establishment mythmaking around rural scenery – the English picturesque – but for anyone who grew up in the countryside in the ‘90s amid rave culture, may prompt nostalgia of a different kind. It reminds us that the countryside can be multiple things to different people and home to art forms more usually depicted as exclusively urban. Deploying repeated images of mirrors in rural settings, Neuman asks us to reconsider who and what images of rural Britain may contain and reflect.

black stranger (2022), dir. Dan Guthrie

black stranger follows Gloucestershire-based artist Dan Guthrie’s attempts to commune with an 18th century namesake, the mononymous “Daniel”, buried in Nympsfield on 31 December 1719 and described on a Bishop’s Transcript held by Gloucestershire Archives as simply a “black stranger”. Guthrie goes in search of the historical Daniel in his tender, thoughtful film, walking through the woods and addressing him in voiceover, attempting to flesh out the archive’s sparse record. He speculates about potential parallels between them, commiserating – ‘I know how it feels to be seen as a black stranger round here’, ‘people give me looks when I come here alone’ – and anticipating how freeing a real encounter could be for them both, allowing them to find solidarity and lose themselves in the natural world together: ‘We could just listen to what’s around us.’

As more people of colour leave expensive cities to set up home in the countryside, they become part of its future, yet face a lack of historical imagery in which to locate themselves. As musician and author V V Brown said in 2020, “the very concept of Britishness is wrapped up in images of the fields of England – and I do not represent that concept.” The word ‘urban’ has become synonymous with people of colour due to typical migration patterns, despite the fact that people of colour have also lived in rural Britain for centuries. Rhea Storr, a British artist filmmaker who grew up in Yorkshire, commented in an interview with Flatpack Festival discussing her 2018 film A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message that “I’d argue that there’s no shorthand for Black bodies in the countryside in the way that there is for Black ‘urban’ bodies. It’s an image that’s not often shown.”

While there is a lack of images of people of colour in rural Britain, its infrastructure often proffers reminders of their historical subjugation, whether via monuments and relics or estates and buildings linked to wealth from enslavement and other forms of colonial violence and exploitation. Guthrie himself made black stranger in the aftermath of his involvement with a council-led consultation in Stroud around a relic in the town called the Blackboy Clock, which ignited a culture war debate about whether we suppress awareness of our history or herald a more equal future by removing racist depictions from view.

Pastoral Malaise (2022), dir Ufuoma Essi

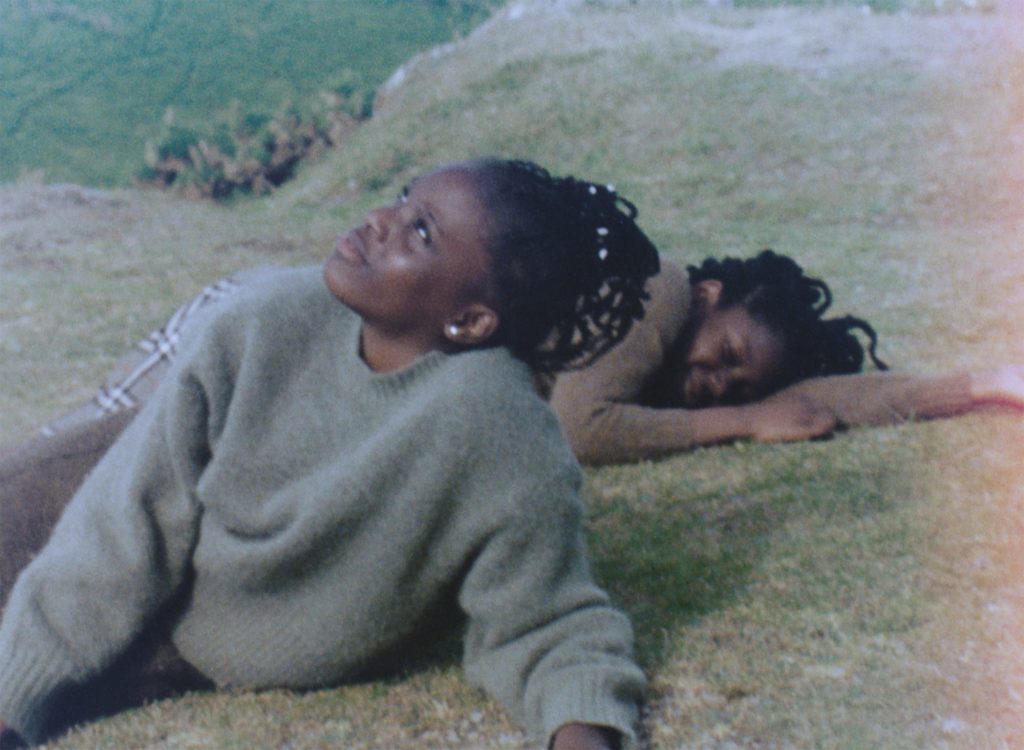

Pastoral Malaise meditates on the absences in rural environments, examined through a Black feminist approach to history and memory. Inspired by Jamaican writer and activist Una Marson’s poem Spring in England (Marson was the first Black woman employed by the BBC during World War II, her work transformed by the racism and sexism she encountered in Britain) and Dorris Henderson’s 1965 cover of popular British folk song One Morning in May, Ufuoma Essi’s film depicts Black teens roaming together across fields, hillsides and beaches, creating an imaginative relationship to the English landscape told through intimate memories and speculative histories. Like the other two films, it goes in search of kinship and community in rural Britain, alerting us to the presence of unseen images and untold stories and inviting us to consider what could be.

In 1942, the Scott Report, the government’s first comprehensive review of rural issues in England and Wales, noted “the principle that the countryside is the heritage of all involves the corollary that there must be facility of access for all.” The notion that the British countryside is, and has always been, exclusively white is a myth – a myth that is challenged by these new commissions.

Right of Way is touring UK cinemas until September and is available to book from the Independent Cinema Office.

About the Author

Sarah Rutterford is Content and Events Officer at the Independent Cinema Office.