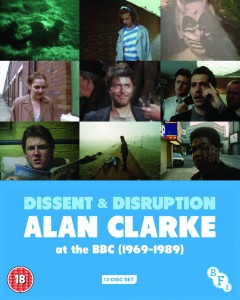

Dr Lez Cooke, Senior Research Officer at Royal Holloway University of London, takes a look at the BFI’s new Blu-ray/DVD collection ‘Dissent & Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC (1969-1989)’.

Since his death in 1990, at the age of 54, Alan Clarke has become a near-legendary figure whose work has been celebrated in two television documentaries (1991 and 2000), in books by Richard Kelly (1998) and David Rolinson (2005) and in seasons of his films and television work, but while his three feature films, Scum (1979), Billy The Kid and The Green Baize Vampire (1986) and Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1987), have been released on DVD very little of his television work has been available. Now, as part of a series of events including a BFI Southbank season, the release of previously unseen material on BFI-Player, and an article by Michael Brooke in Sight & Sound (April 2016), the BFI has put together a comprehensive DVD and Blu-ray collection of Clarke’s work for the BBC from 1969-89, supplemented by a bonus disc in the Blu-ray collection of six of Clarke’s surviving Half Hour Story plays, made for Rediffusion in 1967-68 (a seventh is included on the first disc in the collection).

The BFI has done an exemplary job in bringing together all 23 of Clarke’s extant BBC plays (a further five have not survived), together with a plethora of extras including Clarke’s untransmitted documentary Bukovsky (1977), a new two-hour documentary, Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light, comprising interviews with many of Clarke’s collaborators (divided into 12 parts spread across the 12 discs), audio commentaries, introductions to some of the plays by David Leland (from the BBC’s 1991 season), an edition of Arena: When is a play not a play? (1978) on docudrama which includes discussion of the banned Scum, Clarke’s ‘director’s cut’ of The Firm (1989), and a 200-page book containing new essays and full credits for the plays.

The BFI has done an exemplary job in bringing together all 23 of Clarke’s extant BBC plays (a further five have not survived), together with a plethora of extras including Clarke’s untransmitted documentary Bukovsky (1977), a new two-hour documentary, Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light, comprising interviews with many of Clarke’s collaborators (divided into 12 parts spread across the 12 discs), audio commentaries, introductions to some of the plays by David Leland (from the BBC’s 1991 season), an edition of Arena: When is a play not a play? (1978) on docudrama which includes discussion of the banned Scum, Clarke’s ‘director’s cut’ of The Firm (1989), and a 200-page book containing new essays and full credits for the plays.

This material has been released in two six-disc DVD volumes, covering the periods from 1969-77 and 1978-89 but it is well worth obtaining the 13-disc Blu-ray collection for the bonus disc of Half Hour Story’s which were Clarke’s earliest work for television. Like most of the collection these half-hour plays have been unavailable for many years and three have only recently been found. They show how Clarke was keen to experiment with the form of television drama right from the beginning, using low camera angles, big close-ups and rapid cutting to create a restless, distinctive style in plays which were largely two-handers written by Alun Owen, Roy Minton and William Trevor (Clarke’s three lost Half Hour Story’s were written by women: two by Edna O’Brien and one by Pauline Macaulay).

In the first part of Out of His Own Light Richard Kelly describes Clarke as ‘restlessly innovative’ in the early days, yet this could be said of Clarke throughout his career. There has been a tendency for him to be associated with a certain brand of masculine, social-realist drama shot on film, yet this collection illustrates the sheer variety of his work, including studio-based plays such as Last Train Through Harecastle Tunnel (1969), Danton's Death (1978) and Psy-Warriors (1981), location-based films such as The Hallelujah Handshake (1970), Penda's Fen (1974), Contact (1985) and The Firm, while others such as The Love-Girl and the Innocent (1973), A Follower for Emily (1974) and Funny Farm (1975) were shot on location using Outside Broadcast video. Original plays are interspersed with adaptations, including Solzhenitsyn’s The Love-Girl and the Innocent, Buchner’s Danton’s Death, Brecht’s Baal and Cartwright’s Road, male-centred plays such as Sovereign's Company (1970), Scum and Contact with female-centred plays such as Diane (1975), Nina (1978) and Christine (1987), while contemporary plays are juxtaposed with historical dramas such as Danton's Death (about the French Revolution) and To Encourage The Others (1972), which examines the injustice of Derek Bentley’s hanging in 1953. With Stars of the Roller State Disco (1984) there is even a play set in the near future.

Clarke’s restless creativity is particularly evident in his stylistic approach. In the audio commentary on Christine, one of several illuminating audio commentaries in the collection, Sam Dunn (Head of BFI Video Publishing) refers to the ‘fascinating aesthetic journey’ Clarke travelled, from the early days at Rediffusion when his signature style was all close-ups and rapid cutting, to almost the opposite in his late work: long shots, extended takes and a very mobile camera. In Part 10 of Out of His Own Light Stephen Frears mentions how Clarke was first introduced to Steadicam when he saw it being used on Walter (C4, 1982) and how it became a signature style for Clarke when he used it for the long ‘walking shots’ in Road, Elephant (1989) and The Firm. It comes as a surprise to discover that Clarke did not use Steadicam on Stars of the Roller State Disco and Christine and that the long fluid shots on those films were achieved with a handheld camera or a camera mounted on a dolly.

Elephant (1989): image courtesy of BFI/BBC.

Clarke’s stylistic experimentation was always motivated by the need to find the right style to suit the material. As David Leland said in the 1991 BBC2 documentary, Director - Alan Clarke (which unfortunately is not included in the collection), Clarke ‘worked obsessively to find a visual style for each of his productions so as to allow the viewer unimpeded access to the heart of the material’ (quoted in David Rolinson, Alan Clarke, Manchester University Press, 2005, p.2). The big close-ups and rapid cutting in the Half Hour Story plays complement the verbal sparring between characters, so that the emphasis is on them rather than their surroundings. By the 1970s and 80s, however, the surroundings in films like Penda's Fen (1974), Contact and Elephant are as important as the characters.

In her essay on Diane in the excellent booklet which accompanies the collection, Lizzie Francke notes how Clarke, even by the mid-1970s, was letting the story unfold in longer takes, quoting producer Mark Shivas on this change in Clarke’s style: ‘Now he would let the camera sit in front of people for some time, and let people move in and out of frame, and he wouldn’t cut. It prefigured his later work in some ways. And it was a seminal piece for him in terms of bleakness of style, the paring down and working within the frame, matched with the bleak subject matter.’

The Firm (1989): image courtesy of BFI/BBC.

By the time of Contact, Christine and Elephant Clarke had pared his films down to the bare essentials and the aesthetic had become ascetic. In Richard Kelly’s book Alan Clarke (1998) David Rudkin likens Clarke to Robert Bresson in his pursuit of ‘a very rigorous language, you would say a style. Except that it almost abolished style, he became a sort of Bresson figure, I think’. Clarke was certainly able to put his own stamp on whatever he did, despite the apparent eclecticism of his oeuvre. In adapting Jim Cartwright’s Road, a play which was initially going to be recorded in the studio until an electrician’s strike forced them to shoot it on location (much to Clarke’s delight), he turns Cartwright’s static monologues into ‘walking monologues’, using the Steadicam to film the characters walking through grim deserted streets as they talk to themselves and us.

There is much in this collection from which students of film and television can learn, not only about film style and television history but also about how it was once possible to create original, uncompromising works of drama in British television. Working through this collection, from Clarke’s early plays to his late work, is indeed a fascinating journey. Now what we need is for Clarke’s long unseen work for London Weekend Television to be made available on DVD.

Dr Lez Cooke