by Shane O'Sullivan

The theme of migration and borders is just one of the areas explored in a free archival resource I've developed with the BFI and BBC Archive for student filmmakers in higher education.

The Archives for Education project makes available 39 documentaries from the BFI National Archive and BBC Archive for creative reuse on course-related projects in universities across the UK. The films explore a broad range of themes from 1957 to 1992, and include work from directors Karel Reisz, John Krish, Adam Curtis, Ken Russell, Dennis Potter, Molly Dineen, Denis Mitchell and Phillip Donnellan.

Thirty-five institutions have so far joined the scheme by signing educational license agreements with the BFI and the BBC and downloading high-resolution copies of these films for creative reuse on student projects in film, television or media production courses.

At Kingston School of Art, where we piloted the project, students create documentaries or video essays in response to one of these films, integrating up to two minutes of archive clips into their own projects.

There are several films available through the scheme which address the theme of migration and borders: Eye to Eye: The Man at Dover (1957), Refuge England (1959), Return to Life (1960), The Colony (1964), London Me Bharat (1973) and Divide and Rule – Never! (1978).

The first three films look at life in Britain from the perspective of a refugee. Refuge England follows the first day of a Hungarian refugee in London and was directed by a Hungarian refugee, Robert Vas, who had come to London three years earlier with his wife and baby son following the failed uprising against the Soviets. The film was financed by the BFI Experimental Film Fund and included in the final Free Cinema programme at the National Film Theatre in 1959.

Still from Refuge England. Image courtesy of BFI National Archive.

While the lead roles in The Man at Dover and Refuge England were played by actors, director John Krish – himself the son of a refugee – cast real refugees in Return to Life, with tragic consequences.

In 1960, the Foreign Office commissioned Krish to make a film celebrating World Refugee Year. Krish rejected the initial brief (a historical survey of how Britain had helped refugees) and wanted to make a general audience “feel what it's like to be a refugee.”(1)

He wrote a film about a refugee family arriving in London and cast refugees in the lead roles. He couldn’t find a suitable family, so he constructed one. “The man I found to play the husband was Serb, the woman I found to play his wife was Croat,” he later recalled. “There were scenes where I needed them to hold hands and they could barely look at each other, let alone touch each other.” His cast didn’t speak English, so Krish worked through an interpreter and had no idea about the ethnic hostility between them at the time.(2)

The man playing the husband had been kept in solitary confinement for two years by the Russians, and his “wife” was a fascist sympathiser who had come to England with a nine-year-old son, who also appears in the film. On the final day of an arduous six-week shoot, the Serb husband and Croatian wife “so loathed each other,” according to Krish, “they spat at each other. That was the way they said goodbye.”(3)

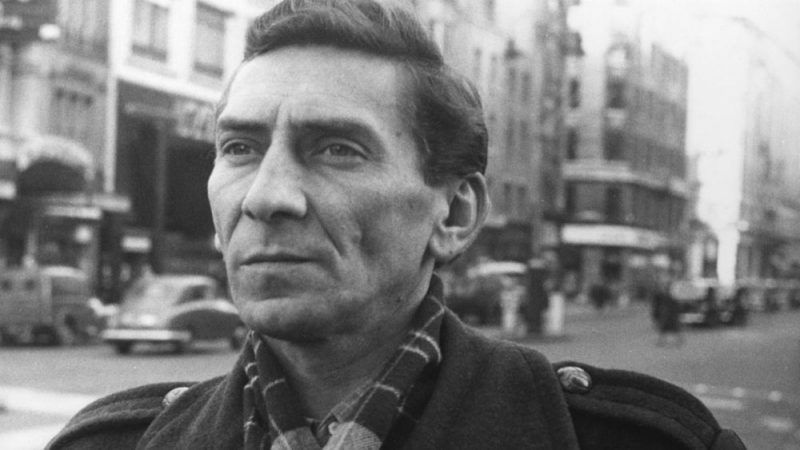

Still from Return to Life. Image courtesy of BFI National Archive.

The dressmaker Krish found to play the grandmother in the film had been forced into slave labour at Auschwitz. One day, after filming a scene with her, Krish told her “I don't need you this afternoon,” hoping she would take a rest. “She thought I said I didn't love her and she had hysterics,” Krish recalled, threatening to throw herself out of the window. Krish brought her home and “tried to make her feel wanted” by asking her to make some clothes for his children. “But it wasn't enough. She just believed that nobody loved her.” Weeks later, before Krish completed editing the film, he heard she had gassed herself to death in her tiny room in Brighton.(4)

Reflecting on the film many years later, Krish called it “one of the best films I've made, certainly in terms of directing, because these were the real thing and they are forced to play very emotional scenes with each other and difficult feelings and reactions and so on.”

But he also regretted the experience and watching the film again brought him to tears: “I just couldn't stand what I'd done. I realised how I'd used these people, how I'd manipulated them, how I'd been the puppet-master and how this woman had killed herself and how the woman playing the wife and the man playing the husband hated each other beyond belief.”(5) They are not credited in the film and remain nameless.

The story behind the making of Return to Life illustrates the ethical complexities of making a film about refugees and Krish’s candid reflections are valuable to students considering a film on the subject today. In one of his final interviews, Krish bemoaned the fact that refugees were welcomed to Britain in 1960, in stark contrast to the harsh political climate they face today.

(1) BECTU History Project - Interview No. 326 https://historyproject.org.uk/interview/john-krish

(2) Ibid.; Krish BFI interview (2003)

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) BECTU History Project - Interview No. 326

About the Author:

Shane O'Sullivan is a Senior Lecturer in Filmmaking at Kingston School of Art. His work includes the archive-driven feature documentaries RFK Must Die (2008), Children of the Revolution (2010) and Killing Oswald (2013); and the books Who Killed Bobby? (2008) and Dirty Tricks: Nixon, Watergate and the CIA (2018).

If your institution would like to join the Archives for Education scheme, please email Shane O’Sullivan: s.osullivan@kingston.ac.uk. You can find out more about the films available on the project website: www.archivesforeducation.com