by Dr Alex Hastie and Dr Michelle Newman, Coventry University

Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer and Girl in a Band: Tales from the Rock ‘n’ Roll Front Line

Introduction

Launched in 2002, BBC Four shows a range of cultural, documentary, and historical content, including TV drama series and feature films, free to air on British television and BBC iPlayer. The channel functions as an important alternative to more mainstream programming on BBC One, BBC Two, ITV, Channel 4, and Channel 5, and is a valuable source of educational content on topics ranging from Chernobyl to the Windrush Scandal.

Of particular importance and interest to us is BBC Four’s music documentaries. The channel airs and produces many music programmes which narrate British, as well as international, music cultures. Some are contemporary, such as BBC Young Musician and the Eurovision song contest semi-finals, though most are archival in nature, such as the …at the BBC series which has featured programmes on Abba, Bowie, and Dionne Warwick. There have also been documentaries about the history of hip-hop in America (Hip Hop: The Songs that Shook America) and jazz in the UK (Jazz 625: The British Jazz Explosion), and the channel’s Arena art series airs documentaries on everything from Elvis Presley to Fela Kuti.

In 2020, the BBC announced that BBC Four will become a platform for the BBC’s archives, and will no longer programme new content as part of the corporations drive to cut costs and, arguably, as part of the Conservative government’s desire to reshape the BBC. It is worth noting that they have pledged to “double arts and music spending on BBC Two". Given this political context, and the channel’s new upcoming archival role following the digitisation of many of the BBCs historical collections, it is important to consider what part BBC Four will play in the curation of national music and cultural memory, and what (and whose) stories might be lost in the reduction of new content.

In order to explore this, and to make a case for the active production of music memory through original or purchased programmes, we critique this new archival focus through a discussion of two recent music-focused documentaries aired on BBC Four: Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer and Girl in a Band: Tales from the Rock ‘n’ Roll Front Line. What these programmes demonstrate is the strength of original music documentaries to tell stories about music that resonate in ways that educate audiences about important topics: in this case, issues relating to gender and feminism. They also reveal something about the broader function of BBC Four as a vector for an actively produced public memory that encourages viewers to confront difficult histories in the present.

Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer

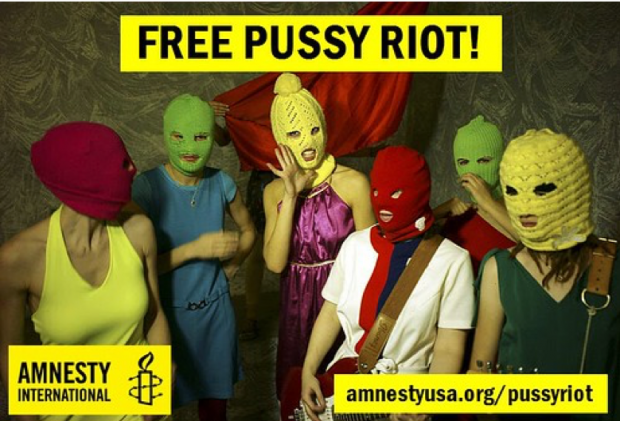

One such film is Mike Lerner and Maxim Pozdorovkin’s 2013 documentary Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer. The film is not an original BBC production but was purchased and screened as part of BBC Four’s Storyville documentary series – something which thankfully continue as part of BBC Films. As with many of BBC Four’s music documentaries, Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer is about much more than music. Pussy Riot themselves are about much more than music. They are a punk protest group who formed in 2011 after the return of Vladimir Putin to power in the Russian Federation, in order to protest his power and that of the Russian Orthodox Church though punk rock. More broadly, their protest performances in public spaces (you can see a clip of them on YouTube) revolve around women’s liberation and LGBTQ+ rights in Russia, resonating around the world, particularly after their arrest, trial and sentencing for ‘hooliganism motivated by religious hatred’ which attracted global attention (including their representation by Amnesty International). The film focuses on exactly this: the court case. In doing so, the film tells a wider story about the recent history of Russia and its narration in global media.

Figure 1: Amnesty International Campaign for Pussy Riot. Source.

Allen refers to the Pussy Riot protest performance at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour as a ‘memory event’, arguing that what followed could be seen as, “conflicting rememberings surrounding the protest event, arrest, and prosecution multiplied across national boundaries and platforms” (1). That is to say, Pussy Riot’s ‘memory event’ was remembered in ways that are more sympathetic in Anglophone and western contexts than in Russia, and that potentially reinforce national boundaries whilst, through linguistic and political translation, creating possibilities for transnational identification. In a 2014 special issue of The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, academics similarly point to the ways in which the event caused an international furore, revealing as much about Western perceptions of gender, feminism and Russia (and their cold war histories), as it does about Russia itself. Journalists and academics, including Allen, also point to how Pussy Riot’s message was mistranslated and therefore, like all memories, misremembered (see Carol Rumens’ translation of ‘Punk Prayer’ here).

The Academy Award short-listed documentary begins with introductions to some of the band – Nadia, Masha, and Katia - scored by the song they performed in the Cathedral, ‘Mother of God, Drive Putin Away’, and is punctuated throughout by a selection of songs, reminding the viewer of the power of music to upset the political and religious establishment in Russia. In the documentary, we learn that the site of Pussy Riot’s infamous protest at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour is sacred to practitioners of Russian Orthodoxy. It was commissioned by Tsar Alexander I in 1812 and took more than 40 years to build. By 1931, Stalin tore it down and replaced it with public swimming baths. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the film tells us, it was rebuilt, in an era in which Putin rose to power using the Russian Orthodox Church to his advantage. One protester against Pussy Riot recoils at the word ‘pussy’. “’Pussy’ is a devious word”, he says. “It means kitten but also the uterus. There are some other possibilities. The best translation is ‘deranged vaginas’”, he goes on, keeping a straight face. One commentator attempts to give viewers some context, saying that “punk has never really existed in Russia, neither has performance art. Nobody understands it. These ‘happenings’, actions, performances like the ones Nadia and Katia were involved in have never been well received. The West is more tolerant of it. In Russia people just don’t get it”.

Figure 2: Pussy Riot on trial. Source.

Unfortunately, there is not the scope here to go into these interesting discussions of Pussy Riot in any more detail. Nevertheless, it is important to consider what the airing of Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer on BBC Four reveals about the role of the channel in contributing to the curation of (inter)national memory-making and whether or not it can continue to fulfil this role in our turbulent future through airing archival content only. We argue that it cannot. Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer begins with a quote from Bertolt Brecht that reads: “Art is not a mirror to reflect the world, but a hammer with which to shape it”. Used to frame the radical politics of Pussy Riot, the quote also resonates with and extends to educationally-motivated music documentaries on BBC Four. We are under no illusions that the channel is a radical platform that will change the world, but it does provide opportunities for people to engage with and see the world through other people’s experiences. Whilst the digitisation of much of the BBC archives is welcome and exciting, it should not be at the expense of radical new content.

Girl in a Band: Tales from the Rock ‘n’ Roll Front Line

The second documentary is Dione Newton’s 2018 Girl in a Band: Tales from the Rock ‘n’ roll Front Line, screened as part of the Hear Her season of programmes broadcast in 2018. Marking the 100-year anniversary of suffrage for women in the UK, the season was described by the BBC as “a bold collection of documentaries, celebrating strong female voices” and was broadcast across TV, radio and online. The documentary provided a counter-narrative to the well - worn stories of rock and roll being a male only space, whilst breaking down stereotypes of ‘rock chicks’ and women as groupies or ‘hangers on’. Contributions made by women to the creation of rock music were foregrounded, telling often previously neglected stories. Examples were presented from the early days of rock and roll to the contemporary experiences of women in the music industry.

As Leonard states in her book Gender in the Music Industry: Rock, Discourse and Girl Power, “analysis of gender and rock has often begun with the premise that rock is created and performed by men” (2). Cultural memory is continually rehearsed, reproduced and shaped by and in the present. The repetition of dominant masculinised readings of the past invent a version of history that has all too frequently excluded women’s role in the production of cultural forms, in this case rock music. Cultural memory influences how groups and individuals understand the past and their own identities.

Starting with the story of the session guitarist and bassist Carol Kaye, described as an ‘invisible woman’ who had played on many iconic recordings throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Examples of her work included Ricky Valance’s ‘La Bamba’, Phil Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’, numerous Beach Boys hits, and Sam Cooke’s ‘Summertime’. She describes her experiences of having great success whilst simultaneously having to fight for her position. By capturing and presenting Kaye’s recollections of her significant contribution to the development of the rock and roll sound, the idea of rock music’s development as a performance of masculinity is disrupted and brought into question.

Other examples include punk rock band Penetration’s Pauline Murray, who not only had to combat sexism in the early days of the punk scene, but also had to resist the imposition of restrictive expectations regarding the role of women in her hometown near Durham, in the north-east of England. This story also disrupts the idea of Punk as a London or Manchester phenomena and indicates the wider sources of its origins.

Similarly, Viv Albertine of The Slits contests the story of punk as the story of men only. Albertine had previously graffitied the official blurb of the British Library's Punk 1976-78 exhibition (2016) which told (some of) the story of the origins of punk (see this article in i-D). In Girl in a Band, Albertine recounts how The Slits ‘terrified the boys’ and recounted their need to be fearless, citing the example of ‘not selling out’ to record companies who did not suit their agenda.

Other examples include Brix Smith of The Fall, Tina Weymouth of Talking Heads, Gillian Gilbert of New Order, Kim Deal of The Breeders and Jehnny Beth of Savages. The stories captured here, for the first time in many cases, make an essential and original contribution to the construction of a cultural memory where women are not only represented, but tell their stories on their own terms.

Figure 3: Brix Smith performing in The Fall. Source.

As Bennett and Rogers argue in their book Popular Music Scenes and Cultural Memory, personal memory is situated within memoryscapes related to cultural consumption (3). However, what this documentary demonstrates is that memoryscapes are also formed through cultural production. Here, the essential roles women have taken in production of musical forms that have all too often been played down or denied, are produced as an essential element of cultural memory that counters dominant and all too readily accepted one sided, masculinised version of the past, for example Nick Kent’s dismissive description of The Slits as “talentless exhibitionists...shrieking and stumbling cack-handedly through their tuneless repertoire” (4) (Nick Kent ‘Apathy for the Devil p299.)

Figure 4: The Slits performing in 1977– Talentless exhibitionists or feminist icons? Source.

BBC Four’s role as an active producer of these essential counter narratives is surely commensurate with the Reithian values to inform, educate and entertain, rather than simply and unquestioningly archive and record.

Conclusion

This short article has tried to make the case for why BBC Four, in its current format, functions as an important vector for the curation of public memory. Through two examples of music documentaries – Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer and Girl in a Band: Tales from the Rock ‘n’ Roll Front Line – we have sought to critique the BBC’s decision to transform BBC Four from what filmmaker Jeanie Finlay referred to in her critique as “a platform for quiet documentary storytelling… from new, unknown, diverse voices”, into a repository for its archives. We have argued that the production of memory is active, shaped by and in the present, and produced through original cultural productions. It is not something static and passive, living only in the past in objects that are viewed at a temporal distance. Therefore, we encourage others to reflect on what role BBC Four (and perhaps the BBC more generally) should play in the creation of collective cultural memory as a publicly-owned entity.

References

(1) Allen, Nicole Tara. “Publicizing Pussy Riot: Translating (Inter) (Trans)National Memories on the Global Memoryscape”, Southern Communication Journal, 83:3 (2018): 192- 203.

(2) Leonard, Marion. Gender in the music industry: Rock, discourse and girl power. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

(3) Bennett, A. and Rogers, I. Popular music scenes and cultural memory. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016.

(4) Kent, N. Apathy for the Devil, London: Faber & Faber, 2010.