The British Board of Film Classification celebrates its centenary this year. But what can the organisation learn from the past, and how does history inform its current business and commitment to education work….

About the Author: Lucy Brett is the Education Officer at the BBFC.

In the BBFC’s centenary year we’re delving into our archive to find clues about the very earliest decisions and certificates. We’re also celebrating our history. Cinemas are showing vintage black cards in front of films throughout the year, giving young cinemagoers a glimpse of the past and those of a certain age the chance to remember what it looked like when audiences saw a film in the 1970s or 1980s. The BFI is publishing a book, in the autumn which analysis the work of the BBFC decade by decade. The book includes case studies on key film classification decisions. A film season planned at the BFI Southbank in London in November is also designed to look beyond better known stories involving film classification, A Clockwork Orange, The Exorcist, Battleship Potemkin, for example, to a wider variety of films, from blockbusters to art house curios. Each film was selected to show how the BBFC approached films at the time of their initial classification and how attitude, culture, policies, public opinion and UK law have shifted over time.

Going back through BBFC records has yielded fascinating results. BBFC Archivist Jennifer Evans says: ‘to be honest, if you stick your hand in most paper files you'll find something interesting’.

Some files in the archive include non-film materials, such as a version of Kipling's If by post-War BBFC Director Arthur Watkins. Written for a performance in a Pathe New reel, Watkins talks of how to approach ‘caustic correspondence’ and holding your nerve whilst viewing:

If you can rule, and not make rules your master,

If you can cut, and not make cuts your aim,

If you can deal with Kant and Mrs. Grundy

And treat those two impostors just the same,

If caustic correspondence cannot hurt you,

If every picture counts, but none too much,

If you can look at Monroe and keep your virtue,

Or talk with Rank, nor lose the common touch,

If you can fill five hours of every day

With sixty minutes worth of footage run,

The cinema is yours and everything that’s in it,

And, which is more, you’ll be a Censor, my son.

Telegrams from icons of Hollywood and British film can also be found, including one from Gregory Peck regarding the film Cape Fear. In the telegram Peck describes an interview he gave in order to explain and defend the cuts made to Cape Fear by the BBFC, even going so far to say the cuts improved the film. Further artefacts include pamphlets on the problems of art and the role of censorship, press cuttings, and correspondence from film directors challenging the BBFC’s position on their works, or sometimes praising it. Files on controversial films such as Straw Dogs, Apocalypse Now and the ‘video nasties’ from the 1980s are also popular with visiting academics and journalists.

The certificates themselves changed over time. In 1932 the H (for Horrific) certificate was introduced to warn of horror themes that might be inappropriate for children. Twenty years later came age-restricted classification with the creating of the X certificate, preventing children under 16 from seeing X rated films in the cinema. In 1970 the age restriction for X-rated films was raised to 18. Other now deceased certificates include the AA, which prohibited the under 14s.

Most of the certificates we know today date from 1982 when PG, 15 and 18 were created. In 1989 the 12 rating was introduced. Thirteen years later this was modified to 12A. The 12A recommends that a film is suitable for children aged 12 and over but also lets parents choose whether to take children under 12. To help parents make that choice, the BBFC provides detailed content advice alongside the age rating on our website and free app The first film classified 12A was The Bourne Identity, though many students who remember this change associate it with Spider-Man which was originally classified 12 for cinema release before being re-classified 12A when the new certificate was introduced.

But how has sifting through our history helped us and those we talk to? Digging deeper uncovers links between film classification and wider public policy in the UK.

The BBFCs origins actually lie in Health and Safety. The Cinematograph Act 1909 introduced the licensing of cinemas, giving control to Local Authorities to grant licenses for cinema exhibition. This was originally for safety from fire in cinemas. Early film was very combustible and techniques for projection, especially the use of limelight, caused numerous fires in the early 1900s.

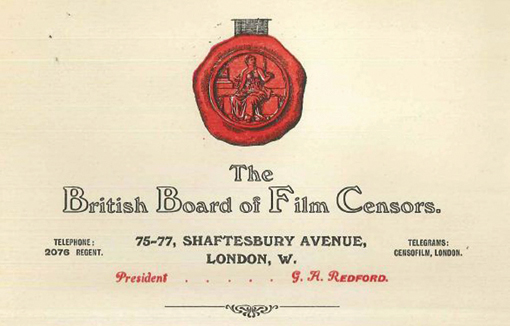

There were also issues relating to localised censorship and regional differences, as well as a lack of a standard system for the consumer and filmmaker. Such issues were live even before the First World War and the BBFC was set up by the film industry in 1912 to standardise decisions and ensure uniformity in film classification. Local Authorities retain powers, to cut, amend, reclassify or even ban works, though in practice this is rarely used outside of film festivals where works are screened sometimes months before they are submitted for classification and go on general release.

The oldest files and ledgers provide interesting titbits of information about the early BBFC, but also huge mysteries. What sort of people were the censors? Were they vicars? Were there any female censors?

The first BBFC President was G.A Redford and the first Secretary was J. Brooke Wilkinson. In the early years there were only four examiners and they viewed around 120 films a week. Films were projected side by side, an interesting concept for modern examiners who might baulk at the interference and distraction of setting another screen flickering whilst trying to view and classify another.

In terms of the mixture of examiners, by the early 1920s TP O’Connor, a towering figure in the BBFC’s history, spoke about the appointment of a ‘Lady Examiner’ following public calls for a woman’s voice in the process of censorship. He also refers, in an address to the industry, to the wide variety of distinguished candidates for the examiner’s role, and for his decision to employ men of high education and ‘sound judgement’.

There are only some answers to obvious questions. Forty films received classification certificates on the first day of 1913. But there’s no single first film rated. First on the list is About Mary of Briarwood Dell, though the exact fate of this and other titles from those early days such as Aquatic Elephants, or Interrupted Honeymoon, we will only ever be able to guess. We do know all films that day were passed U, though there was an A certificate for films recommended for adult audiences.

Some film titles can only be guessed at because of now illegible handwriting. Film archivists and historians like those at the BFI British Silent Film Festival have worked with our archive team to help decode them. Handwriting analysis isn’t restricted to silent movies. All BBFC registers, large bound books noting films, their titles and certificates (and cuts) were handwritten from 1913 until 1997.

Guesswork is key as most of the oldest film files, including details of cuts and rejections (then called ‘exceptions’) were 'destroyed by enemy action' in the Second World War. Anonymity for examiners was strong from the BBFC’s inception and there is little record of who all the examiners were.

Perhaps the best known source of information on the early days of the BBFC is the detailed literature, speeches and analysis, by T P O’Connor, the most famous being his 43 grounds for deletion. Historically the BBFC did not have written rules or Guidelines. Today the BBFC works to published Guidelines based on large scale public opinion research, specialist research and UK law. The absence of these in the early years of the BBFC was in contrast to the position of the US censors who developed the Motion Picture Production Code. Sometimes referred to as The Hays Code, it was introduced in Hollywood by the Hays Office in 1930.

T.P O’Connor was born in Athlone, Ireland in 1848 and was a journalist in Dublin and London. On his death in 1929 he was ‘Father of the House’ of Commons, a title reserved for the longest-serving Member of Parliament at any given time. When appointed President of the BBFC, one of his first tasks was to give evidence to the Cinema Commission of Inquiry, set up by the National Council of Public Morals in 1916. He summarised the BBFC’s Policy by listing forty-three examples of things which had been cut from films over the previous three years.

Cuts were made to ‘indecorous, ambiguous and irreverent titles and subtitles’; ‘drunken scenes carried to excess’; ‘the modus operandi of criminals’; ‘cruelty to young infants and excessive cruelty and torture to adults, especially women’; ‘unnecessary exhibition of under-clothing’; ‘offensive vulgarity, and impropriety in conduct and dress’. The list goes on to cover controversial politics, vitriol, the King and officers and colonies, depictions of the figure of Christ, realistic war fear, strangulation, pregnancy, profuse bleeding, opium use, and problems like eugenics, contraception and ‘race suicide’ (the reduction in an indigenous community whereby a racial group’s birth rate falls below its death rate).

Two things are clear from this list: first the majestic language of early censorship, and second some potentially outmoded concerns. However there are similarities between the concerns then and modern debate and discussion around the role of classification.

Today the BBFC practices transparency in its decisions and tests them regularly with the public. In contrast to the early days of the BBFC, a key principle of today’s BBFC is that adults should be free to choose what they watch within the law. Many of the old concerns about propriety and appropriateness of complicated, distasteful or difficult themes would, if in line with the Human Rights Act and other laws, would cease to hold relevance, especially at the 18 category.

Other concerns however, such as nudity, sex, swearing, drugs, violence, gore, weapons, criminal and dangerous imitable activities, remain on the modern classification agenda. These are now handled by appropriate age classification and clear advice for consumers about what those films contain. There are also new, more modern preoccupations, such as a desire from the public for the BBFC to be mindful of discriminatory language, themes or behaviour, and the treatment of themes like bullying, especially in works aimed at children.

The BBFC may have moved away from removing entirely references to venereal disease or birth control in educational works, but we still have to take into account the balancing act between what parents tell us they are happy for their children and teenagers to watch, even in the name of education, and what messages are useful and beneficial to those groups if treated appropriately.

The same is true of the BBFC’s own education offering. By tailoring in-house seminars and school visits to suit the age-groups of those involved, the BBFC can demonstrate the classification process and key concerns, such as violence and threat, to children of all ages. When speaking to older age groups we often contextualise the work of the BBFC through history. Similarly academics researching BBFC files often draw parallels between film classification and wider historical issues, in particular the public’s attitudes towards harm and appropriate viewing. Films themselves are informed by history in both their making and their reception and so the work of the BBFC continues to focus on balancing these to accommodate the context of a work and the way it will be received by modern audiences.

Lucy Brett BBFC Education

See also the Viewfinder reviews of related books and DVDs:

- A Clockwork Orange

- The Devils

- Film and Video Censorship in Modern Britain

- Shogun Assassin

- Straw Dogs