by Joanne Knowles, Liverpool John Moores University

The Christmas season is a very significant time for broadcasters, who are keen to offer entertainment that both makes a statement about their organisation and wins favour with audiences in terms of ratings. Channel 4’s approach to seasonal broadcasting makes a fascinating case study in this respect. Various media scholars have pointed out the eclectic character of Channel 4, which was established in 1982 as ‘a commercial station funded by advertising revenue with a public service remit’ (Bock and Zielinski, 2014, p.418). If we examine Channel 4’s Christmas schedules during its forty years on air, we can see this demonstrated. However, we can also observe its move, in the last two decades in particular, towards a more celebrity-led seasonal programming schedule where stars of the channel take centre stage, and into the establishment of its own traditions as part of this alternative and distinctive character.

The Snowman: Channel 4’s Christmas Centrepiece

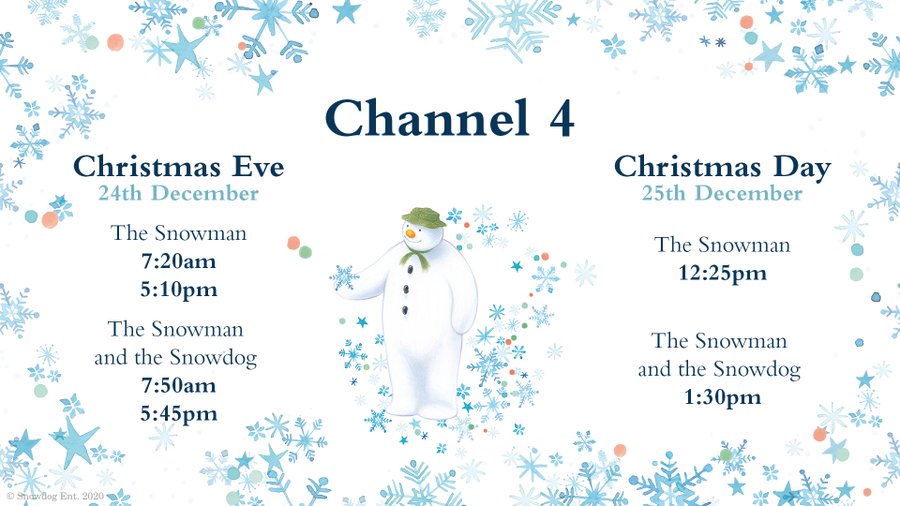

In its first year on air, Channel 4 broadcast a short animated drama which would become a staple element of its Christmas offerings: The Snowman, an adaptation of Raymond Briggs’s 1978 children’s book about a young boy whose snowman comes to life. Shown on Boxing Day that year, the programme immediately became a critical and popular success, and has been screened every year since, often with multiple showings on the main days of the holiday period. This became the centrepiece of the seasonal tradition that developed at Channel 4 as a much-loved viewing habit year after year. Its status as the emblem of Channel 4’s Christmas identity was cemented further when in 2012, the year of Channel 4’s thirtieth anniversary, a sequel, The Snowman and the Snowdog, was produced and shown on Christmas Eve – and itself has also since become a regular feature of the seasonal schedule. Consequently, the enduring presence of The Snowman at Christmas pays heed to this created tradition for the broadcaster, celebrating a key event in its history, while also addressing a new generation of viewers. It represents Channel 4’s stated purpose and identity in its commitment to enshrined broadcasting values and to producing fresh and forward-looking content.

The Snowman in schedules 2020

Animation and Imports

In addition to The Snowman, Channel 4 has made other animation for children and a family audience a standard feature of its Christmas schedules. These have included other British contemporary classic children’s productions, such as The Bear (1998) another Raymond Briggs adaptation, and Little Wolf’s Book of Badness (2002) based on Ian Whybrow’s children’s book. However, it has also consistently had an international flavour, showing Christmas stories from around the world, with features such as Christmas Crackers accommodating various animation for children including French, Canadian, or the Czech production Christmas Star in 1987. The channel’s commitment to animation blends home-grown productions with a global feel to its offering.

Beyond The Snowman, though, the animated series most strongly associated with Channel 4 is arguably The Simpsons. This illustrates how not only animation but also imported series, historically a key part of Channel 4’s offering, have also played a prominent role at Christmas. Friends is noticeable in the schedules of 2002 onwards; Channel 4 acquired the rights to Friends in 1999 and then screened the show frequently all year round until 2011. At the time Sky (the previous owners of the rights) claimed that C4 had paid over the odds for a series towards the end of its run. However, C4’s investment in comedy that attracts repeat viewers has over time generally proved to be a sound move, with many of these series- both British and American¬ – conspicuous in Christmas schedules. Christmas Eve 1992 featured both Happy Days: The Reunion and the season 10 finale of Cheers, in which Woody the barman gets married, demonstrating this seasonal preference for key episodes or retrospectives on iconic US shows and especially sitcoms.

Alternative Messages – Politics, Comedy, Channel Promotions

Channel 4’s remit when established was to be an alternative to the mainstream, by catering to ‘cultural and ethnic minorities’ and to specifically meet the needs of minority groups and interests that were not covered on other channels. Its mission to provide this alternative became an explicit part of the Christmas schedule in 1993, with the introduction of The Alternative Christmas Message, and this has continued as a Christmas Day counterpart to the Queen’s Christmas Message (which has also been shown by Channel 4 on Christmas Day throughout its time on air). It has aimed to be a space for either a public figure, or a chosen member of the public, to discuss their choice of current issues that are relevant to Christmas, but which can be more controversial and overtly political than the more cautious and anodyne treatment characteristically used in the monarch’s speech.

The alternative Christmas messages and speakers can be broadly grouped into three themes: Political messages, messages that spotlight the channel’s own stars, and comedy or satirical messages (with the potential for crossover between these categories). The political messages have included high-profile campaigners such as the US politician Jesse Jackson (1994), and Edward Snowden in 2013 on the expansion of surveillance. Some of these have been the subject of controversy, especially the 2008 message by the then president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, which received over 300 Ofcom complaints; these were felt to be have been prompted by Ahmadinejad’s public profile and accusations of tyranny, homophobia and anti-semitism, rather than the far less objectionable content of the message itself. The 2020 ‘deepfake’ alternative message apparently delivered by the Queen (voiced by actress Debra Stephenson) proved almost as controversial with the public, with over 200 Ofcom complaints about the broadcast. These seemed to be centred on the idea that it was disrespectful and tasteless rather than much genuine confusion; it seems that Channel 4’s ‘alternative’ is welcomed as long as it does not seek to tread on the toes of the ‘real’ message with direct irreverence towards the monarch.

The more political alternative messages have also frequently given airtime to family members speaking about their loss in relation to specific events or tragedies. Examples include the 2000 message from Helen Jeffries, whose teenage daughter had died of vCJD (after the outbreak of the disease attributed to eating infected beef during the mid-1990s); Neville and Doreen Lawrence, the parents of murdered black teenager Stephen Lawrence (1998); Abdullah Kurdi, father of the two-year old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi who had drowned while attempting to cross the Mediterranean sea in 2015; and Brendan Cox, widower of the murdered MP Jo Cox, in 2016. These messages can be seen as combining personal appeals from the bereaved families with a political message about the background to the events that caused their losses and a plea for change, and as such have achieved further publicity for their cause.

Comedy broadcasts have included Rory Bremner in character as Princess Diana in 1996 (with perhaps unfortunate timing; after her death in the following year, the 1997 schedule included a Diana tribute) and Ali G’s Christmas Message in 1999. Arguably these have always included a satirical and political edge to their message. Jamie Oliver’s message took the form of a sketch sending up his own creations in 2005, though with final thoughts about his aspirations for a better diet for British children. However, the channel has also regularly awarded the role of delivering the alternative message to stars of its own shows, in broadcasts that have been more slanted towards straightforward humour and in-jokes rather than politics. Examples include Barry and Michelle Seaborn from the series Wife Swap in 2003; Marge Simpson (as voiced by Julie Kavner) giving the Simpsons Christmas Message in 2004, and by midwives from the One Born at Christmas team in 2010.

Stars and Channel Identity

Over its time on air, Channel 4 has – like other broadcasters – developed an identity linked to its star programmes and presenters, and its Christmas schedules demonstrate the anchoring presence of those stars. Often these have been comedians or presenters working primarily in comedic mode: Jonathan Ross, who had begun his prolific presenting career with his chat show The Last Resort in 1987, features on Christmas Eve 1989 in One Hour with Jonathan Ross, and Tonight with Jonathan Ross is a regular festive feature in the early 1990s, before Ross’s move to the BBC. The 1990s also sees prominent specials from current hit shows or presenters, such as the Big Breakfast Christmas Special on 25th December 1994 – the channel’s light-hearted breakfast alternative had begun in 1992 – and, on the same day, a Don’t Forget Your Toothbrush special also featuring Chris Evans, a major face of the channel at the time.

As it moved into the first decade of the twenty-first century, after Evans’s and Ross’s departures from the channel, we start to see their (less laddish) replacements emerge, with Snow Graham Norton providing a festive spin on his regular show in 2001, and a seasonal version of the Friday Night Project in 2006 showing Alan Carr’s similarly rising status too. We also see the increasing significance of (male) chefs as counterparts to the celebrity presenters and comedians in the regular and seasonal schedules: from the mid-2000s, Jamie Oliver and Gordon Ramsay are central figures, with seasonal specials such as Jamie Cooks Christmas (2008) Jamie’s Night Before Christmas (2015), Gordon Ramsay’s Christmas F Word (2004), and Gordon’s Christmas Cookalong (2011) with viewers encouraged to create Ramsay’s dishes in real time as they watched.

Another 21st-century development can be seen in Channel 4’s development of its use of star names and current favourites from single programmes into a suite of programmes during the festive period. 2002 could be considered the Osbourne family Christmas on the channel, with Sharon Osborne delivering that year’s Alternative Christmas Message, plus The Osbournes, A Very Ozzy Christmas and Dinner With Ozzy (all preceded by John Osbourne, Angry Man, on the playwright, presumably added in by someone with a sense of humour) all part of the Christmas Day offering. The take a similar approach for Christmas Day 2004 when the Simpsons Christmas Message is broadcast twice, with episodes of the show sandwiches in the middle.

Documentaries, Minorities and Curiosities

In its early years, Channel 4 commissioned various documentaries on various minority interests: more recently, it has developed a particular style of documentary – for example, Big Fat Gypsy Weddings - that claims to shed light on the lifestyle of particular cultural groups, while adopting a tone that is ambivalent at best and arguably mocking and derisory. There has been considerable debate about the channel’s intentions and the consequences of these documentaries, but they have certainly attracted viewers and attention. The 2012 Christmas schedule included a strand of documentaries in this vein, often with a veneer of seasonal interest, such as The Hoarder Next Door: Christmas Special, screened on 21 December, featuring a woman with a vast collection of Christmas items attempting to declutter her house, and the Big Fat Gypsy Weddings franchise was exploited to the full with seasonal specials Carols and Caravans in 2013 and Tinsel and Tiaras in 2014. This might reasonably arouse the suspicion that these specials move away from the channel’s original remit to explore minority group and lifestyles, in the direction of making the most of popular and controversial series while they retain viewer interest.

Films

Film has always played a major role in Channel 4’s broadcasting identity, from its beginnings as a key supporter of British and arthouse film makers through its FilmFour activities, to the increasing presence in later years of comedy film. In its early years on air, Channel 4’s Christmas schedule was dominated by films and little other exceptional content – its flagship soap opera Brookside was shown on Christmas Day 1982, something which did not become common for soaps until some years later. (In contrast, Countdown, one of the channel’s other original and stalwart programmes, was not shown on Christmas Day till the final in 1987).The films shown in 1982 were established comedy classics, Buster Keaton’s The Navigator (1924) on Christmas Day and the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera (1935) on Boxing Day, with a Bob Hope double bill later that evening. However, the evening film for Christmas Day 1983 was the recent Martin Scorsese The King of Comedy (1982) an early indicator of its commitment to black comedy and satire as well as to imported film.

Patrick Stewart in A Christmas Carol (1999) Produced by TNT Productions/Hallmark Entertainment

By the late 1990s, screenings of particular festive films became part of the channel’s festive approach. 2000 marked the first Christmas Eve showing for Patrick Stewart’s A Christmas Carol, adapted for film after his one-person performance as Scrooge on Broadway and in London. This Christmas Eve scheduling was repeated in the following years for almost a decade, though from 2009 other adaptations featuring different, but equally beloved big name actors (Simon Callow, Michael Gambon, Kate Winslet) appeared instead. Other seasonal comedy such as The Muppets Christmas Carol and Gremlins have also been shown in multiple years. Films shown during the festive period are not, of course, exclusively seasonal, and Channel 4 followed the well-established practice of the other major channels by including prestigious films in its schedule, offering a mix of commercially successful films and slightly darker material with cultural high standing. It has also marked notable film dates, as with 2006 AFI’s 100 Years: 100 Cheers – ‘a celebration of the most inspiring films of all time and determined by film artists, critics and historians’.

Surprisingly Traditional? Religion and Royalty

One might expect Channel 4 to shun the religious aspects of Christmas. In fact, it has been at times surprisingly traditional in this respect, while also offering space to challenges and questioning of Christianity. In 1982, for its first Christmas Day on air, the Queen’s Christmas message was followed by an almost two-hour broadcast of a performance of St Mark’s Gospel, a one-person performance by Alec McCowen playing the various characters. However, its religious content has become steadily more sceptical, yet open to contrasting arguments, with the 2005 evening schedule including Tsunami: Where was God?, reviewing the impact of the Boxing Day tsunami of the previous year, and the 2006 schedule including The Secret Family of Jesus, a documentary on the possibility that Jesus fathered a child, and The Magic of Jesus, in which magicians attempted to perform illusions based on Christ’s miracles.

It is also perhaps surprising that Channel 4, with its development of the ‘alternative’ Christmas message, has also often drawn on royal content in its seasonal schedule. On Christmas Day 1987 it screened a 90-minute production of The Old Man of Lochnagar, adapted by David Wood from the then Prince Charles’s 1980 children’s book, and in 1989 it reran a showing of the Prince’s Trust ’88 Rock Gala, as well as the inevitable tribute to Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. As the now established presence of the Alternative Christmas Message shows, the channel’s approach rests on its referencing of the mainstream traditions to which it provides the ‘alternative’.

Conclusion

Simon Blanchard argues that Channel 4 was ‘a late-flowering reinvention of the “public service” model of television’ (2013, p.368) with its distinctive remit to offer programmes about aspects of culture – in all its forms – that were not fully accommodated on other channels. In its specifically seasonal offerings – from the created tradition of The Snowman to the oppositional mirroring of tradition in the Alternative Christmas Message - and also its general scheduling in relation to areas for which it has become known, such as controversial documentaries, arthouse and mainstream film, and its specific remit to cater for minority groups and interests, Channel 4 has developed a clear identity of its own in its festive scheduling. This identity, I would argue, is built around a hybrid sense of referencing Christmas traditions, challenging them, but also on having constructed traditions of its own, with Channel 4’s own progressing preferences at any time taking centre stage, while always maintaining space for The Snowman and the other shows that have, after forty years, become perennial favourites.

About the Author

Joanne Knowles is a Senior Lecturer in Media, Culture, Communication at Liverpool John Moores University. She is interested in popular media and culture from the 19th century to the present day, particular in relation to gender, narrative, and seasonal broadcasting. She has published on seasonality and television in the Journal of Popular Television and also for The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/why-is-the-christmas-tv-schedule-still-so-eagerly-anticipated-in-the-netflix-era-69930