Both the Old and the New Testament continue to be a rich sources of inspiration for the cinema. Dr Miles Booy considers a new history of some of the progenitors of the genre.

About the author: Dr Miles Booy was awarded his PhD by the University of East Anglia for his work on questions of authority in the representation of Christ in film. He is the author of Love and Monsters: The Doctor Who Experience, 1979 to the Present (IB Tauris, 2012) and his other publications include contributions to The Cult TV Book (2010).

Bruce Babbington and Peter William Evans felt obliged to begin their 1993 book on biblical epics with a selection of critical maulings of The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), George Stevens' much-maligned version of the life of Christ. The smug superiority with which intellectual culture disparaged biblical cinema was a discourse so entrenched that the authors felt they needed to meet it head on. Darren Aronofsky’s Noah (2014) seems unlikely to have changed this.

The past, however, is another country and they do things differently there. While cinema underwent its growing pains, and as the nineteenth century became the twentieth, religion was still one of the most vibrant forms of popular culture in the west (as it remains in many parts of the world today). Cinema adopted the imagery and themes of (predominantly) Christianity as part of its appeal. Religious subject matter became a way of 'trading up' the young medium, a way to gain the acceptance and patronage of respectable society. All of silent cinema's auteurs - from Alice Guy-Blaché to Cecil B. DeMille - worked in the genre. However, the use of religious stories did not always grant cinema the acceptance it sought. Sometimes it brought the medium into conflict with church or civil authorities. Such moments can be viewed as flashpoints when the social position of the emerging media was explicitly revealed. For all of these reasons, ever since Film Studies took a larger interest in early cinema from the mid-late 80s onwards, religious cinema has featured strongly as a point of interest.

https://youtu.be/2NP4kf_zOJs

Academic interest in cinema's earliest years coincided with a turn away from purely text-based analysis towards a greater consideration of social context (pursued via cultural studies paradigms) and in historical research which was carried out by viewing available paperwork, either that of film production companies themselves, or through wider cultural products such as newspapers where coverage of cinema's development could be found. Given the loss of so many silent films, sometimes scholars are attempting to reconstruct films, which no longer exist. Even where the footage does remain, reconstructive scholarship remains a necessity for this was a period when the film text would usually be accompanied by a speaker narrating the action or other contextualising materials. Thus, research into the scripts used by presenters or newspaper accounts of an evening’s presentation are required to give even the basic account of what audiences were shown (let alone how they perceived it). History, art, education, evangelistic potential – these were all discourses with which early exhibitors felt obliged to surround their cinematic footage of Jesus. This perhaps makes the viewing experience less different from later models than we might expect. With the development of sophisticated full-length features, those discourses would be incorporated into the film texts themselves, with promotional materials making sure that audiences and potential censors understood.

Since the turn of the millennium, the analysis of biblical cinema has been further enlivened by the contributions of scholars of theology or religious studies. Their concerns haven’t always been those of film analysts and they have often shied from the silent era, preferring the more mature narratives of the studio era and later. Bucking those trends is a new book, The Bible on Silent Film: Spectacle, Story and Scripture in the Early Cinema, written by David J. Shepherd, who was a senior lecturer in the University of Chester’s Department of Theology and Religious Studies when he wrote it but is now at Trinity college, Dublin. The book draws on a wealth of prior research by film scholars and expands greatly our sense of biblical cinema in the period, as well as containing a filmography of the period (complete with notes on DVD/archive availability), which is probably better than anything else outside of those databases accessible only in research institutions.

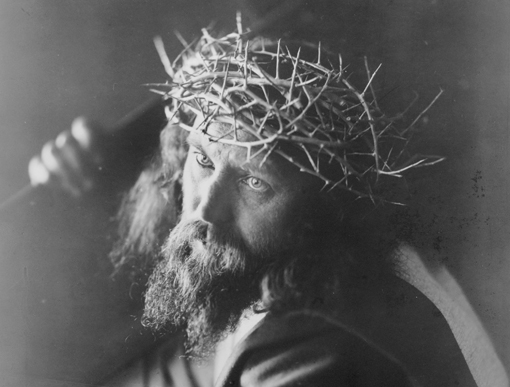

Representation of Christ from the Oberammergau Passion Play circa 1910 (image © F. Bruckmann A.-G., München / Library of Congress / CC attribution)

Shepherd’s book is broadly chronological and deals with less well-known films as well as the already-established industry milestones, which are viewed again with fresh eyes. Twenty years ago Roberta Pearson and William Urricchio established the place of Vitagraph’s Life of Moses (1909-10) within the company’s economic strategy, but their corporate analysis didn’t – for very obvious reasons – contextualise the film within the already significant tradition of cinematic representations of Moses. Similarly, Shepherd revisits the earliest screenings of Passion Plays in America, expanding on prior work by examining the scripts from which those presenting these potentially contentious images worked to explain action and offset potential objections. The earliest such presentations – following on from a tradition of magic lantern presentations – showed American audiences images of Passion plays performed in Horitz or Oberammergau and it becomes clear from the contextualising materials that audiences were left in no doubt that they were not watching a representation of Jesus per se but a representation of a sacred European play (so any theological outrage should be directed towards the European originators not the American exhibitor). The broadly chronological approach – though chapters are also organized thematically - means that Shepherd well charts the waxing and waning of international influences. Thus, as the influence of French cinema on American film production declines, D. W. Griffith takes inspiration from Italian epics. This was a period when the biblical film – not yet an epic, perhaps, but definitely punching above its weight in terms of length and scale – was tied intimately to all developments in film. That, and the breadth of Shepherd’s knowledge, means that the book can be read as an oddly skewed history of the medium in the early years. The obvious absence in the book, passion plays aside, is coverage of the many films depicting Christ himself (or Himself), the high wire of western religious representation. This is something Shepherd will presumably rectify with the same thoroughness on display here in 2015 when Routledge publish a collection of essays on the theme, which he has edited.

Nor will the research end there, I suspect. Shepherd concludes his book with a long list of future directions that the analysis of early biblical cinema might take, including that of its relationship to the explicitly evangelical early Christian film industry. This non-mainstream area of filmmaking, with its own systems of production and exhibition, is the explicit subject of a several volume history currently being compiled by Terry Lindvall under the title ‘Sanctuary Cinema’, the first volume of which covers roughly the same years as Shepherd’s book, finishing in the 1920s when radio established itself as the Christian medium of choice.

Would a Film Studies academic want to take this up as an area of study? I have my doubts, but perhaps a better question is whether American cinema will force their hand? Christians are openly sought as an audience for feel-good against-all-odds movies - The Blind Side (2009) - or violent action pics - The Book of Eli (2010); The Passion of the Christ (2004) - and biblical epic (Ridley Scott’s retelling of Moses, Exodus: Gods and Kings will hit cinemas in December, Ben Hur is due (again) in 2016). Explicitly Christian cinema has had a good year at the US box-office in 2014 with films like God's Not Dead and Heaven is for Real and even got a release around some of the UK’s independent cinemas. The world of silent biblical cinema is one where Christian themes are explicitly tied to the mainstream. Its research is obviously an historical project, but it may throw up more pointers to the future than we think.

Dr Miles Booy