Dr Louise Gentle, Nottingham Trent University, examines James Hill’s classic Born Free and its enduring influence on the teaching of higher education wildlife conservation.

About the Author: Dr Louise Gentle is Course Leader for the BSc in Wildlife Conservation. She teaches modules including Biodiversity Conservation, Behavioural & Evolutionary Ecology and Experimental Design. Her research interests include Behavioural Ecology and Wildlife Conservation. She has contributed to publications such as Bioacoustics: The International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording (2013), British Birds (2013), Conservation Genetics (2002) and Behavioural Processes (1999).

About the Author: Dr Louise Gentle is Course Leader for the BSc in Wildlife Conservation. She teaches modules including Biodiversity Conservation, Behavioural & Evolutionary Ecology and Experimental Design. Her research interests include Behavioural Ecology and Wildlife Conservation. She has contributed to publications such as Bioacoustics: The International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording (2013), British Birds (2013), Conservation Genetics (2002) and Behavioural Processes (1999).

When students start on a Wildlife Conservation degree, most of them want to cuddle fluffy, enigmatic animals such as meerkats, monkeys, and even lions. Why wouldn’t they? It is in our human nature to want to nurture animals and form a bond with them. However, by the end of the course the students have learnt how to conserve animals, and see that in most cases we need to stand back from nature and leave it to be free. This is exactly what Joy Adamson discovers during James Hill’s film Born Free (1966), the true story of Elsa the ‘pet’ lioness.

Born Free (1966) is available on dual format Blu-ray/DVD from Eureka Entertainment.

The story is set in Kenya, where George Adamson works as a game warden. One day, George is required to shoot a dangerous, man-eating lion. However, he ends up shooting its partner in self-defence, later finding that the lions had three dependent cubs that would perish if they were left in the wild. As George feels incredibly guilty about orphaning the cubs, he ‘rescues’ them and takes them home to his wife Joy whose first instinct is to cuddle the cubs. The film then shows the cubs becoming attached to the Adamsons, and vice versa.

Elsa, the runt of the litter, is hand fed by Joy and soon becomes her favourite. After a while, George’s boss decides that the cubs have become too large so, as they are also potentially dangerous, they should live in captivity in a zoo. Although upset, the Adamsons train the lions for the relocation. This involves gradual steps such as getting the lions used to a vehicle, then being inside a vehicle, then being inside a moving vehicle. However, by the time the lions are ready to by transported, Joy has become extremely attached to Elsa. Realising the bond between Joy and Elsa, and how upset Joy will be when she loses Elsa, George keeps Elsa back from the zoo. A poignant moment is when George’s boss remarks ‘you’re as much her prisoner as she is yours’. Joy replies ‘she’s not a prisoner, she’s a friend’.

Elsa lives with the Adamsons until she is fully grown. However, the time comes whereby they can no longer look after Elsa. A fantastic discussion then ensues whereby we get both sides of a conservation story. Elsa is too big to be allowed to roam about and is causing chaos. Yet, if Elsa is caged, Joy believes it will ‘frustrate her and make her vicious’. Consequently, Joy wants to set Elsa free, but as George points out, ‘you would be sentencing her to death, she would starve in the bush’. Nevertheless, Joy’s attachment to Elsa is so strong that she can’t bare to think of Elsa in a zoo for the rest of her life: ‘she’s been free too long, she would be miserable in a zoo’.

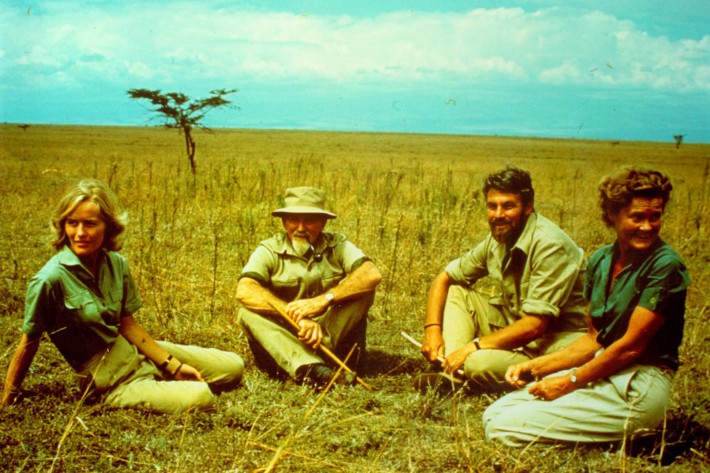

Virginia, Bill, George and Joy. Image courtesy of Columbia Pictures.

The Adamsons are given three months to teach Elsa to be wild again. They plan to release Elsa in a game reserve, but first they need to teach her to fend for herself. The Adamsons plan to leave Elsa in the wild for increasing periods of time, gradually reducing her food until she relies on them no more. However, it is quickly apparent that Elsa is unable to hunt food and doesn’t know how to behave around other lions: ‘she can’t do anything a wild animal needs to do to survive’. The Adamsons leave Elsa as much as possible, but they always return to find her in the same place, and hungry. On one occasion, they find that Elsa has been badly hurt and, although she recovers, she seems somewhat different.

Frustrated that they are unable to teach Elsa to be wild, the Adamsons have another key discussion. According to Joy ‘Elsa was born free and has the right to live free’ but George points out ‘you've done too good a job, we’ve made her too tame’. George is acutely aware of Joy’s feelings: ‘what you’re hoping is that she will stay tame so you can see her whenever you want to, but that can’t happen’ but Joy is torn between what is right for Elsa and what is right for her: ‘I know what is good for her but I don’t want to let her go’.

Elsa starts going out alone, only returning when hungry. One day the Adamsons witness her killing prey successfully, then Elsa proves time and again that she can fend for herself. The Adamsons finally take Elsa out to the reserve when she is in season, and she doesn't return to the camp.

Several months later, Elsa turns up at camp with three cubs of her own. Joy narrates ‘I was dying to pick them up and hold them but I knew that it would be wrong as they were wild and it was better now that they would remain wild’. The Adamsons sighted Elsa again many times throughout her life ‘born free and living free’.

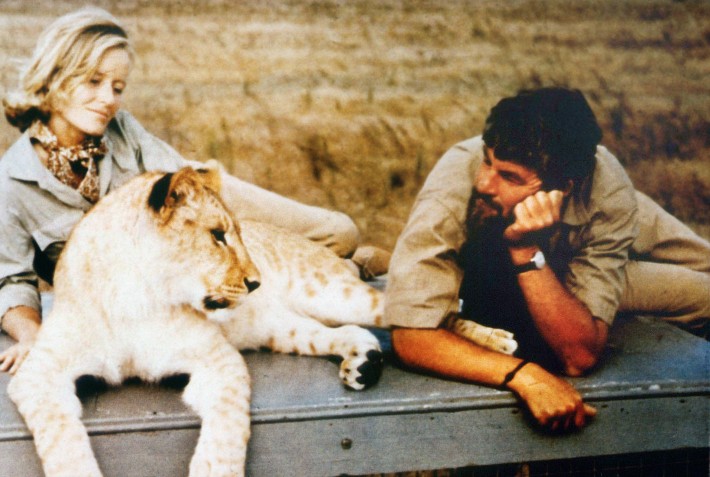

Image © Columbia Pictures.

So, they did it! The Adamsons successfully trained a tame animal to become wild again. This seminal study paved the way for many other studies, particularly within the field of conservation. Unfortunately, humans have caused destruction to the planet and a consequent decrease in animal populations. Many animals no longer have a natural habitat in which to live, so animals are kept in zoos - akin to a modern day Noah’s ark - and bred in captivity, decreasing the chance that species will go extinct. Thankfully, zoos have changed since the 1960s. No longer are they just places for entertainment, they now focus on education and conservation. Breeding is promoted where possible, with a view to reintroducing animals to the wild. Of course, this isn’t always possible as some animals are too ‘tame’, and some animals no longer have sufficient habitat available to be returned to the wild. So, some animals are destined to spend their lives in captivity. However, there is now so much enrichment (toys, mixed species exhibits, natural feeding, etc.) that abnormal, stereotypical behaviours such as pacing and self-mutilation are much reduced.

The main goal of captive breeding is to reintroduce animals back to the wild. This often involves months of painstaking training to prepare the animals for their natural environment, but without the Adamson’s work it would have taken much longer for us to realise that this was even possible. It is also key that we detach ourselves from animals as much as possible in this process, otherwise they may not fear humans, their only real predator! For example, we can now fit tracking devices to animals to see where they are and monitor how they are doing from a distance, without having to disturb them. Nevertheless, the best thing (as learnt by the Adamsons) is to manage the habitat but leave large species alone, keeping them away from human contact completely.

The story of Elsa was life changing for Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna (the actors who played the Adamsons) as they have been campaigning for wildlife causes ever since. They visited zoo ‘slums’ in the 1960s in order to improve conditions for animals. Later, they set up the Born Free Foundation with the aim of ‘preventing animal abuse and keeping wildlife in its natural habitat’. The Foundation recently revealed that the lion population where Elsa was born is only a quarter of the size that it was 30 years ago. As such, work is being undertaken to ensure that the lion population does not go extinct in that area.

This film makes you think about what is right, ethically and morally. Although we have the instinct to attach ourselves to animals, we need to learn, as Joy Adamson did, that it is better to leave animals to be wild.

Dr Louise Gentle