by Stuart Moore and Kayla Parker

Stuart Moore and Kayla Parker reflect on making their film, Father-land, on location in Nicosia

Early November 2016, we arrive in Cyprus after nightfall. We are here for an artist residency, hosted by Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre, to research and shoot a collaborative essay film, Father-land, that investigates our ideas of home and displacement. As the children of military personnel who served with the Royal Air Force on the island during the Cold War, we are drawing on our memories of a militarised nomadic childhood to explore ideas of home and displacement. Both our late fathers were stationed in Cyprus prior to its division in 1974, which followed when Turkish troops invaded and seized the northern third of Cyprus in response to a coup by militant Greek Cypriots seeking union with Greece.

Father-land film still: home from home, view from our Nicosia apartment

For the next month, our home from home is a small first floor apartment at the back of the arts centre, about a hundred metres from the demilitarised zone that cuts across Cyprus from east to west. This ‘buffer zone’, patrolled by United Nations peacekeeping forces, still separates the Turkish-occupied north of the island from the Greek Cypriot south. From the apartment, we can access a flat roof and film across the Buffer Zone and beyond into the northern territory. During daytime, we can see the houses abandoned during the intercommunal conflict that took place over forty years ago, their walls pockmarked by mortars; guard posts manned by soldiers, with their attendant flags and antennae, and the trees that have grown tall in the intervening time. At night, a huge Turkish flag, created in flashing lights, beams out from the hillside beyond the city to the north.

Father-land interweaves our personal narratives of childhood with our experiences in present day Nicosia, as we explored the empty streets and the suspended animation of the seemingly unchanging Buffer Zone, against a background of the UK isolating itself from Europe. The film also tells the story of Nicosia, as the only divided capital in Europe, and questions the concept of home, reflecting on images of conflict and bringing together the personal and the political in our post-Brexit times.

Sometimes, as a family we'd be kind of packed up with our lives kind of put into boxes and you get depending on your rank in the RAF you'd get a certain number of boxes. And so, these ones you'd then take … whatever you could fit and then that was moved out to another place or another country. And then eventually they'd all arrive. And you'd unpack your stuff… and unpack yourself. And then you'd be living in these places until your father was moved on to another posting.

(Father-land: narration)

We do not know whether our respective family histories overlapped in Cyprus, but we were interested in pursuing common experiences about dislocation and home through the artist residency. We did not set out to make a documentary about the past or present political situation on the island, but hoped to find resonances through our exploration of the place itself. The form of our film was not prescribed in its planning stage, rather, it evolved organically through the processes of its making. We drew on formative experiences of both being ‘RAF children’, uprooted from one country to another – patriarchal baggage moved by the forces of neo-colonialism. This was inflected by the uneasy stasis of the unresolved conflict which tore the island in two over forty years ago, and the ruins of the past.

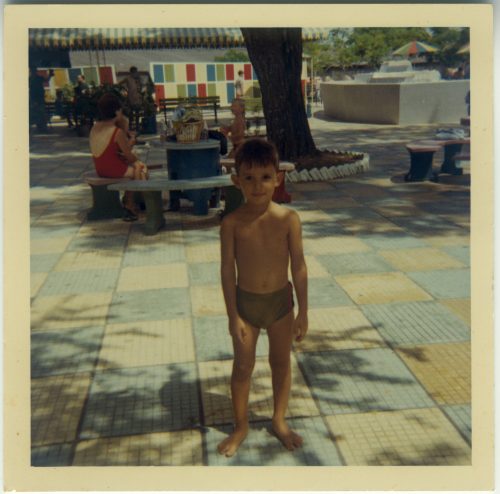

Stuart at Seletar swimming pool, Singapore

After the Second World War, in the last half of the twentieth century, the RAF maintained bases around the globe. Airmen could be posted to any of these locations, as required - sometimes for a few weeks, at other times for several years. As children, we learned that our fathers could disappear at a moment’s notice, returning home with souvenirs, but giving little explanation of what they had been doing while they were away. Family life was nomadic, and we both moved to new homes many times – usually within Britain, but also to continental Europe and the Far East. Home was often in ‘married quarters’ on the RAF base, segregated into neighbourhoods by the rank of the family patriarch: officer, NCO or airman. Families were issued with standardised crockery, bedding and other essentials which were logged out and back in after the posting was over, forming a shared domestic landscape for the extended military family – domestic uniformity. Personal belongings were always restrained by the knowledge that one day it would have to fit into provided shipping crates plus what one could carry.

Kayla on a trip to the beach in a United Nations convoy, Cyprus

Over the years these postings to distant bases have reduced for financial and strategic reasons, but a few, such as Cyprus, remain to this day. Situated in the eastern Mediterranean, the island is a strategic location and both fathers were stationed there at different times during the Cold War period. One of the authors, Kayla Parker, lived in on the island for three years as a child, when her father was working in RAF Akrotiri on the south coast. Stuart Moore’s father was deployed to Cyprus several times, whilst the family remained in Britain – he has a strong memory of a red pencil case, marked on the front with a map of the island in gold and the names of the principal towns in black, a gift from his father.

Our steady camera captures the gentle swaying of the palm trees, a scene repeated from countless windows in the old walled city. Looking towards the Buffer Zone, it reminds us of the paradox of domestic and militarised spaces co-existing. A visible aspect of the border is that the southern side remains temporary in form – rusty oil drums filled with concrete – despite remaining in place for over four decades. A large eucalyptus tree we can see from the rooftop outside our apartment has been growing freely in the Buffer Zone for several decades. Wildlife thrives in this no man’s land, a sanctuary largely untouched by human activity.

On location, the Buffer Zone in Nicosia recalled the places where we’d played as children, creating dens in the disused defensive structures of World War II that were part of the RAF camps. These now-purposeless buildings, with their crumbling bricks, rotten wood, smashed panes of reinforced glass, scattered with debris and colonised by weeds, became places of imagination, and possibility.

I find it quite comforting in a strange way, living there, because there's this border ... and although it's made out of barbed wire, razor wire, sand bags, falling to bits oil drums, broken down old buildings. It reminds me of living by the sea where I live in Britain, in Plymouth. And there’s sort of something quite comforting about living on the edge.

(Father-land: narration)

Is it possible, or even desirable, to return to a remembered past? In revisiting the sites of memory, we re-experience the dislocation of exile, feeling uprooted from home, family, ourselves – baggage that has gone astray in transit, lost and cannot be reclaimed. The residency apartment in Nicosia echoed earlier temporary homes located close to the action. Here it was the Buffer Zone, decades earlier it was in Germany facing the rolling tanks of the Soviet Union.

We hope our film will provide a contextualisation of the effects of postcolonialism, mediated through our experiences as children and as filmmakers whose histories have brushed against this divided island.

Father-land was made through the Plymouth-Nicosia artist residency scheme, hosted by Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre in Cyprus and supported by the School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Plymouth, UK, and won the 2020 British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies Practice Research Award for Essay/Experimental Film.

About the Authors

Stuart Moore is a film-maker and sound artist whose work screens internationally; he has won awards from London Short Film Festival and two SW Media Innovation Awards. Currently a 3D3 AHRC-funded doctoral researcher at Digital Cultures Research Centre, University of the West of England, Bristol, his PhD inquiry focuses on personal archives, film and memory.

Dr Kayla Parker, artist film-maker and Lecturer in Media Arts at University of Plymouth, creates innovative works for cinema, gallery, public and online spaces using film-based and digital technologies. Her research interests centre around subjectivity and place, embodiment and technological mediation, from posthuman feminist perspectives.