by Ollie Dixon, University of Bristol

Television at the Intersection of Radical Politics and Independent Film

This article draws upon oral histories and archival analyses conducted as research for my MA dissertation on Cinema Action. I would like to thank all the participants for their invaluable help in producing this research.

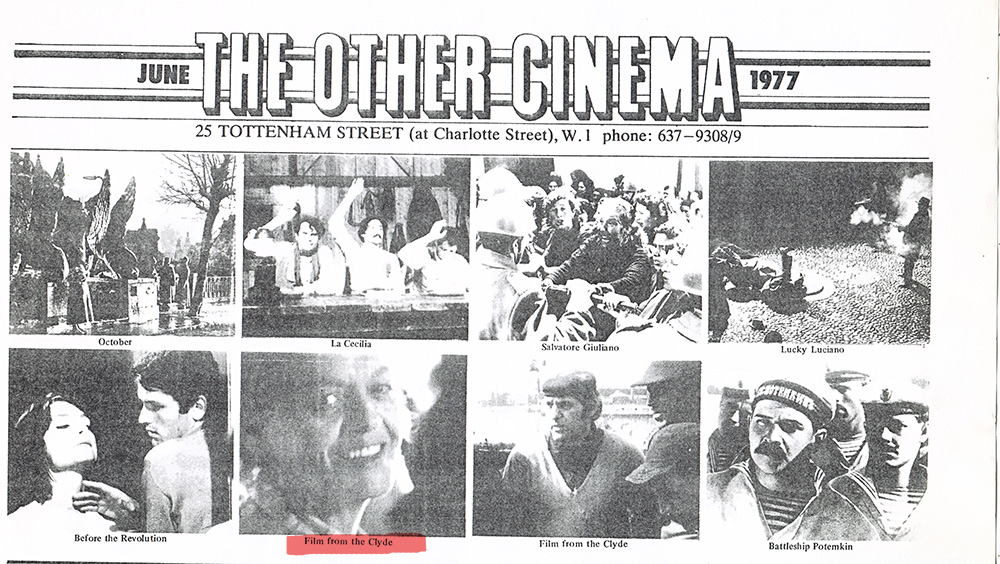

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the growth of independent film culture in Britain. During this period a heterogenous mix of artists' organisations, such as the London Film-Makers Co-Operative, film collectives, such as Amber and Cinema Action (CA), and independent distributors, such as The Other Cinema, emerged. Inspired by the revolutionary European politics of the late 1960s, international struggles against colonialism and the domestic working-class, feminist and racial justice movements, such organisations developed new forms of aesthetically and political challenging film. In 1974, these currents converged with the formation of the Independent Film-Makers' Association (IFA). The IFA aimed to represent the perspectives of this burgeoning culture and lobby funding bodies, like the BFI, BBC and Arts Councils, for greater financial support.

As government plans for a fourth television channel developed across the 1970s, the IFA campaigned for the channel to include Britain's burgeoning independent sector. The IFA's influence registered in the channel's remit for 'innovation and experiment in the form and content of programmes' and the appointment of a commissioning editor for the independent film and video sector. In 1982, the IFA's lobbying activities met further success with the establishment of the Workshop Declaration. The Declaration was an agreement between Channel 4, the Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians (ACTT) union, the BFI and regional arts associations (RAAs) that enabled ACTT members to produce, distribute and exhibit non-commercial film and video work as part of collective workshops. Channel 4, the BFI and RAAs were to fund workshops who, in turn, retained control over their activities and products enabling them to freely engage with communities outside of profit-oriented constraints.

CA were one such workshop who received funding for their production, exhibition and training activities. Channel 4's support of the workshop sector was undoubtedly successful in harbouring aesthetically challenging and culturally diverse productions (Perry 2020; Robson 2020). However, in tracing the interaction of CA and Channel 4, this article emphasises Channel 4's role in depoliticising the radical film practices of 1970s collectives.

CA was formed in 1968. During the revolutionary upsurge of May '68, the French government deported early members Ann Guedes and Schlacke Lamche (Guedes 2020). Upon arriving in England, Ann felt that people were "sleepwalking" (Guedes 2013, p.65) and knew little of the radical events in France. With hopes of disturbing this slumber, she acquired a French student film that documented factory and university occupations. She began to screen the film at trade union branches and shop steward meetings and, thus, CA was born.

Though starting as a mobile cinema, CA quickly began to produce short documentary films in support of key working-class and trade union struggles such as the Upper-Clyde Shipbuilders' (UCS) work-in, the campaign against the Industrial Relations Bill and the miner's strikes of 1974. Importantly, CA worked with collectively owned means of production in close consultation with their films' subjects. Shop steward committee and activists would often invite CA to produce a film on their struggles and contribute to the content and form of films through discussions with the collective.

Early CA films frequently featured solely sync-sound or speeches overlaid on images of demonstrations, picket lines and workplaces. Broadly, such films can be described as 'campaign' or 'agitprop' films in that they are primarily concerned with presenting workers' political line as calls for solidarity and action by others. CA films then serve as intervention in an ongoing struggle. As such, they reflect an aesthetics of 'roughness'; their shots are shaky, out of focus or poorly exposed and their sound is often distorted and unclear. This aesthetic imperfection is a feature of what Chris Robé and Stephen Charbonneau (2020) call InsUrgent Media. Like other forms of InsUrgent Media, the necessity of urgent intervention in an ongoing campaign and lack of resources shaped the roughness of CA's earlier work. As Robé and Charbonneau claim, "the urgency of the material conditions that produce activist films … are reflected in their aesthetics" (Robé & Charbonneau 2020, p.2). Indeed, Pauline Swindells, an early CA member, suggests "content was more important … than form" (2020).

CA screened their own films in order to take them directly to working-class audiences. Screenings took place across working-class spaces and developed through an informal network of shop steward knowledge (Guedes 2020). Screening locations include union branches, factory canteens, building sites, miner's holiday camps, youth clubs, student film clubs, squats and schools. Furthermore, films were often screened in the places in which they were made; for example, Dave Douglass, a trade unionist and collaborator of CA, recollects a screening of CA's UCS1 (1971), their short on the UCS work-in, for the workers at the shipyard. Such screenings did not involve simply showing a film. Instead, screenings were used to engender debate and discussion about the film, its content and how it might inform political action.

With CA's exhibition practice, the straightforward political line of each film was often superseded by collectively formulated and heterogenous responses to the text within post-screening debates. In discussing UCS1, Douglass suggests that the film omits diverse political lines about the organisation of the Upper Clyde work-in but through screenings "these arguments came out anyway" (1999, p.271). CA films became a site of contestation in which both reactionary and progressive political differences and unities emerged. Here, as David Glyn and Paul Marris suggest (1976), a collective audience reading is concrete in its function of aiding groups to determine the collective action they might take. For example, Steve Sprung (2022), an early CA member, recalls a screening in which workers at a Coventry factory were voting on whether or not to occupy their factory. CA showed UCS1 to serve as an example of a previous work-in success for the Coventry workers to debate. The workers subsequently voted to occupy. Sprung's story suggests the CA screening was successful in contributing to the direction and knowledge of potential action. Screenings also helped build material solidarity; on a CA promotional leaflet, a quote from an Upper Clyde Shipyard convenor suggests screenings were used to raise money for strike funds.

CA's collaboration with workers and their itinerant exhibition practices brought their filmic work into the direct service of working-class political movements. CA used the medium and their practices to engender solidarity, class-consciousness and material support for socialist political struggle. However, as the trade union movement declined and funding streams increased through Channel 4 and the BFI, CA's productions and exhibition modes shifted.

At the end of the 1970s, CA's filmic output slowed. No longer addressing immediate and urgent issues and enabled by increased funding support, their films were longer and more reflective. For example, Channel 4 funded CA's first feature-length fiction film Rocinante (1986), which follows an enigmatic nomad as he travels England. With Rocinante, CA's direct connection to and service of the workers' movement all but disappears in the making of the film. Indeed, as was the case elsewhere, the film was not instigated by workers or made to support a specific campaign. Instead, Ann suggests the ideas for the film emerged out of her interest in pastoral poetry (Guedes 2020).

Moreover, whilst Ann asserts that Rocinante was made in a collectivist manner, the presence of individual credits for roles suggests CA's move away from absolute collectivist approaches in favour of more traditional divisions of labour. CA's impetus to work collectively was determined as much by material necessity as it was ideological. When working with limited resources, working together enabled an efficient pooling of resources. However, with the arrival of Channel 4 funding the possibility of realising individual's project ideas emerged. As Pascale Lamche, another CA member, puts it, "the group began to drift apart as individual members sought their own individual ways and production" and collective commitments were hard to maintain "around forms of production that required an entirely different set of priorities (i.e. feature films require an identifiable director, good marketing and exhibition strategies etc.)" (Lamche 1999, p.282).

As CA's production shifted to more reflective modes and fictional works so too did their dominant exhibition mode change. Indeed, later films like So That You Can Live (1981), Rocinante (1986) and Bearskin (1989) were shown almost exclusively in cinemas or on Channel 4. Notably, So That You Can Live premiered at London Film Festival and opened the independent programme Eleventh Hour on Channel Four in November 1982. As the union movement declined, resulting in decreased support for CA from workers and fewer potential screening spaces, and the independent sector gained greater power, resulting in greater funding for CA films and further television slots, this shift to more 'traditional' exhibition modes registers as a response to the changing material conditions.

In offering an immediate and straightforward outlet for exhibition, Channel Four detached CA films from sites of working-class struggle. Where they had previously screened in factory canteens, workers' camps and union meetings, CA films were later seen on Britain's television screens. Although only a small scrap of evidence, many of the unionists I spoke to as part of my research expressed disinterest in watching CA films on Channel 4 suggesting the channel's insignificance for CA's traditional base. As Rod Stoneman, former deputy commissioning editor of Channel 4 independent film and video, suggests Channel 4 "dissolved away" the interconnections across production, distribution and exhibition (2022). With this, CA's ability to specify their audiences also dissolved; Channel 4 broadcasts were unable to directly address the industrial working-class at the point of struggle. CA's use of screening space to engender debate, strategizing and monetary funding was itself negated by Channel 4's public transmissions.

Channel 4 and the Workshop Declaration enabled regular commissioning of work from independents and more substantial funding for workshops (Holdsworth 2017). However, whilst grant-aided and commissioned resources for groups like CA increased, the influx of resources made workshops' operations increasingly dependent on grants. Over the 1980s, as funding declined and Channel 4 shifted to commissioned content, commercially competitive groups were able pushed those non-profit and politically-oriented groups, like CA, out of existence (Holdsworth 2017). The results, as summarised by both filmmaker Margaret Dickinson and Stoneman, were the independent sector "shedding its oppositional connotations and acquiring a purely commercial significance" (Dickinson 1999, p.76) eventually consisting of a "profusion of small businesses" (Stoneman 1992, p.140).

We can draw a useful analogy here. In Volume I of Capital, Marx details the fight for the ten-hour day in Britain and British capitalists' opposition to new legislation. Despite heavy political resistance, the victory of a ten-hour day forced capital to raise "the productivity of the worker" to enable "him to produce more in a given time with the same expenditure of labour" (Marx 1990, p.534) through concomitant technological and managerial advancements. For Stuart Hall, this process illustrates how capital is constantly "forced to weave together its own contradictory impulses into forms of social and economic organisation which it can bend and force to advance its own 'logic'" (2021, p.109). Not all business keeps up with these productive advances and thus the standardised workday "hastens on the general conversion of numerous isolated industries into a few combined industries … it therefore accelerates the concentration of capital" (Marx 1990, p.635).

The historical movement of the British independent sector, that operated on an "agreement to disagree" (Blanchard & Harvey 1983, p.234) in its need for self-sustainment, mirrors the contradictory development of capital in Marx's analysis. In its fight for better resources and working-conditions the sector forced the capitalist state into new advances; Channel 4 granted resources for independents but also accelerated 'free' competition. The increasing dependency on such resources then concentrated capital into larger corporations like Channel 4. When such support was revoked, the radical groups were cut out leaving only those commercial businesses able to sustain their own economic growth. Radical film's contradictory dependence on capital enables capital to recuperate its very oppositionality. Ultimately, despite its radical approach and its extra-commercial operations, CA was not free of the pressures of the market - a fact which registers both at its demise and across its shifts in practices to accommodate industrial changes. The history of CA and Channel 4 then is as much one of working-class resistance as it is a history of capital's ability to, as Hall puts it, "contain within its framework those 'particular' advances which the working class is able to force upon it" (2021, p.109).

About the Author

Ollie Dixon is an outgoing graduate of the MA Film and Television Studies at the University of Bristol. Ollie's research focuses on the history of radical film collectives in Britain and the politics of digital exhibition. His MA dissertation collected original oral histories and archival materials on the film collective Cinema Action to write a comprehensive account of their history. He is currently preparing applications for a PhD project which compares the spatial and temporal experiences of radical film collective across three eras (1930s, 1970s and 2010s) in Britain. He has presented papers at the Radical Film Network's conference in Genoa, Italy and has published work in cultural publications like HERO Magazine. He also holds a first class BASc degree from University College London.

Works Cited

BLANCHARD, S. and HARVEY, S., 1983. The Post-war Independent Cinema – Structure and Organisation. In J. Curran and V. Porters (eds.) British Cinema History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, pp.226-241.

DICKINSON, M. (ed.), 1999. Rogue Reels: Oppositional Film in Britain, 1945-90. London: BFI.

DOUGLASS, D., 1999. Cinema Action Oral History. Interview By Margaret Dickinson. In M. Dickinson (ed.) Rogue Reels: Oppositional Film in Britain, 1945-1990. London: BFI, pp.263-288.

GLYN, D. and MARRIS, P., 1976. Seven Years of Cinema Action. Afterimage, 6, pp.64-83.

GUEDES, A., 2013. Interview by Petra Bauer and Dan Kidner. In P. Bauer and D. Kidner (eds.) Working Together: Notes on British Film Collectives in the 1970s. Southend-on-Sea: Focal Point Gallery, pp. 65-69.

GUEDES, A., 2020. Interview by Chris Reeves. [Online] Available from: https://vimeo.com/422166846.

HALL, S., 2021. The "Political" and the "Economic" in Marx's Theory of Classes. In G. McLennan (ed.) Selected Writings on Marxism. Durham: Duke University Press, pp.91-133.

HOLDSWORTH, C. M., 2017. The Workshop Declaration: Independents and Organised Labour. In S, Clayton and L, Mulvery (eds.) Other Cinemas: Politics, Culture and Experimental Film in the 1970s. London: I.B. Tauris and Co, pp.307-312.

LAMCHE, P., 1999. Cinema Action Oral History. Interview By Margaret Dickinson. In M. Dickinson (ed.) Rogue Reels: Oppositional Film in Britain, 1945-1990. London: BFI, pp.263-288.

MARX, K., 1990. Capital Volume I. London: Penguin Classics.

PERRY, C., 2020. Radical Mainstream: Independent Film, Video and Television in Britain, 1974-90. Bristol: Intellect Books.

ROBÉ, C. and CHARBONNEAU, S., 2020. Introduction: InsUrgent Projections. In C. Robé and S. Charbonneau (eds.) InsUrgent Media From the Front. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.1-20.

ROBSON, A., 2020. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Utopia–The Workshop Declaration (1982–1989). In S, Presence, M. Wayne and J. Newsinger (eds.) Contemporary Radical Film Culture: Networks, Organisations and Activists. London: Routledge, pp.137-147.

SPRUNG, S., 2022. Interview by Oliver Dixon [Zoom call]. 7 July.

STONEMAN, R., 1992. Sins of Commission. Screen, 33(2), pp.127-144.

STONEMAN, R., 2022. Interview by Oliver Dixon [Zoom call]. 18 July.

SWINDELLS, P., 2020. Interview by Chris Reeves. [Online] Available from: https://vimeo.com/421664519.