by Jennifer Good

I have taught ‘history and theory’ to photojournalism and documentary photography students at a central London art and design university for the past ten years. In this setting, I’ve become increasingly aware that as a subject area, photography has a unique level of responsibility to engage with the current sector-wide decolonizing agenda that has finally begun to touch all areas of British higher education. Its particular history – dominated by the colonial gaze and operating within a framework of supposed ‘objectivity’, indexicality and transparency – means that the auditing of reading lists and diversification of the curriculum are not enough: every student and practitioner working within the discipline faces their own reckoning with the camera as an apparatus of colonial violence.

Every year, with each new group of first year students, I introduce historical photographs of colonial oppression: images of people in chains, or forcibly posed within pseudo-scientific schemas designed to demonstrate racial inferiority, or upheld as cultural novelties and sexualized objects of exotic fascination. Almost all of these photographs are of people of colour in the global south who have been subjected to the dominant gaze of a white European photographer. They not only record violence; they enact it in themselves as objects (which is why they must be introduced into the classroom with care), through the sheer force of their supposed authority and objectivity. In these photographs, the direct implication of photography within the apparatus of colonialism is overtly visible.

Then, I show more recent photographs, by celebrated documentary photographers who are some of the industry’s biggest names; people who would never identify themselves with the explicit violence of actual colonial-era photography, but who carry its inheritance in a subtler form – most pervasively, by means of the ‘exotic’. The treatment of indigenous people and people of colour as exotic – mysterious, beguiling, elusive, other-worldly – remains as the most dominant socially-accepted vestige of colonial photography. It is still tacitly endorsed by the photojournalism and documentary photography industries, widely celebrated and enthusiastically consumed by white people the world over. As a result, is also a trope of representation that is continually aspired to by photography students.

Talking Back book jacket

In her book Talking Back (1989), bell hooks goes to the heart of the problem that arises when photographers (or writers) claim to ‘give voice to the voiceless’ or to ‘speak on behalf of’ the oppressed – which is what many photojournalists and documentary photographers have expressly done, and continue to do: “No need to hear your voice when I can talk about you better than you can speak about yourself...Only tell me about your pain…And then I will tell it back to you in a new way …it has become mine, my own.” This is a kind of appropriation and othering that has been the the bread-and-butter of much of the photojournalism industry. Many of these kinds of photographs are made by practitioners that my students, at the outset, admire and may even cite as their inspiration to follow a career in this field in the first place. My job, year after year, is to problematize them. To introduce critical ideas about exploitation, voyeurism, stereotyping, exoticism and the colonial gaze. I often find that I need to do this in very basic, introductory terms, to young, mostly white, students who have never been required to have conversations about privilege before. I need to do it carefully, and with my own institutional power very much in mind. These can be emotive conversations – students questioning their own work, work they have revered, even the whole premise of the photojournalism industry as it currently operates.

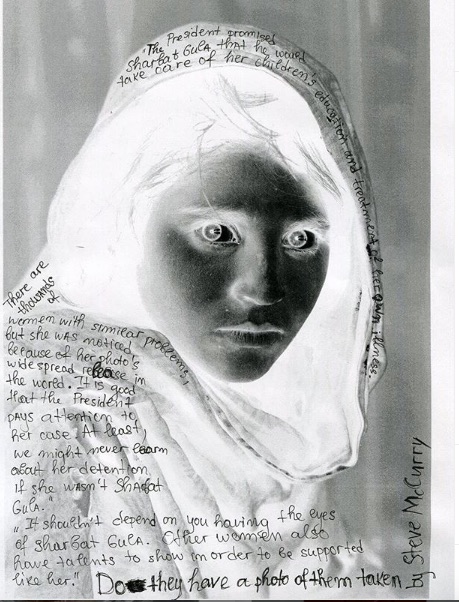

Artwork by Bayryam Bayryamali, with permission

Critic and artist Martha Rosler is perhaps the most famous and most forceful voice of an era in the late 1980s when the critique of this kind of othering was at its height. Her essay, ‘In, Around and Afterthoughts on Documentary Photography’ (1981) is so profoundly critical and negative in its assessment of the genre that I set it regularly as required reading for students. It usually provokes a strong reaction, which is a useful thing in the classroom. But the position of Rosler and others became so influential at that time, that it resulted for several years in a kind of representational paralysis: there are inherent problems with representing otherness, suffering and inequality, so much so, that it seemed to many that photography couldn’t win. But does that mean that it shouldn’t try at all?

This is the dilemma faced by my students and I. Strong feelings can arise when students’ (and teachers') own direct or indirect implication in these legacies of oppression are confronted. In the words of one student, ‘the safest way to not misrepresent anybody is to never take any photos again.’ I have heard students confess that these questions keep them awake at night, wrestling with guilt, disillusionment, defensiveness and anxiety. As one student anonymously told me, ‘I feel really frustrated and overwhelmed because I wish I’d started thinking about this, or that I knew about the problem of representation before I started taking photographs, because now I feel like I’m part of the problem…It’s kind of culturally engrained in us to think and represent in a certain way. And now I feel overwhelmed because I have to think more critically.’ This response is often nothing more than a very specific form of the ‘white fragility’ written about by Robin DiAngelo (2018), Reni Eddo-Lodge (2017) and others – the idea that the hurt and defensiveness of white people is so often centred within conversations about race at the expense of the people of colour who are the actual victims of racism. But it also constitutes a kind of creative ‘stuckness’ that has very practical implications within the educational setting.

Short of quitting their course, these students have no choice but to continue taking pictures – that is what they have come to university to do. So what then? A journey begins, in which students must confront the politics of representation and privilege as potentially worldview-altering concepts, confronting difficult feelings in the process, and working towards a more conscious and progressive kind of practice. As a teacher, I’m interested in exploring these feelings not just for their own sake, but because they have a direct impact on students’ practice, or at least their attitude to their practice. How can they be navigated in a way that is mindful of students’ holistic wellbeing, and yet does not concede to white fragility or shy away from our collective responsibility to confront histories of oppression?

In their very influential pedagogic research, Jan Meyer and Ray Land propose that all disciplines within education contain ‘threshold concepts’ – key, foundational concepts that bring with them a ‘transformed way of understanding, interpreting, or viewing something without which the learner finds it difficult to progress, within the curriculum as formulated’. These concepts can be extremely ‘troublesome’, not only to grasp in the first instance, but in their subsequent integration within a students’ ongoing practice. The transformation that can be involved in this process has been likened to an awakening from innocence, which accounts very well for the process that students on our course often experience in encountering questions of representation and power. One of the most important characteristics of a threshold concept is that once acquired, there is no going back. In Meyer and Land’s words, ‘As we gain new knowledge, we are changed by it, and these shifts are manifested in a changed use of language.’ Transformation takes place as the student moves into a new space of critical consciousness, and new identities are formed.

I recently got in touch with a group of last year’s graduates of our BA course, asking them to look back and share with me their reflections on the process of wrestling with these concepts (of colonialism, power relations and representation in photography).* Bayryam told me that he identified straight away with what I have called ‘critical paralysis’. For him, it meant ‘understanding that I have to unlearn common ways of looking, shooting and representing…and that process takes time.’ This ‘unlearning’ – and the time that it takes – is a common thread that runs through decolonizing efforts of all kinds across the university. It is a point at which the priorities of decolonizing and the priorities of education itself – conceived of as an essentially liberatory, consciousness-raising practice – intersect and become inseparable. As a threshold concept, the decolonizing of photography is ‘troublesome’, fraught with emotion and discomfort, precisely because it is transformative. Bayryam went on to stress that this process, as difficult as it is, ‘has developed my work immensely…I think that critical paralysis should not be solely considered as a problem but cherished in an educational setting. We should celebrate that students are questioning their practice and make them feel good about the uncertainty that they feel about the way they represent. This means that they care, and caring is a laborious and emotional task which does not have to be easy.’

Pioneering educational thinkers including hooks, Paulo Freire and Stephen Brookfield have long argued for a pedagogy that welcomes both student and teacher into the classroom as a whole person, fully including each individual’s emotions, hopes, fears and history as well as just their ‘mind’, as if this existed in an intellectual vacuum. This is hard to do, and makes both teaching and learning a continual process of vulnerability as well as intellectual rigour. At times, this approach is hugely rewarding. At others, it’s exhausting – especially when we recognize that critical paralysis in relation to the work of decoloniality can be an even greater stumbling block for teachers than for learners. Another former student, Tom, said that the key thing is for each person to ‘identify their own privilege, what role they play…and to discuss with each other how to overcome this.’ The goal of this collaborative self-reflective process is to find other, better forms of representation that become part of the solution rather than part of the problem. My own whiteness at times causes me to shrink from the work of telling colonial histories that are not mine to tell except from the point of view of the colonizer. I carry this power, as well as the power of the teacher within the apparatus of higher education.

Both must be reckoned with, so that the classroom becomes a site of mutual and collaborative openness, resistance and freedom, as well as of ‘trouble’, which is just the other side of the same coin.

About the Author:

Jennifer Good is a writer and Senior lecturer in History and Theory of Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. She is the author of Photography and September 11th: Spectacle, Memory, Trauma (Bloomsbury 2015), co-author of Understanding Photojournalism (Bloomsbury 2017), co-editor of Mythologizing the Vietnam War: Visual Culture and Mediated Memory (CSP 2014) and writes regularly for photography magazines and journals. As well as photography, conflict, psychoanalysis and memory, her research interests also include pedagogies of reading, writing and power

*Thank you to Bayryam Bayryamali and Tom Barlow Brown