by Elisabetta Garletti

Watch the ViewFinder BoB Playlist for this essay

As the current pandemic has transformed our sense of home with feelings of entrapment and isolation, Jamie Crewe’s film Ashley (2020), premiered only a few weeks before the UK went into lockdown, speaks almost prophetically to the anxiety that has come to define our relationship with the domestic sphere in the past months. Ashley is the first stand-alone, cinematic work by the Glasgow-based artist, whose videos often form part of multi-media exhibition projects. Ashley was realised with a commission Crewe received as the recipient of the 2019/20 Margaret Tait Award, the most prestigious Scottish moving image prize awarded to artists for experimental and innovative work. Crewe described the 45-minute film as an ‘isolated film about isolation,’ which follows a single character played by the artist, Ashley, while they are spending a weekend away in a remote cottage in the Scottish countryside (1).

We learn that they have travelled there to recover from a period of depression, triggered by heartbreak and a divided sense of self. Soon, the quiet and idyllic shelter turns into a nightmarish setting, as mysterious external – or perhaps internal – forces begin to threaten Ashley’s safety. Crewe’s film, drawing from the conventions of the rural and domestic horror genres, toys with the notions of ‘home,’ conventionally a signifier of safety and familiarity, and publicness, in order to explore the complexities of trans-femininity and the struggle with self-acceptance and representation. These themes are mainly explored through the protagonist’s relationship to space: the space of their body, characterised by a shifting sense of identification and disconnect, but also the private space of the home, defined by a double-bind of safety and self-isolation, and an often unwelcoming and dangerous public space that must however be reclaimed by those who are often excluded from it.

Jamie Crewe, Ashley (2020), video still. Courtesy of the artist.

The beginning of Ashley will titillate the sadistic desires of the ‘cabin-in-the-woods’ horror fans. As the scarlet red background of the title card fades, the hand-held camera follows Ashley, their back turned against the viewer, dragging a wheelie case behind them and walking further away from the spectator. The shaky camera gets intrudingly closer to Ashley: we see a close-up of their long, mahogany hair arranged on the top of their head by a hair clip, but their face remains concealed to us. Only after we are revealed their destination, an isolated, white-walled cottage by the coast, we encounter Ashley’s face. A satisfied smile appears on their lips as the voiceover announces: ‘Here I was. My home for the weekend. I marvelled at the place.’ We follow Ashley as they go inside and familiarise themselves with their new home, and the voiceover continues: ‘What a gift! Back in the countryside, alone in the quiet.’

A viewer versed in the horror genre will probably smile at Ashley’s naivety, knowing that loneliness and quietness are always a dangerous pairing. Throughout the course of the film, howling sounds suggest the presence of something, or someone, threatening Ashley’s safety, however, this presence remains unknown. They have the feeling that someone visits them at night, they wake up feeling bruised, but have no recollection of who might have assaulted them. After a swim in the sea, blood starts mysteriously trickling down one of Ashley’s legs, but they are unaware of who or what might have cut them. In a climactic moment, during a walk in the forest, Ashley’s sight gets inexplicably blurred and, as they tentatively find their way back to the cottage, we sense that something is following them, but neither Ashley nor the spectator can see what it is.

The recent years have witnessed a renewed interest in the domestic horror genre, with a wealth of productions that have returned to the home as the central source of terror, from films that exploit our fears of entrapment and home invasion, such as Get Out (2017) and A Quiet Place (2018), to the haunted house of Ari Aster’s directorial debut Hereditary (2018). There is something primal to the fear that home, the epitome of safety and comfort, can be violated or that it might itself constitute a danger, a phobia that the horror genre has cunningly capitalised on for decades.

Haunted houses, home invasion, remote cabins in the woods, possessed bodies of family members, murderous mothers and monstrous pregnancies, are only some of the tropes that have populated horror classics – think of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) or The Shining (1980) – revealing how often the most fearful fantasies are those that threaten our sense of the familial and familiar. A present resurgence of interest in the domestic horror genre is no coincidence in a time when borders are being tightened, right-wing parties thrive on xenophobic and anti-immigration sentiments, and a neo-conservative discourse is expressing a fear over the ‘attack’ of contemporary gender politics against ‘traditional’ family values. It is no novelty that horror films are often reflective of the prejudices influencing the social and collective unconscious of their time, be them racial, gendered, or linked to ideas of disability and illness. Fear of otherness viewed as the deviation from ‘the norm’ has often informed the fashioning of monsters and antagonists in horror. Crewe’s film resorts to the domestic horror genre to confront contemporary fears of otherness in relation to gender expression.

Jamie Crewe, Ashley (2020), video still. Courtesy of the artist.

Ashley brings a breath of fresh air to the stultified portrayal of femininity and gender non-conformity in mainstream horror, where female, queer and transgender characters are often relegated to flat, archetypal roles, the products of an underlying conservative, misogynistic and transphobic imaginary that begets them. Women in the horror genre mainly appear as victims or monsters. They are either relegated to the passive role of prey to an active, male perpetrator – a trope that satisfies the sadistic fantasies of a distinctively male audience – or the material and reproductive functions of their bodies are framed as threatening and monstrous, something that also furthers a problematic equation of gender with the biological body. In her seminal book The Monstrous-Feminine (1991), Australian scholar Barbara Creed analysed the wealth of motifs that cast femininity as abject in horror films (2). Monstrous wombs, possessed women, castrating mothers, the vagina dentata, are all tropes that arise from a fearful perception of the female body. For the realisation of Ashley, Crewe explained that they were inspired by the British tradition of rural horror film and TV, by films such as Robin Redbreast (1970) and ‘The Visitor’ from West Country Tales (1982), which also explore fears related to what are conventionally thought of as ‘female experiences,’ such as motherhood and pregnancy, within a frightening domestic setting (3). Crewe’s film speaks to this tradition, but adapts it to a contemporary, and more inclusive, understanding on gender, choosing to have a trans-feminine character as their protagonist.

In Ashley, gender identity is no longer treated as a defining attribute that confines the character to an established role, nor it perpetuates the problematic equation of gender with the biological body. Ashley’s gender expression is fluid and unfixed, it emerges progressively through the character’s psychology and remains undetermined, challenging conventional binaries that have long defined gender positioning in horror. Crewe’s film also sets up against the spectacularisation and caricaturing of trans or trans-coded bodies in the horror genre. Trans and queer characters are often assigned the roles of attackers, monsters or predators, with gender non-conformity being problematically framed as a symptom or as the cause of their murderous insanity. The unexpected gender reveal of cross-dressing characters has become a recurrent motif in horror to provide a final shocker or plot twist, a tradition inaugurated by Psycho (1960), and continued in films such as Homicidal (1961) and Terror Train (1980).

Explicitly trans characters have emerged in the 1980s and 1990s in films such as Dressed to Kill (1980), Fatal Games (1984) and Silence of the Lambs (1991), where transness, however, is problematically singularly addressed as a sign of the killers’ mental instability. This narrow and caricatural portrayal encourages a transphobic narrative that pathologises transness, portraying it as ‘unnatural’ and casting it as a threat to what is perceived as the ‘normative’ conception of gender identity. Against the superficial objectification and abjectification of trans bodies in mainstream horror, Crewe’s film provides a more intimate and complex portrayal of trans experience, where gender is addressed in relation to the character’s own sense of embodiment, and their ambivalent positioning within the domestic and public spheres.

Jamie Crewe, Ashley (2020), video still. Courtesy of the artist.

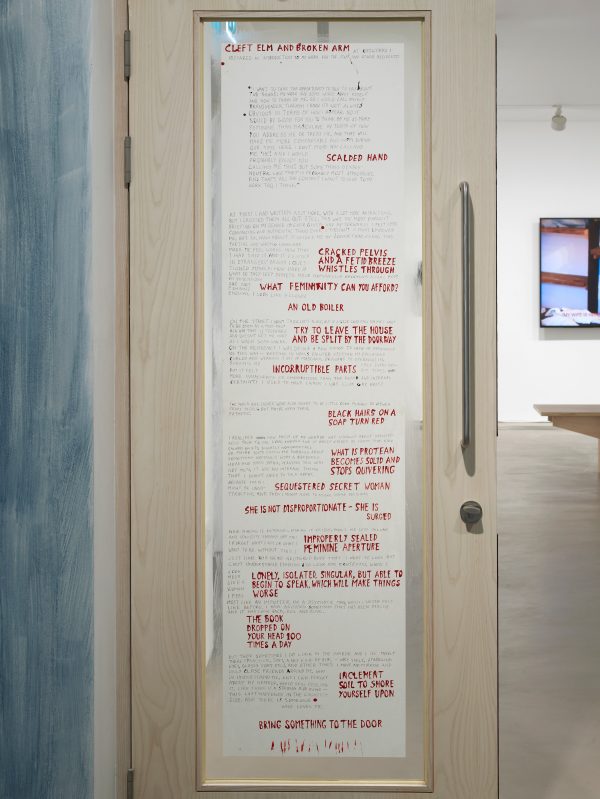

The trans body is the central element in Ashley, a body that is constantly surveilled by the camera and intrusively examined through extreme close-up shots. Crewe explained that the over-exposure of the trans body in the film was a deliberate choice, intended to explore the violence and ethics of representation, a longstanding interest in their artistic practice, something they also explored in earlier works such as Stone Breaker (2017). This textual work could be understood as a companion piece to Ashley, and deals with Crewe’s own ambivalent feelings towards the open manifestation of their gender identity – whether visual or verbal – and what they feel is an insurmountable disconnect between their own sense of embodiment and public perception. Contrary to the horror genre’s focus on the exterior surface of the trans body as monstrous and menacing, Ashley’s gender expression is intimately addressed: we get access to their thoughts through the voice-over that narrates Ashley’s interior monologue, which conveys a sense of vulnerability and Ashley’s own struggle with self- and public perception.

In a key scene, Ashley stares at their reflection in the kitchen window: they smooth their hair, they pose lifting their chin up, they pull on the hoop earrings on their ears. The voiceover utters: ‘From certain angles I looked correct. From certain angles I looked like I used to look.’ The comment invites us to think about what ‘correct’ representation might be, and what often is left out of representation in the name of ‘correctness.’ In a later scene, while Ashley is taking a walk in the forest, we hear them wonder: ‘What even was I? A lump. A shapeless, neutered body, ineligible for love or sex. What else could I live on?’ The external voice seems to assume an autonomous role: are we hearing Ashley’s thoughts or are the thoughts projecting an external judgement onto Ashley’s body? This is further complicated as we discover in the credits that the voice-over is recited by a different actor, Crewe’s friend and long-term collaborator Travis Alabanza, leaving us to question whether the voice that we have been hearing all along was Ashley’s or whether they were trapped in a narrative that is not their own.

Jamie Crewe, Stone Breaker (2017), knife-drawn text on paper. Photograph by Andy Keate. Courtesy of the artist and Gasworks, London.

Contrary to the conventional framing of the transgender character as the killer, Ashley is the victim of a mysterious perpetrator. Assault on their body is signalled by mysterious symptoms: they wake up feeling bruised, they bleed, they temporarily lose their sight, but they have no recollection of who or what might have caused them. This presence is only hinted by howling sounds humming in the background, and by the subjective camera eye surveiling Ashely at all times without them noticing, suggesting that a furtive presence is constantly looming over them. Who is the enemy in Ashley? In one of the final sequences of the film, as Ashley anxiously prepares to go outside and face their attacker, we hear them thinking: ‘I knew it was there! It was on the rocks, in the trees, in the water, in the villas and bungalows, behind the tinted car windows! Something which didn’t want to be seen, but wanted to watch. Something which had an appetite for me.’ They open the door in an impetus of bravery, the blinding daylight flashes through the open door, but an abrupt jump cut brings us back into the darkness of the house where Ashley is still waiting behind the closed-door, as if they never left or perhaps were prevented to leave.

Both the domestic and external space are rendered unsafe and inhospitable by this haunting presence and Ashley’s final remarks cannot help but make us wonder whether we – the spectators – have been the threat pursuing them all along. Hidden away in our seats in the darkened cinema theatre, we have been secretly savouring Ashley’s fear, consuming their body and listening to their innermost thoughts, regardless of their consent. This self-reflexive turn in Crewe’s film ultimately invites us to reflect on the implicit violence that can be inflicted by uncritical representational and viewing practices, practices that often contribute to the marginalisation and discrimination of vulnerable bodies. A challenge to the mindless spectacularisation and objectification of trans bodies in mainstream horror, Crewe’s Ashley leads the way to a more diverse, intimate and complex portrayal of trans experience, something that might inaugurate a new exciting chapter for transgender horror.

(1) Johanna Hedva, “Four Artists to Watch in 2020,” frieze, December 2019. https://www.frieze.com/article/four-artists-watch-2020

(2) Barbara Creed, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1991)

(3) “Jamie Crewe on Publicness and Filmmaking,” SQUIFF, September 2020. http://www.sqiff.org/news/jamie-crewe-on-publicness-and-filmmaking/

Find out more about Jamie Crewe's Ashley here: https://lux.org.uk/event/jamiecrewe-ashley

About the Author

Elisabetta Garletti is a PhD candidate in the Department of History of Art at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on gender representation in contemporary British moving image art, with a particular interest in how representation of 'femininity' is reconfigured in response to queer, post-feminist and posthuman discourses.