This is an ‘interim report’ by Dr Sheldon Hall, Sheffield Hallam University, on his long-term project on the history of the showing of feature films on British television, covering virtually the entire history of broadcast television from the 1930s to the present. Here he focuses on the 1970s.

About the Author: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It – The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). He is currently writing Armchair Cinema: Feature Films on British Television for publication in 2016.

About the Author: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It – The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). He is currently writing Armchair Cinema: Feature Films on British Television for publication in 2016.

NB: A shorter version of this article was first published in the June 2015 issue of Viewfinder.

Preamble

This is an ‘interim report’ on a long-term project on the history of the showing of feature films on British television, covering virtually the entire history of broadcast television from the 1930s to the present. Not to mislead you, I will not be proposing an elaborate thesis or developing a complex argument: it is very much a snapshot from work in progress, a summary of selected findings, for whatever interest it might contain – and I would appreciate constructive feedback on the extent to which it is interesting! I will not be attempting even a full account of the ten-year period in my title but will try to give a general survey of the field in the 1970s while focusing on 1975 for most of my examples. The choice of year is not arbitrary: aside from coming at the exact midpoint of the decade and being reasonably representative, it also allows me to focus on a number of key controversies, events and developments affecting the presentation of films on television in subsequent years. It also happens to be the first year in which I, as a viewer, was fully cognisant at the time, having started regularly buying the Radio Times in September 1974 and the TV Times in January 1975, and already compiling lists of films on TV – something I’m still doing!

...the only films available to television for more than two decades were B pictures from minor distributors, foreign-language films and mostly pre-war independent productions...

The Context

Although feature films (made for the cinema) had been shown on the BBC from 1937 and on ITV from shortly after its inception in 1955, UK broadcasters were only given comparatively unrestricted access to the backlogs of the major distributors (British and American) from 1964. The mainstream British film industry – especially exhibitors, as represented by the Cinematograph Exhibitors’ Association (CEA) – had always strongly resisted the showing of any films on television at all. The British branches of the Hollywood majors went along with this, with the result that virtually the only films available to television for more than two decades were B pictures from minor distributors, foreign-language films and mostly pre-war independent productions, some of them originally released by the majors but that had slipped out of their control. Producers and distributors who dealt with the TV companies were threatened with effective blacklisting and their films, past, present and future, being boycotted by cinemas. From the late 1950s, the backlogs of a limited number of companies became available to TV: among them those of the defunct RKO Radio and Ealing Studios along with the pre-1949 films of Warner Bros. But these were exceptions.

This situation changed in late 1964 when the independent Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn and the American company MCA (Music Corporation of America, which as well as owning Universal Pictures also controlled the pre-1949 backlog of Paramount Pictures) sold large packages of films to ITV and the BBC, respectively. This broke the blockade. The CEA conceded that films more than five years old could be sold to television without objection (features not actually released in the UK could be sold and broadcast freely). The networks now had access to an estimated 9,000 films, allowing them to pick and choose from the offerings of the majors and with no competition but each other.

Over the next few years a great many ‘vintage’ as well as relatively recent films were released for the first time to television. But even by the early 1970s the supply of titles considered suitable for TV was running out and by the end of the decade most of those shown on all three channels were reruns; the bulk of those older films that remained unscreened were regarded as too dated or too minor to be worth reviving and many of the newer films were unacceptable for a family (or even adult) audience. So although the number of films transmitted increased more-or-less year on year, the number of premieres declined in both real and relative terms and, from 1972 onwards on the BBC, was significantly exceeded by the number and proportion that were repeat showings. From about that time onwards also, the BBC and ITV acquired and screened an increasing number of films that had already been shown by the rival channel in order to increase the supply of suitable product.

The need to acquire films when they became available was dictated partly by competition... and partly by the need to accumulate increasingly scarce resources...

The Constraints

Aside from the CEA-imposed ‘five-year’ rule (which the broadcasters were loath to accept although in most circumstances they had little choice but to do so) the BBC and ITV operated within a number of other constraints, some of them self-imposed. I’m drawing here particularly on documents internal to the BBC (especially a report on stock policy prepared in 1972) and the Independent Broadcasting Authority (the IBA).

It was BBC policy to acquire all those suitable films that were available to it, subject to limits on the maximum value of the stock (not to exceed more than about £5 million) and with the proviso that at any one time the number of films available for first transmission should not exceed 450 – reckoned to be about two years’ supply, though in fact by the end of the decade it was equivalent to more than three years’ worth. The need to acquire films when they became available was dictated partly by competition – if the Corporation didn’t buy them, ITV would – and partly by the need to accumulate increasingly scarce resources (especially where premieres were concerned). Films were purchased – or rather, leased for a fixed period and usually for a specified number of screenings (typically three or four times over five or seven years, though this could vary even among the films in a single package) – by a team led by Gunnar Rugheimer, Head of Purchased Programmes, a Canadian and a notoriously combative personality. Members of this team also helped with scheduling or ‘placing’ the films, though the Controllers of BBC1 and BBC2 had ultimate say over which films appeared in which slots. The BBC imposed an approximate limit of 12% on the proportion of its output devoted to ‘foreign’ (including American) programming. This included acquired series as well as films, so the number of features that could be screened was controlled partly by the number of bought-in series that were transmitted. Typically throughout the 1970s an average six to eight films were shown in a normal week (more in holidays), divided between the two channels, with BBC1 showing slightly more than BBC2 until 1979, when the balance shifted the other way.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Stricter controls were imposed on ITV, partly by its regulatory body, the IBA, and partly by various agreements with the showbusiness talent and craft unions. It is worth emphasising that ITV was not one channel but 15 companies which held the local franchises for 14 regions (London being split between two companies, Thames and London Weekend). Most films were shown on a local basis, with relatively few films fully ‘networked’ (i.e. shown simultaneously across the whole country) or even part-networked (though two or more stations often linked up for the showing of particular films). Films were bought on behalf of the companies by the Network Purchase Group, comprising representatives from the five largest companies and a single representative acting for the remaining nine. But the work of seeking out and negotiating film and series acquisitions was largely done by one person, Granada’s film scheduler Leslie Halliwell, whose proposed deals had to be ratified by the group. Once acquired, films were put into a ‘pool’ that could be drawn upon by each company according to its scheduling needs – and there was considerable variation in the number of films shown by each station. Companies could opt out of particular purchases if they wished, and conversely they could also acquire their own, for local use only – Halliwell did this a good deal for Granada, buying many older films that did not interest schedulers in other regions. Wherever they operated, companies were limited to a maximum number of features weekly (again except for holidays). At the start of the decade this was five, subsequently increased (as broadcasting hours were extended) to six and then seven, of which no more than four per week – averaged across a quarter – could be British. This was to placate the unions, which feared that a reliance on old and already-completed films (and shows) would mean less work for their members. There were also restrictions on how films could be placed in the schedules – two or more were not usually permitted to run consecutively, in order to ensure programme variety – and safeguards on content and age suitability (of which more later).

The Costs

The aforementioned report prepared by Gunnar Rugheimer in 1972 set out the then-current stock situation and the BBC’s present and future film needs. Films were classified in five quality grades, each with an approximate purchase cost:

Specials: £17,700

Grade A: £12,200

Grade B: £8,200

Grade C: £5,900

Re-runs: £2,500

As films were usually bought in packages which varied considerably in size and whose contents did not come with individual price tags, these prices were perhaps notional. Costs had increased significantly over the years: in the early 1950s the BBC expected to pay only around £300 or £400 for particular films, whether bought individually or in small groups. By the mid-60s, with the opening of the majors’ vaults, the average price was around £4,500 to £5,000 per film and packages could include over 100 films bought at a time; one BBC package bought from United Artists in 1974 included over 400 films.

However, average prices increased significantly throughout the 1970s as major premieres became scarcer. Even by 1972, an average film cost £10,000, and this kept on rising. The prices for the really big films could be substantially above the average, as the distributors gradually released to TV the blockbusters that they had previously been keeping back for theatrical rerelease. At the start of the decade the highest price for a single film appears to have been the £18,000 that ITV paid for Oklahoma!, first transmitted on Boxing Day 1971 – ‘specials’ of this kind were usually designated for major holidays and other such occasions. But this was exceeded by the £125,000 paid by the BBC for The Bridge on the River Kwai (premiered Christmas Day 1974) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Christmas Day 1975), £250,000 for Oliver! (Christmas Day 1976) and over £2,000,000 for The Sound of Music (Christmas Day 1978).

https://youtu.be/UY6uw3WpPzY

The BBC was much criticised by the press and the unions for purchases such as these, made at a time when the Corporation was heavily in debt (some £15 million in 1975). But in fact the purchases came about partly as a result of the BBC’s financial straits: however costly they were to acquire, these were still cheaper than the cost per hour of producing original drama (only just in the case of The Sound of Music, which was bought for ten screenings over ten years). This is how their value was calculated by the BBC, along with these films’ considerable power as ratings boosters – the biggest of them drew audiences larger than almost any programmes except the BBC’s most popular shows, such as Morecambe and Wise and The Generation Game (internal and external statements made a point of saying that the BBC was proud that these programmes still commanded the largest audiences rather than bought-in items).

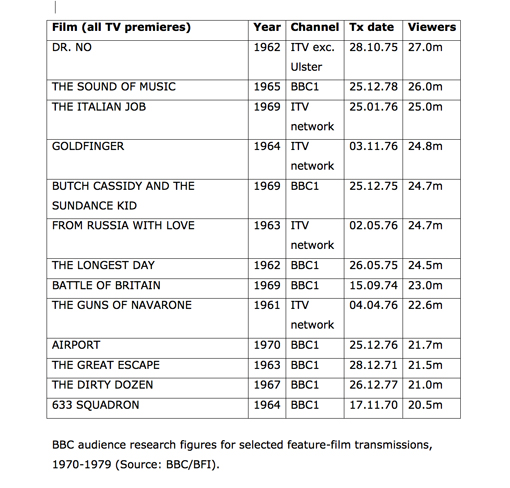

ITV’s most expensive items in the 1970s were the epic Ben-Hur ($800,000 or about £457,000) and the first nine James Bond films, acquired in packages of six and three for £850,000 and £540,545 respectively. Although some big films were premiered on big holiday dates (such as The Robe on Good Friday 1975), others were used strategically in the ratings war, usually in the Autumn and Spring seasons when the broadcasters launched their new series (such as the premiere of Quo Vadis in the first week of September 1975). These purchases too were often criticised, but on different grounds from the BBC’s – as private companies rather than publicly funded broadcasters, they were bought with the network’s own money. They were instead criticised not so much by the press as by the film trade itself, in an echo of the industry’s past attitudes towards television as a rival entertainment medium. The acquisition for TV of the Bond films and other blockbusters was seen as depriving exhibitors of product on which they could make a considerable continuing profit in subsequent runs and reissues. It was reported in the trade press that in 1974 – when the first six Bonds had been acquired by ITV – the first eight Bond films in aggregate had earned enough money that year to be placed as a group among the top ten box-office hits. Not only was the food being taken out of exhibitors’ mouths – that is how it was presented – but it was being thrown back at them when these films were scheduled in peak evening slots and drew audiences away from new films in cinemas. It was claimed that when The Italian Job was TV-premiered on a Sunday evening in January 1976, cinema takings across the country fell by as much as 60%. The major ITV premiere of 1975 was the first James Bond film, Dr No, in October, which according to JICTAR’s ratings drew a record audience for a film on TV to date and, according to the BBC’s own alternative viewing figures, an all-time high one of 27 million people. The BBC’s ratings blockbusters of 1975 were both on Christmas Day: The Wizard of Oz and the ‘world television premiere’ of Butch Cassidy, for which Paul Newman’s personal permission had to be sought. According to the BBC’s ratings (but not JICTAR’s) they drew audiences of 20 and 24.7 million viewers, respectively.

Scheduling Patterns

There were distinct differences in the way the BBC and the ITV companies scheduled their films. All broadcasters typically kept to regular weekly slots, some of which were changed on a seasonal basis (so BBC1’s or BBC2’s midweek film might change from a Tuesday to a Wednesday evening; or an ITV Saturday-night film might change from early evening to late evening). Throughout the decade, it was usually possible for viewers at least in some parts of the country to see a film every night of the week and in some cases to have a choice among several (video recorders not becoming widely available until the late 1970s).

Following a policy introduced by David Attenborough when he had been Controller of BBC2 in the 1960s, the BBC channels generally avoided scheduling films against one another (with the occasional exception when BBC2 was showing a foreign-language film) and instead planned programme ‘junctions’ so that a viewer could, for example, switch over after the end of a film on BBC1 in time to see the start of one on BBC2. On the other hand, certain slots were typically battlegrounds for BBC1 and ITV, notably Saturday and Sunday evenings. The BBC most often used evening slots for premieres, with off-peak slots (especially weekend afternoons) for repeats or occasionally premieres of minor films; the pattern with ITV was less regular, and again subject to variation among the regional companies.

...it was usually possible for viewers at least in some parts of the country to see a film every night of the week and in some cases to have a choice among several...

Besides regular slots, the most common scheduling strategy employed by the BBC was the practice of grouping films in thematically related series or ‘seasons’. In the 1960s such seasons had often been very long indeed, with Saturday-night Westerns and thrillers on BBC1 or weekday-night vintage classics and musicals on BBC2 running for over a year without a break. Seasons in the 1970s tended to be shorter than this – four to eight films were typical, though some could be longer – and were particularly useful for presenting repeats in a way that gave them a certain freshness and coherence, interspersed with an occasional premiere. Typical ‘hooks’ for seasons were stars, genres and directors, but also on occasion other creative figures such as writers and even studios, or a more general theme, such as ‘Images of Childhood’. The BBC’s longest season of 1975 was the chronological sequence of sixteen of the seventeen Tarzan films made by MGM and RKO between 1932 and 1953 (the one omitted being the first, the only one the BBC had shown previously and the least often repeated). Despite their age, many were receiving their UK TV premiere and the others their first screening on the BBC; whereas ITV had tended to show them in holiday afternoon slots, the BBC scheduled them at peak time on Tuesday evenings on BBC1. Also notable was a series of six films made during and about World War Two and showing for the first time on TV in a peak-time Sunday evening slot, hosted by David Niven. Several director seasons were linked to a series of bought-in American interview profiles, The Men Who Made the Movies, which continued in 1976. But perhaps the landmark season of the year was the first series of horror double bills on late Saturday nights during the summer on BBC2 – a novel scheduling idea that became an annual institution for nearly a decade.

ITV companies programmed seasons less often, though it was not uncommon for them to bill film slots under generic rubrics such as ‘Big Star Movie’ or ‘All-Action Western’. Granada practised seasons more than most companies, due to Halliwell’s influence, and some groups of films particularly lent themselves to themed slots, such as the classic Universal horror movies that Halliwell acquired in 1969. But perhaps the most adventurous film series of the 1970s were the occasional Experimental Film Seasons (sometimes billed as ‘Film Club’) programmed by the Welsh station HTV in the summer months, which often showcased foreign-language, documentary and independent films, sometimes of a highly controversial kind. Most other ITV companies showed foreign films, such as spaghetti Westerns and ‘continental’ thrillers, only in dubbed versions.

The Controversies

For the remainder of this paper I want to focus on two sets of controversies that arose in a single year, 1975, both concerning ITV and both illustrating the potential hazards that lay in wait for different kinds of scheduling decisions regarding films aimed at very different sorts of viewer. Both saw the network struggling to accommodate itself to different demands made by quite distinct audience groups.

The first of these was a harbinger of a trend that was to continue throughout the decade and on into the years beyond, and which resulted in a significant increase in the number of viewer complaints reaching the IBA. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the principal complaints regarding films concerned a problem suffered by ITV far more than the BBC: the cutting of films to fit arbitrary time slots (something the BBC claimed never to do). But from the mid-70s these were superseded by related but somewhat different types of complaint: that certain films had been cut too heavily because of adult content; that these films had not been cut enough to remove more adult content; or that they had been shown at all, cuts or no cuts, because of their subject matter. This situation was precipitated due to the nature of the material that was increasingly becoming available to television.

...many films now included material that would have been prohibitive only a few years before: in essence, sex, violence and bad language, and the breaking of social taboos.

Changes in censorship in the 1960s (notably the introduction of an age-graded ratings system in America) as well as the increasing targeting of films at an adult or young-adult audience meant that many films now included material that would have been prohibitive only a few years before: in essence, sex, violence and bad language, and the breaking of social taboos. In cinemas these were most often given ‘X’ or ‘AA’ certificates in the UK and ‘X’ or ‘R’ in the US. When viewers wrote in or called to ask, as they often did, why broadcasters couldn’t show or publicise these ratings when the films were televised, they were invariably met (by both the BBC and the IBA/ITV) with the same responses: that in many cases the ratings were outdated and would no longer be applied to the films by the censors themselves; that publicising such ratings as a warning would act as an attraction to younger viewers rather than a deterrent; and that in any case they were applied by a film-industry body that had nothing to do with the broadcasters.

The ITV system had its own classification system, developed in the late 1960s. Before a newly acquired film could be shown it had to be viewed by a representative of a programme company – usually the first one to show it, though in later years it was argued that the Big Five companies could do this more efficiently and responsibly than the smaller ‘regionals’. It would recommend or make any necessary cuts for content and issue a certificate based on the film’s suitability for broadcast in particular time slots: usually SAT (suitable any time), post-7.30 and post-9.00; in some cases films were recommended as suitable only after 10.30 and in any case the networked News at Ten made scheduling of films at 9.00pm difficult (the IBA did not like films straddling the news, though it often happened). Despite this, the more controversial films often attracted outrage that material which could only be seen in cinemas by adults making a conscious choice to do so was being transmitted into the home where there was no restriction on who was watching and where the unwary might stumble on scenes that they could find upsetting, offensive or corrupting.

In the Autumn of 1975, most of the ITV companies changed their regular early Sunday evening film slot (typically starting at 7.25 or 7.55) for a later one starting at 9.10. The change of hour reflected the more adult nature of the films selected for the slot. None of the films was fully networked but several were part-networked. The IBA expressed the hope that the companies would not schedule the most contentious films on successive weeks but would instead intersperse them with less risky material. Several of the films nevertheless attracted complaints, along with many letters expressing general concern about the number of X- or AA-rated films that were now being shown on TV. Two films in particular received a large number of complaints which continued to come in as the films circulated around the regions: Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and The Killing of Sister George.

The former, a satire on modern American sexual mores and especially sex therapy, culminates in its four titular characters (two married couples) sharing a bed as they experiment with spouse-swapping. It was not only the sexual morality that inspired complaints but also the dialogue. Some comments from letters:

- ‘The film’s sexual frankness was quite offensive, and I cannot see how discussing orgasm or ‘balling a chick’ is suitable entertainment for peak hour family viewing time on a Sunday.’ (Mr JCG, Carlisle)

- ‘I, like others, pay £8 to watch television, and believe me, it’s certainly not to see silly women expose themselves to the public. In case you think I must be a silly old maid, you’d be very wrong, I am only eighteen.’ (Mrs EG, Glasgow)

- ‘The Hallelujah Chorus hardly seems appropriate music to accompany sensuous women parading in their ‘birthday suits’. During the few minutes that I watched the film my sense of decency was deeply offended.’ (Mrs AJC, Truro)

- ‘What may we look forward to – the mind boggles – simulated orgies in Westminster Abbey perhaps!’ (Mrs NW, Tynemouth)

Mary Whitehouse wrote to the IBA on behalf of the National Viewers and Listeners’ Association to question the legality of the broadcast under the terms of the Television Act, which imposed a requirement not to show anything ‘which offends against good taste and public decency’. One viewer wrote repeatedly to complain not of the film itself but about a preview of the film which was screened without prior warning at 7.25, immediately after the religious programme Stars on Sunday.

These comments were nevertheless mild compared to the treatment received by The Killing of Sister George. The IBA and the ITV companies were prepared for controversy because the film had initially been refused a certificate by the BBFC when released in 1969. The GLC had issued a local ‘X’ certificate to allow it be released, uncut, in London and the BBFC had subsequently relented and granted an ‘X’ after requiring a three-minute cut to a lesbian seduction scene. The print received by ITV was the uncut version, but after internal discussion it was decided to cut the print to ‘take out some of the explicitness’ (some companies would not agree to show it unless this was done). The edited sex scene was not broadcast until after 11.00pm.

https://youtu.be/59ErX2HxGf8

As expected, there was a large volume of letters. Several complainants wrote to their MPs as well as to the IBA, and in what case an MP himself wrote in to complain.

- ‘The film The Killing of Sister George was sheer porn and to have this sort of thing put on during a Sunday evening I think is utterly irresponsible...my son and I were watching the television in all innocence then to find that I am faced with four letter words and lesbians...’ (Mrs GH, Peet Hall)

- ‘From a quick glance at the title I assumed it was a straightforward mystery story, and was appalled as the plot unfolded that the film chosen for this peak viewing time was based on such an unsavoury subject, and, furthermore, dealt with it in such explicit detail.’ (Mr THH Skeet, MP)

- ‘...if there is no censorship on TV films and parents are not in the house the younger Generation will become more corrupt than they are at present and we are all trying very hard to make England a better place to live in.’ (Mrs EB)

- ‘I am a Londoner and very broad minded we all know these things do go on, but I personally think they are very bad material for a play. Had my two married sons been present I would have definitely felt embarrassed...’ (Mrs IJG, Clwyd)

- ‘Whilst this type of film can be shown before a restricted audience of over 18 years in the Cinema, I consider it downright disgraceful that such pornography should be exhibited on a Sunday evening to any young child who cares to watch in his or her home.’ (Mr GBH, Prestbury)

This last letter was sent to Nicholas Winterton, MP, who agreed with the sentiments but regretted that Parliament was unable ‘to intervene directly’ in controlling the content of TV programmes. It was also reported in newspapers that a party of eleven girls from a Surrey boarding school who had been refused permission to watch the film staged a walk-out the following morning and were last seen hitchhiking along the A3. A police spokesman was quoted as saying: ‘I don’t think we have lost them or that they have been taken away – I think it is more a case of the girls going off for a walk.’

One of the stations that did not show the film on its first broadcast in September was Westward, but a group of at least ten letters sent by different correspondents to the chairman of the company, Peter Cadbury, all copied to the chairman of the IBA, Lady Plowden, and all making the same points were clearly the result of an orchestrated campaign (the film was shown there anyway in October). Examples:

- ‘As a Christian Retired School Teacher of 40 years service, in all age schools, I feek compelled to write and beg your for the sake of all CHILDREN who have not yet been contaminated by Porn, Crime, and the other indecencies of this age, that you will refrain from showing X and AA films on our screens.’ (Miss VLF, Cornwall)

- ‘My special plea is that The Killing of Sister George is not shown on Westward TV unless the lesbian love scene is cut out. The moral of the story would thereby be unaffected. I appeal to you for the sake of our young people – the future adult generations – and for the sanctity of the good and pure aspects of our national heritage.’ (Mr NP, Cornwall)

- ‘I cannot believe (at least, I try not to believe) that among TV programmers there is a deliberate, planned campaign to pollute society by infiltrating filth. But something like this seems to be the only explanation for what is happening.’ (Mr MB, Falmouth)

Shirley Temple

The second major controversy of the year arose from a different and quite unexpected quarter. On 3 March the Daily Mirror broke an ‘exclusive’ front-page news story that the films of 1930s child star Shirley Temple had been banned from children’s television by ITV programme planners. The newspaper quoted an unnamed IBA spokesman who said that Temple ‘had no relevance to modern children’ and would be ‘more likely to appeal to the nostalgia of grandmothers’. Films of similar vintage starring Will Hay and Old Mother Riley were nevertheless approved as acceptable children’s fare. An unnamed ITV executive was quoted as saying that the ban was ‘ludicrous’. Other celebrities had been approached for comment, including Les Dawson and Mrs Rolf Harris, whose 10-year-old daughter Bindi was a fan of Temple’s and who called the ban ‘laughable’. Other newspapers, including the Daily Mail, later the same day and on subsequent days, picked up the story and not unexpectedly ran with it. The Mail quoted another unnamed IBA official as saying: ‘There is no ban on Shirley Temple...we suggested to the ITV programme company that they should surely find something less wet than Shirley Temple to fill their children’s film hour’. A week after the story broke a letter appeared in the Mail from the IBA’s head of Information, John Guinery, again denying that there was a ban and saying that the IBA had simply suggested that one particular children’s weekday slot ‘can be better used’.

In the interim, a pile of letters had been received by the IBA from viewers protesting at the alleged ban – some from adults, variously outraged, sarcastic or distressed, and in several cases pointing out the irony of the decision when a lot of ‘pornographic’ and violent films were being allowed on the air. One American viewer wrote a complaint in verse, which was answered by a poem from an IBA officer. But many letters were from children upset that their favourite star had been taken off the air. Among the dozens of letters – some clearly organised by schoolteachers, other apparently written at the volition of children as young as six – were several enclosing petitions with lengthy lists of names of children protesting the ban and asking that it be overturned; some mentioned surveys of classmates that the children had conducted (‘27 out of 28 voted Shirley Temple’). Some children made quite sophisticated critical remarks about ITV and hoped that it would go bankrupt or that the executives responsible would lose their jobs. The letters came from both boys and girls; all were in Shirley’s favour and pointed out how out of touch ITV was with real children’s tastes and interests. ‘I think your ITV chiefs are a bit cracked,’ wrote a sixteen-year-old boy (SR) from St Alban’s. ‘We love Shirley Temple...If you don’t think again I’ll be converted to the BBC. Long live the BBC.’ Other examples:

- ‘I think you were very wicked to ban Shirley Temple’s films...In one of the papers it said ‘Christine Jenkins, 9 of West Ham’, never heard of Shirley Temple. Well her mum doesn’t tell her or she isn’t interested in her films or she can’t read. (I hate her).’ (Miss K, 13 years – a four-page letter)

- ‘My friends and I are very, very wild with you. First you take off [the TV series] Planet of the Apes and then you ban the Shirley Temple films. It’s all very well for the ITV programme chiefs to laugh but they wouldn’t be laughing if they got sacked...I am not in the upper class because I am only a secondary school girl, but I have my own opinions and so do others.’ (CH, London)

- ‘I do not think you can know many little girls or else you would not make yourselves look so silly...I would like you to think again, stop being daft and put them back on again.’ (Caroline, 8, Andover)

Further investigation by the IBA revealed that the ‘ban’ was not what it seemed. One ITV company (Thames) had sought approval for a season of films in children’s viewing time on Thursday afternoons that included several Shirley Temple films. Two IBA programme officers ‘not happy’ about the choice of Temple but the option of including her films in future seasons if the present proposed one was a success was left open. This had been relayed by Thames’ programme planner to Leslie Halliwell as film buyer and to the distributor of the films, Warner Bros (on behalf of 20th Century-Fox), to explain why a package of thirteen Temple films was not going to be bought as planned. A ‘leak’ had then occurred to the Mirror. It was suspected that the unnamed executives quoted were figments and the quotations had most likely been made up. The source of the leak was suspected as being either Warners or Halliwell, but this was never proven. Despite the IBA’s repeated protestations that there was no ban across the network but simply a ‘no’ to the particular company and season concerned, the affair ran and ran, proving a considerable PR embarrassment, but did not stop Temple’s films being screened by ITV altogether.

Tentative Conclusion

At the beginning and end of the decade, two independent reports commented on what they saw as the disappointing state of the scheduling of films on British TV. The reports – by Ed Buscombe in 1971 for UNESCO and in 1979 by Lynda Myles, former director of the Edinburgh Film Festival and relayed specifically to the BBC – found that the broadcasters did not take the scheduling of films seriously enough and did not thereby encourage a serious interest in cinema by the public. Both used the word ‘camp’ to describe the attitude towards cinema frequently reflected in on-screen presenters and the Radio Times’ films column. This complaint does not, on the whole, seem to me to be warranted: the selection of films and their ‘placing’ seems far more reasonable and adventurous, within the limits of appealing to a generalised mass audience, than is the case today, for instance, despite the far greater availability of films across a far larger number of channels. Imaginative scheduling strategies, some of them quite risky, did take place and on the whole the viewing public as well as the cinema itself seems to me to have been well served.

Dr Sheldon Hall