by Lee Christien

Watch the ViewFinder BoB Playlist for this essay

Henry Rollins, whilst reflecting on his career and time as lead vocalist in the American Hardcore band Black Flag, had the significant insight that “home, if I have one, is the road.” The way we might frame a group of celebrated movies filmed during the period of the initial Hardcore scene — The Decline of Western Civilisation Vol. 1 (1981), The Slog Movie (1982), Another State of Mind (1984), Black Flag: Live (1984), Reality 86’d (1991) — is open to revision now, due to a number of more recent movies which have returned the spectator to this most fascinating and durable of American music cultures; including Instrument (1999), Salad Days (2014), and Desolation Centre (2019).

Central to all of these cultural documents is the domestic and new approaches to the facilitation of home for a musical subgenre that faced police censorship. It is also the spectre of the home, along with its ancillary function and social structures, that signifies the loss of a certain vision of American family life, literally found in-between the tracks, in these films which document the nascent underground scene of the 1980s. The economic and corresponding cultural values of the ‘overground’, as Ian MacKaye — counter-cultural icon and boyhood friend of Rollins — might have it, became conspicuous by its actualised indifference, and indeed absence, manifested in cultural terms, for a generation subject to the austerity of ‘Reaganomics’.

What we see in these films is a counter cultural avant garde that rejected the notion of the 'ideal home', which, by the 1980s was already unobtainable for many working-class adults and children. Stuart Swezey’s Desolation Centre (2019) presents the consequences of this conjuncture found in the mise-en-scène of Penelope Spheeris and Dave Markey’s films which first documented the early Hardcore scene. The surrounding events of the action in these films is captured amongst the collapse of the civic, which led to the development of new cultural zones found in the intermissions between live performance. The intriguing argument of Swezey’s film is that these new subterranean DIY spaces transitioned into the megafauna of the contemporary festival industry exemplified by Burning Man, Lollapalooza, and Coachella. I argue that this transition is mirrored in the performative and artistic content of Rollins’s own career trajectory which can be located in the following series of films discussed in this essay.

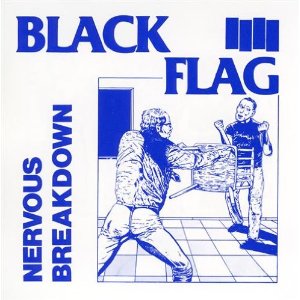

In a review of Spheeris’s The Decline of Western Civilisation Vol. 1 (1981) for Viewfinder Magazine, Dr Helen Reddington describes the way that the documentary “sandwiches live renditions of the songs of each band” with interviews conducted “sometimes backstage and sometimes at ‘home” as the LA punk scene’s participants are interrogated. It is in Spheeris’s framing of the domestic situation of Black Flag members Ron Reyes and Robo that the absence of the home comes to feature prominently in one of these interview segments. The discussion with this early iteration of Black Flag is conducted in the rehearsal room of a converted church which we find out actually doubles as a living space for Reyes and Robo. The sleeping quarters of these young musicians are depicted: a door opens into a small closet whose interior stone walls are decorated with graffiti, a colourful sheet covers a small rectangular hole in the celling where Robo sleeps. The dream of youth literally burrowing up towards the chancel, nave, and transept from underneath, buried by circumstance below in the living mausoleum of this subterranean youth culture. Despite Reye’s rhetoric, this is a desperate situation and at the margins of the film is a record of how music provided a context where those economically marginalised could exist exterior to the denigration, distress, and humiliation that accompanies structuralised poverty and inequality. Rollins, who prior to joining Black Flag was a dedicated early fan, describes the impact of the group’s first record cover, which,

'[…] said it all. A man with his back to the wall baring his fists. In front of him another man fending him off with a chair. I felt like the guy with his fists up every day of my life.' (2)

The deep impact of this pop cultural phenomenon is celebrated in Dave Markey’s The Slog Movie which explodes the premise of Spheeris’s films that punk can be read in terms of a linear historical development, a problem from which many of the more recent films also suffer. It was, rather, a new beginning and a rejection of the notion of tradition. Markey, here, recalls his feelings at the time about the importance of hardcore: 'Mainstream culture got more stupid, as the Republicans and the Christian Right started coming to power, you knew it was all wrong. The music helped make things seem better, it offered an alternative to the church, and the state, your parents […]'. (3)

Black Flag, Nervous Breakdown record cover

The Slog Movie is bookended by footage of two children on a deserted Los Angeles street graffitiing an abandoned home in obscure logos used to represent the musical groups: expressive character fonts, ambiguous pictograms, and irregular shapes are scrawled over the very surfaces of an untenanted domiciliary. They hang around in the detritus of the collapsing and contracting social system; reclaiming the space with the new visual language of this emergent underground culture. The Slog Movie is reminiscent of ‘Decline of Western Civilisation’ in so far as it uses the same structure. For example, the ‘sandwiching’ of the live musical performance of songs between talking heads and interviews is familiar and in keeping with this popular formula, but it innovatively deploys a radical distance in narrative terms through the editing and refreshing perspective of its content that like Markey’s unreleased Black Flag tour movie, Reality 86’d, verges on the psychedelic. Markey does not stage the live footage in the formalist manner that Spheris does, he instead captures the performances from the position of the fans i.e. below the eyeline of the performers. The camera angles embody the perspective of the spectators whose partial view moves upwards, tracking shots cut in sideways, and the frame jolts about in the crowd. In the shadows, they gaze upon the new anti-stars convulsing on that formerly unobtainable stage now drawn close, a technique deployed in both The Slog Movie and Reality 86’d.

Onto the stage, a skinny, shaved headed, and topless Rollins exuberantly bounds, pacing back and forth, snarling, blasted by the roar of the music, in the last live performance featured in The Slog Movie. 'Thirty five dollars and a six pack to my name', shouts Rollins to a partially obscured crowd. Here, we see Rollins, the exemplary fan of Black Fan, newly elevated to the position of frontman, as he performs the song ‘Six Pack’. The wiry frontman mimes to the audience the repetitious drinking of cans of beer, thereby, patronisingly illustrating the suspension of active life described in the song – a present endlessly deferred in favour of the approved consolations of consumerism for the working class. Newly relocated from Washington D.C., Rollins leaves behind the take-away restaurant, the deserted streets, unstable home and, here, appears on screen as the new reality before the movie segues into a voice-over about the potential threat posed by nuclear missiles. The potentiality of ballistic technologies, whose presence looms over the minds of the urban domestic population, is parodied as energy and vitality, and like Frankenstein’s creation (a melange of bodily detritus), the dancers who appear in these films are jolted by an electrifying stimulus beyond discursive comprehension.

This is an example of the most exciting scenes found in Markey’s films where the crowd blot out the frame of the stage from the edges, those performing obscured, cancelled out, re-configured. Here, new bodily relationships transverse and interpenetrate in the cacophonic fuge of the forceful sound and movement. It is perhaps unsurprising therefore that we find an intimate framing of the ‘live performance’ in close correspondence with other sections that draw in on the encroaching crowd. What is noticeable across these movies is that the response this new youth culture received from wider society impacted a sense of group identity and solidarity amongst its ardents. For example as Thurston Moore has observed of the Slog Movie its style discloses how “the scene dispersed by cops was a life lesson for those early 80s kids and one that defined a lot of outlooks to the future”. Moore’s other insight is that Markey, an active participant in the scene, “at once captures the substrata of L.A. 1st generation hardcore by hanging out with it in the backyards and empty matinee gigs it crashes around in.” (4) A common theme across all of the movies under discussion here is how the breaking down of the division between performers and audience led to a broader clash between repressive societal norms and the promise of a freeing subcultural identity.

In Another State of Mind (1982), directed by Adam Small, the narrative follows two LA group’s, Youth Brigade and Social Distortion, as they drive city-to-city across the USA in a repurposed yellow school bus. This movie details life on the road including: the highs and lows of the practicalities of putting on shows in other cities, the confusion of transit and psychology of proximity, and the network of houses run by and open to travelling groups of punks. One of the most moving scenes is a welcome dinner at the Calgary Manor, a punk run house, for this disparate group of personalities on the verge of interpersonal dissolution. This glimpse of the alternative network which arose to briefly support this new performative artform that reclaimed the home as a communal space finds joyful expression in the unbridled welcome extended to the travellers: sanctuary, food, dignity. These are material comforts and social values found lacking elsewhere in the film, which features interviews with street children such as Manon Brière and Marcel. The comradery and excitement of punk and the vista of opportunities it seems to promise on the road comes to a dramatic end in Washington, D.C. where the enterprise of the tour collapses as the school bus breaks down on a busy highway. The final act of the group as a unit is to collectively push it up off of the busy road in an iconic scene whose background is the imposing civic and political buildings of The Capital. The touring group find sanctuary at the Discord house, home to Discord records: a successful label run by Ian MacKaye, Jeff Nelson, and others whose story is revisited in Salad Days (2015) directed by Scott Crawford.

The story of Discord is inseparable from the story of the search for new ways of living and extending the space of the home where concepts of family and the domestic were redefined to include a concern for the wider community. The DC punks and Discord band Beefeater in their song ‘Reaganomix’ observe how as the queue for the soup kitchen gets longer the economic policies of the New Right bear similarity to the simplicity of a traditional home-made recipe that requires the addition of the following ingredients: ‘one old asshole and an entire county’. In this context, Salad Days follows the development of the hardcore scene into a countercultural force, literally Positive Force, which emancipated creativity at the same time as it rooted it to social relationships: anti-war and anti-poverty campaigns, benefits and education focused on addressing the Aids Crisis. The participants in Salad Days and Instrument — a poetically structured documentary collaboration between the group Fugazi and director Jem Cohen —depict the home and the domestic as something potentially transformative.

It is a different vision to that of the earlier hardcore films with the substrata populating the vignettes who speak to the home and the domestic as spaces, first, ravaged by the intrusion of poverty, and second, as a lost past which has now given way to Black Flag’s call to arms: ‘Spray Paint the Walls’. Their ‘backyards’ and the ‘empty Matinees’ are as porous as the new fluid roles and experiences on offer for the participants. The vignettes in-between the performances remind us that the crowd are as imperative to the creative act as any talented individual or idea: the trajectory of this somatic crowd, who mirror the ballistic basis of techno-scientific society in their musical phrasings, responsive bodily movements, and aesthetics are in the process of creating a new space which as Swezey’s movie argues came to mine the political unconscious.

Desolation Centre offers the opportunity, with hindsight and an impressive array of archival footage, imagery, and stills, to look back on this hidden history where we witness how the dialectical dance of the crowd — comprising of both violence (pogoing, pushing, thrashing, charging) and pastoral care (rescuing, propping up, holding, mirroring) — became the justification for a clampdown which inadvertently solidified a rejection of the accoutrements of home. Sean DeLear recalls the hysterical media coverage of the downtown music scene which Swezey intercuts with vintage footage. Po-faced news presenters whip up anxiety about the wild youth and their incomprehensible dancing, “do you know where your child is?” they ask. In contrast, DeLear and Linda Kite describe the excitement of this multicultural and inclusive music scene which was pushed forward by ideas. As the scene grew, it attracted the attention of the police and in particular the chief of the LAPD, the infamous Daryl Gates, who DeLear describes:

'he was creepy, he was definitely racist, he didn’t like women, and he didn’t like anybody of colour at all. He didn’t like young people, he didn’t like young people having fun. The police would show up on mass, you didn’t know why, what was going on?'

The police harassment of the music scene is well documented (Rollins’s tour diaries feature the famous image of LAPD riot police entering a Black Flag concert) and it is refreshing to see a positive film detailing the creative response of young people to such regressive authoritarianism. It is at this conjuncture, where an artistic movement met forces intent on disrupting them that Swezey’s smart film really switches gear and adds to our visual imagination of this interesting period in American cultural history.

Like Markey and Crawford, Swezey was also an active participant in the Hardcore scene which he has also come to document in film. Fed up with the police harassment, Swezey and his peers had the opposite idea to the Discord scene. Whereas Discord rooted themselves to the home, the Desolation Centre removed themselves from the situation entirely, and simply looked beyond the city limits daring to stage bespoke events out of the sight of the authorities. What is unique about this film is the way it delves into the collective memory of these countercultural happenings, digging into the concepts, process, staging, and lessons learnt from each occurrence of the Desolation Centre. The first event was set in the Mojave desert with the Minutemen playing, and there is great fun in the recollections and excitement of this first happening – from the yellow school buses of music fans leaving the city, to the visually stunning backdrop of the desert.

The second event set at the foot of a mountain featured Mark Pauline, the performance artist, whose deployment of ballistics and explosives squares the utopianism of the scene with a dystopian undercurrent manifest in the jaded futurism of Survival Research Laboratories. It is the presence of both light and dark which expand the mythos of this short-lived and potentially dangerous scene – there is a hair raising moment in the documentary where a sheet of metal spins over the heads of an unsuspecting crowd. Pauline like other of the attendees (Perry Farrel of Lollapalooza et al) went on to have great success with the now familiar concept of the event experience, the fantasy world of the mega-festival. For today’s pleasure seekers such events are a temporary escape from the home, job, routine, to which they will then return.

Henry Rollins Live with Black Flag, 1983

Black Flag Live 1984 seems a more apt end to the story of hardcore rather than the idea that it morphed into these mega-festivals or into the heartening and amazing DC scene. Rollins by 1984 had morphed from fan, to exemplary hardcore punk, and then into a muscled, long haired, imposition of a human: the tattoo of giant sun on his back rises up over the future. Part-machine, part-animal, Rollins delves into the interior and exorcises the constraints of masculinity to a crowd seemingly at home in the venue: they sit on the stage, press into one another in unison as the vicious sound performed by Greg Ginn, Kira Roessler, and Bill Stevenson fluctuates in tempo, melody, and intensity similar to the finest moments of jazz.

Displayed here is a masculinity putrefying at the same time that it is vitalised by Rollins’s degenerate performance and parody: a view from below, from the margins, as the protagonist peers up from amongst the detritus and accumulating dirt of the shattered American Dream found slumped against the material consequences of the birth of the ballistoscene – social planning predicated on the cultural and economic production of projectiles. The sequential denouement of which is a trajectorial verisimilitude that finds purchase in the aesthetic debates of the underground. In the narrative arc of these films, the domestic sphere haunts the protagonists. The abandoned home is found to be a site of horror which drives the protagonist into a process of physical metamorphosis of either the space itself, its abandonment and quest for a new home, or in the interior struggle that comes to terms with the inheritance and barriers for the working class performer. Only the rats thrive in the ballistoscene, and Rollins adopts their viewpoint.

(1) Henry Rollins, Unwelcomed Songs (Los Angeles, CA: 2.13.61 Publications, 2002), pp. 14.

(2) Henry Rollins, Get in the Van: On the Road with Black Flag (Los Angeles, CA: 2.13.61 Publications, 2nd Edition 2004), p. 9.

(3) Stevie Chick, Spray Paint the Walls, (London: Ominbus, 2009) p. 216

(4) Thurtson Moore, Linear Notes for The Slog Movie, <http://www.wegotpowerfilms.com > [Accessed 29 September 2020]]

About the Author

Lee Christien is a PhD Candidate in the English, Theatre and Creative Writing Department at Birkbeck, University of London. His thesis, Captives of Classification: Unlocking the Representations of Animals from the Daily Occurrences, Library, and Cages of London Zoo, investigates the quotidian texts accompanying the deployment of a classificatory system. Lee has an MA in Sequential Design from the University of Brighton. His Creative Writing research project titled: A Day in the Life of Ashley Barnes, Illustrated by the Dewey Decimal System was purchased by the University of Brighton’s Artist's Book collection.