Elena Dirstaru, doctoral researcher at the University of Essex, reports on her recent research placement with Learning on Screen, organised by the CHASE consortium.

I am a documentary filmmaker and doctoral researcher at the University of Essex, currently in the second year of my PhD, researching documentary interviews, and their link to space, voice, and authoritative discourses. I have previously directed two documentaries focusing on women’s rights, Monashay (2013) and But They Can't Break Stones (2015), both screened at international film festivals internationally, with the latter also being nominated for a Learning on Screen Award.

During the first half of 2016 I worked on a research project at Learning on Screen as part of a placement organised by the CHASE consortium of universities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I researched a collection donated to Learning on Screen over a decade ago, called They Made News. This collection of audio tapes and film reels contains interviews with newsreel cameramen who mainly worked during the Second World War. It was initially meant to be a television documentary focusing on newsreel cameramen, but after a preproduction and production process littered with mistakes and bad luck, the series never surfaced. The director admitted to mistakes such as not hiring a professional researcher, not having enough crew, and lamented the insufficient funds allocated to the production, which ultimately meant that the series never got made. The editing process stopped after a rough cut, and only very few people saw it.

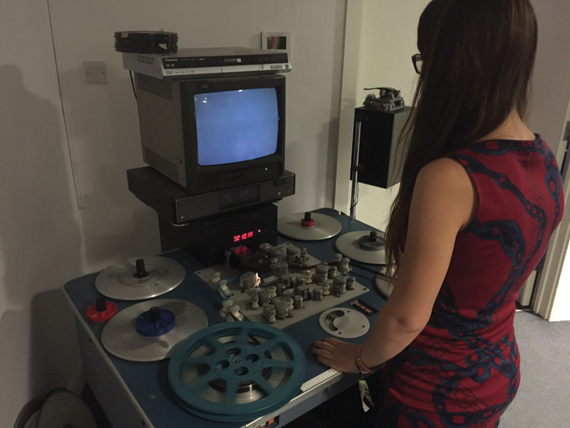

Elena digitising They Made News on our Steenbeck.

It was this rough cut, and some rushes, that were donated to Learning on Screen by director John Edwards. My work focused on researching and digitising these tapes, as well as listening to them (possibly for the first time since the production ceased) and transcribing some of the most important parts of the interviews. The research part was possibly the most challenging, as there is very little written on this collection. As such, my research focused more on the individual cameramen interviewed for the series, and learning more about their work, in order to better contextualise the collection. Newsreel cameramen like Ted Candy, Ken Hanshaw, and Cedric Baynes were interesting to learn about, as they dedicated their lives to their jobs and were involved in filming some of the most important events of the twentieth century.

Listening to their interviews was even more fascinating, as they candidly discuss their experiences as newsreel cameramen. They talk about the dangers involved in filming during the war, and the loneliness that came with the cameraman lifestyle, spending Christmases filming soldiers in Seoul, missing family events, and spending long periods without seeing their loved ones. I was surprised by how common this seemed to be, as all the cameramen interviewed touched on this issue, some emphasising it more than others. It seemed to be one of their greatest regrets, but at the same time one of the greatest sources of pride, that they always put their job first. Ken Hanshaw said that he never saw it as a job, because he could not have coped with it as such - he saw it as a way of life, and he always did everything he could to satisfy this way of life. Another emerging theme is the dangers that they subjected themselves to. During the war especially, the newsreel cameraman job was dangerous, and many of them pointed out that there were only few cameramen who survived unscathed. Many of them were physically injured, losing limbs; some lost their lives, and ever more were emotionally scarred by the horrific images they had to film. Despite all this, all describe their job as a passion; they were very happy to have been able to document important world events, however terrible.

Digitising and archiving the tapes presented a completely different set of challenges. I learnt how to digitise audio tapes and film reels, and used equipment that I would not have had access to anywhere else. I started with the audio tapes: learning how to digitise, listening to new interviews, and learning about the tapes all at the same time. As a filmmaker, I have only worked with digital cameras and digital sound recorders, so it was very insightful for me to work with magnetic audio tapes (and later film reels) to better understand how technology has changed, and how this evolution has affected filmmaking over the last two decades. It is extraordinary for a researcher to have access to this content, the technology used, and an insight into what making a documentary and editing a film was like just 30 years ago.

They Made News film canisters.

It is a shame that the study of newsreels isn’t more prominent on undergraduate film courses, because they are such a good learning tool. As part of my research I watched many films shot by the cameramen in the They Made News series, and it was a completely new field for me, even though I have a background in Film Studies and filmmaking. Studying newsreels was never part of the curriculum, and their importance never really occurred to me until I started working on this project. Not only are they fascinating from a filmmaking perspective, seeing technology evolve when you watch newsreels over a certain time period, but also from a historical perspective, to watch important historical events happening on screen. Again, this is something I never had access to when studying history in school. Newsreels are a valuable learning and teaching resource, and I started to use them in my teaching work at the University of Essex, when discussing technological advancements in filmmaking, film grammar, and the history of documentary filmmaking.

They Made News is a valuable collection, as it provides insight into newsreel cameramen’s lives and the thoughts they had about their careers after they retired. These interviews are unique, and some of the cameramen interviewed have only spoken publicly about their careers in the context of this series, making it very unique and interesting, as well as valuable from a historical perspective. The series provides insights not only into the newsreel industry of the first half of the twentieth century, but also into what can make a series successful, and the vital mistakes that can stop a production from reaching its audience, be they financial worries or bad decisions. Overall, this was a very interesting and enlightening research project, which should hopefully be useful to many others.

Elena Dirstaru