As part of the British Library’s commitment to delivering a multimedia research environment, they are exploring the potential of speech-to-text technologies for finding non-textual content. Luke McKernan, Lead Curator, News and Moving Image at the British Library, brings us up-to-date with their efforts.

About the author: Luke McKernan is Lead Curator, News and Moving Image at the British Library. He is the author of: Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897-1925 (University of Exeter Press, 2013); Shakespeare on Film, Television and Radio: The Researcher’s Guide (BUFVC, 2009), co-editor with Eve-Marie Oesterlen and Olwen Terris; Moving Image Knowledge and Access: The BUFVC Handbook (BUFVC, 2007), co-editor with Cathy Grant; Yesterday’s News: The British Cinema Newsreel Reader (BUFVC, 2002), editor; A Yank in Britain: The Lost Memoirs of Charles Urban, Film Pioneer (The Projection Box, 1999), editor; Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema: A Worldwide Survey (BFI, 1996), co-editor with Stephen Herbert; Walking Shadows: Shakespeare in the National Film and Television Archive (BFI, 1994), co-editor with Olwen Terris.

About the author: Luke McKernan is Lead Curator, News and Moving Image at the British Library. He is the author of: Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897-1925 (University of Exeter Press, 2013); Shakespeare on Film, Television and Radio: The Researcher’s Guide (BUFVC, 2009), co-editor with Eve-Marie Oesterlen and Olwen Terris; Moving Image Knowledge and Access: The BUFVC Handbook (BUFVC, 2007), co-editor with Cathy Grant; Yesterday’s News: The British Cinema Newsreel Reader (BUFVC, 2002), editor; A Yank in Britain: The Lost Memoirs of Charles Urban, Film Pioneer (The Projection Box, 1999), editor; Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema: A Worldwide Survey (BFI, 1996), co-editor with Stephen Herbert; Walking Shadows: Shakespeare in the National Film and Television Archive (BFI, 1994), co-editor with Olwen Terris.

The British Library has over one million speech-based recordings. These include radio broadcasts, oral history recordings, interviews, speeches and television news programmes. Making these discoverable by researchers traditionally has depended on catalogue records, sometimes supplemented by content summaries and searchable transcriptions. The first can be relatively quick to create but usually provide only rudimentary information about the content of the recording; the second are enormously time-consuming to produce, though of course hugely valuable.

… speech-to-text technologies have reached an exciting stage where they are close to becoming adopted widely for large-scale operations

This is becoming an increasing problem for research in a digital age. Full-text searching of electronic and digitised print has revolutionised what we can discover, but the digital research environment is not limited to the printed word. Television programmes, films, radio broadcasts, music recordings, images, maps, data sets and anything else that holds knowledge and can be expressed in digital form is ripe for discovery, and of course we do discover these on our various databases. But how level is the playing field? We search with words, and receive results largely determined by the word content of the digital object. An object that has fewer words attached to it has less chance of being found in an integrated, multimedia research environment.

At the British Library we are committed to delivering a multimedia research environment, where non-textual forms have an equal chance of being discovered as content in books, journals and newspapers. Fortunately much exciting and innovative work is going on that aims to uncover the rich intelligence embedded in digital objects through image searching, face recognition, video analysis and much more. Focussing on those one million speech recordings whose detailed content currently lies hidden from researchers, we have become particularly interested in the potential of speech-to-text technologies.

Speech-to-text technologies could transform how academic research is conducted. Such technologies take a digital audio speech file and convert it into word-searchable text, with varying degrees of accuracy, comparable to uncorrected OCR (optical character recognition) for text. What was pioneering science a few years ago has entered the mainstream, with speech recognition services becoming increasingly familiar to the general public as smart phone applications. However the technological challenge is far greater when it comes to tackling large-scale speech archives.

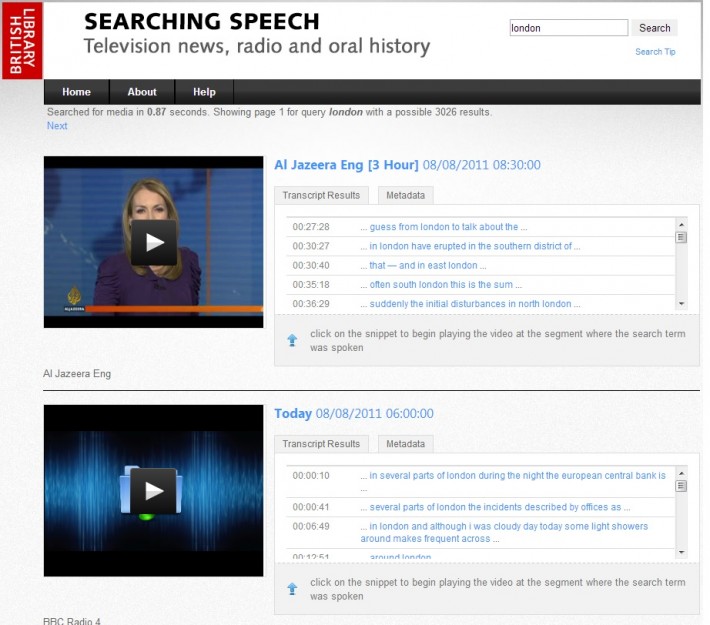

Over 2012-23 the British Library has hosted a research project, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council, entitled Opening up Speech Archives. Paul Wilson was co-investigator with myself, and Mari King was the project researcher. This has looked not so much at the technical solutions on offer but rather at what value such technologies might bring to researchers across a range of academic disciplines. The project involved interviewing researchers in groups and individually, getting them to test out trial applications and demonstrator services. We have surveyed the opinions of specialists in the field, asking where they think the technology is going, and we have built a test service, entitled Searching Speech, developed by GreenButton Inc. using the Microsoft MAVIS system (marketed under the name inCus). This offers 8,000 hours of audio and video, featuring television and radio news from 2011 (Al-Jazeera English, CNN, NHK World and BBC Radio 4), historic radio programmes and oral history interviews. Rights considerations prevent us from making this freely-available online, but the service can be consulted onsite by appointment. We also organised the Opening up Speech Archives conference in February 2013, which product developers, service providers, archivists, curators, librarians, technicians and researchers from various disciplines; and the Semantic Media @ The British Library workshop, organised with Queen Mary, University of London, in September 2013.

There are different kinds of speech-to-text systems, but essentially they work in one of two ways. Dictionary-based systems match the sounds they ‘hear’ to a corpus of words that they understand. If they do not recognise a particular word, as happens in particular with proper names, they will suggest the nearest word in their dictionary that matches it. This leads to all manner of comic results, such as one service which confidently reported that French troops had entered the city of Tim Buckley (meaning Timbuktu) or another service which read ‘Croydon’ as ‘poison’. There is nothing like the results one gets with uncorrected OCR for text, where gobbledegook is produced when a word is not fully understood. Dictionary-based speech-to-text systems (which form the majority) only understand complete words, and so frequently produce misleading answers. For example, one system we tried out picked up the phrase “no tax breaks for married couples” from a BBC TV news report. But the actual words used were “new tax breaks for married couples”. If the researcher uses the text results only and does not bother to listen to the actual recording, they will go away with the wrong answer.

There are different kinds of speech-to-text systems, but essentially they work in one of two ways. Dictionary-based systems match the sounds they ‘hear’ to a corpus of words that they understand. If they do not recognise a particular word, as happens in particular with proper names, they will suggest the nearest word in their dictionary that matches it. This leads to all manner of comic results, such as one service which confidently reported that French troops had entered the city of Tim Buckley (meaning Timbuktu) or another service which read ‘Croydon’ as ‘poison’. There is nothing like the results one gets with uncorrected OCR for text, where gobbledegook is produced when a word is not fully understood. Dictionary-based speech-to-text systems (which form the majority) only understand complete words, and so frequently produce misleading answers. For example, one system we tried out picked up the phrase “no tax breaks for married couples” from a BBC TV news report. But the actual words used were “new tax breaks for married couples”. If the researcher uses the text results only and does not bother to listen to the actual recording, they will go away with the wrong answer.

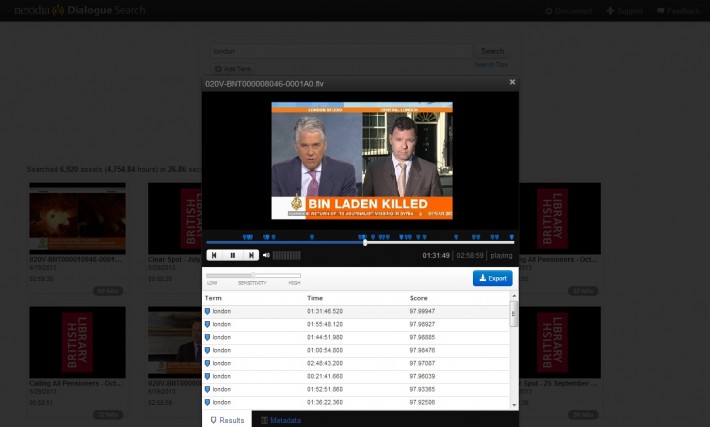

Other speech-to-text systems are phoneme-based. These recognise the building blocks of words rather than words themselves. For example, if one types in ‘Barack Obama’ into a phoneme-based service, it will search for ‘BUH-RUK-OH-BAH-MA’, bringing back results where that combination of phonemes can be discovered, or anything close to it. Such systems will always find something because they will bring up the best results they can find, no matter what the query. This leads to many ‘false positives’ – essentially, incorrect answers. We have had fun testing a demonstration service using recent American news programmes and searching for unlikely terms such as ‘turnips’. Inevitably the service found something (usually the words ‘turn it’ or ‘turn in’). Such systems do not present researchers with a transcript, or pseudo-transcript, because they do not store words, only units of sound. This is frustrating for the researcher who wants to browse search results, but the compensatory advantage is that a phoneme-based system can deal that much better with unusual accents or words. Most speech-to-text systems currently on the market have been trained on American English, and tend to be less effective with other accents.

There are a number of speech-to-text technologies and services using the technology which can be accessed online and which demonstrate the particular effectiveness of the technology when applied to particular collections.

- Democracy Live (http://www.bbc.co.uk/democracylive)

This BBC News site offers live and on demand video coverage of the UK's national political institutions and the European Parliament. Its search engine includes a speech-to-text system, built by Autonomy and Blinx. This enables word-searching across automatically generated transcripts (in English and Welsh), with results showing line of text highlighting the requested search term and a link to a particular point in time in the relevant video. It claims to have an accuracy rate of above 80%, and has been in operation for four years.

- Oxford University Podcasts (http://podcasts.ox.ac.uk)

This site offers podcasts of public lectures, teaching material, interviews with leading academics, information about applying to the University. The archive has been subject-indexed with automatic keywords generated using the popular open source speech-to-text CMU Sphinx. The service was developed by Oxford University Computing Services and its Phonetics Laboratory as the JISC-funded SPINDLE project.

- ScienceCinema (http://www.osti.gov/sciencecinema)

ScienceCinema features videos on research from the US Department of Energy and the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). It uses the MAVIS audio indexing and speech recognition technology from Microsoft Research, enabling users to search for specific words and phrases spoken within video files.

- Voxalead (http://voxaleadnews.labs.exalead.com)

Voxalead is a multimedia news test service, searching across freely-available web news sites from around the world, bringing together programme descriptions, subtitles and speech-to-text transcripts. It has been developed by Dassault Systèmes as an offshoot of its Exlead search engine. The speech-to-text element uses tools developed by Vocapia Research, which it combines with subtitle search and other metadata harvesting, with outputs such as map and chart view which demonstrate how powerful such technology can be in opening up and visualising audiovisual content.

- World Service Radio Archive prototype (http://worldservice.prototyping.bbc.co.uk)

This innovative demonstration service from BBC Research & Development and BBC World Service is an experiment in how to put large media archives online using a combination of algorithms and people. It includes over 50,000 English-language radio programmes from the World Service radio archive spanning the past 45 years, which have been categorised automatically using the CMU Sphinx open source tool to generate keywords. These are then reviewed and amended through crowdsourcing. The service is available to registered users only.

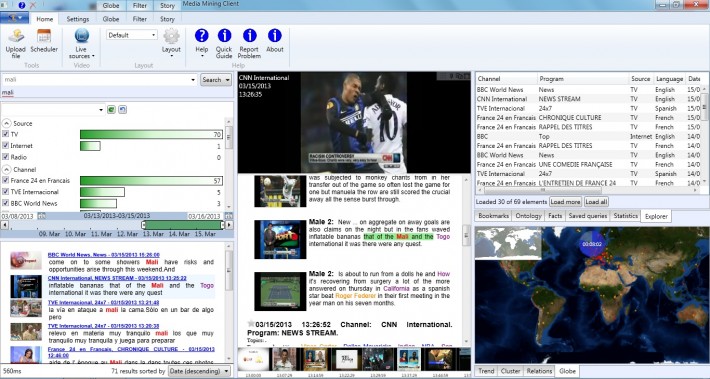

Speech-to-text technologies have reached an exciting stage where they are close to becoming adopted widely for large-scale operations. The recent Federation of International Television Archives (FIAT/IFTA) seminar on ‘Metadata as the Cornerstone of Digital Archive’, held in Hilversum, the Netherlands, in May 2013, showed how many broadcasters are now starting to think seriously of adopting speech-to-text systems to facilitate the subject-indexing of their audiovisual archives. Swiss-Italian broadcaster Radiotelevisione Svizzera has adopted speech-to-text to improve in-house indexing of their programmes, while Belgian broadcaster RTBF demonstrated the hugely impressive GEMS, a prototype for a semantic-based multimedia browser. This links data extracted from both traditional sources and speech-to-text, then combines it with Linked Open Data via a smart graphical user interface to connect the content to external services (such as Wikipedia pages). This demonstrates how speech-to-text applications are not simply about enhanced searching, but rather about extracting richer information from digital content.

Indeed the extraction of rich information is probably of far greater importance than the two areas where speech-to-text is usually supposed to be of greatest value: search and transcription. Speech-to-text provides an obvious additional element to search, opening up audiovisual content to word-searching alongside traditional text-based resource, but this alone is not enough, particularly where the results continue to be less than 100% accurate. The point is that speech-to-text is about so much more than simply finding a word or phrase in an audio file, useful though this primary function undoubtedly is.

The quest for transcriptions is misleading. Human-generated transcription services (where actual humans transcribe an audio file for you, at so much per hour) proliferate across the Web, and were a technology to be developed that could provide a perfect transcription automatically, then it would big business for somebody. But speech-to-text is not going to yield perfect transcriptions, certainly not any time to soon, if ever. The sheer variety of accents, modes of speech, the number of voices who may be speaking at the same time, all militate against such an ideal. A rough record can be generated, but accuracy rates can range anywhere between 30-80%, depending on the circumstances of the recording. A single voice in a familiar accent speaking directly into the microphone without extraneous noises will generate good results. This is why so many speech-to-text applications have focused on news programming, and it is how subtitles are generated for television programmes (a subtitle operator speaks the words they hear being said on a programme into a microphone, which then uses speech-to-text to create the rough transcript, the voice of the subtitler being easier for the system to understand than the direct broadcast). But unfamiliar accents or multiple voices recorded in more haphazard conditions only demonstrate the limitations of the technology.

The other problem with transcriptions is that they betray a fundamental suspicion of the value of the audio or video record in itself. We should not want to be creating transcripts as a substitute for listening to the original. That is a denial of the very value of the audiovisual record.

... the dream is to have anyone understand anyone else in whatever language they speak simply by speaking to them through their phone

Microsoft, Google and others are looking at speech recognition systems which can open up the vast audiovisual archive that the Internet represents, and have particular interest in allying the technology to translation tools for mobile applications. The dream is to have anyone understand anyone else in whatever language they speak simply by speaking to them through their phone. This Babel Fish vision will undoubtedly be transformative, but we have only to see the limitations of Google Translate in converting one written language to another to realise that these tools will only ever provide approximation rather than exactitude, at least for the foreseeable future.

Instead, the practical power of speech-to-text, particularly in an academic setting, must lie with its ability to generate keywords and facilitate entity extraction. We should not look at speech-to-text as generating a full reproduction of the words spoken, but rather as generating a rich set of data which can be linked to particular points in a file and linked out to other resources through open data models (though of course a full transcription will generate such rich data, and more). The BBC World Service prototype demonstrates the great value of extracting keywords in this way (though the keywords do not then link back to time-points in the digital file, which is a limitation), while the GEMS prototype shows how the Linked Open Data model can operate. We should use speech-to-text to uncover the intelligence embedded in digital objects. This will best enable the integration of audiovisual content with other, text-based resources, and will prove of greatest value to academic research in the years to come.

Luke McKernan

There is more information on the Opening up Speech Archives project at www.bl.uk/reshelp/bldept/soundarch/openingup/speecharchives.html.