Making your own films to a professional standard is getting quicker, easier and cheaper. Andrew Steele and Tom Fuller describe their experiences producing their series of short, sharp science videos.

About the authors:

Dr Andrew Steele is a physicist and science communicator based in London. He won FameLab UK 2012, and has explained physics on television, radio and online.

web: andrewsteele.co.uk / @statto on Twitter

About the authors:

Dr Andrew Steele is a physicist and science communicator based in London. He won FameLab UK 2012, and has explained physics on television, radio and online.

web: andrewsteele.co.uk / @statto on Twitter

Tom Fuller is an editor and graphic designer based in Oxford. Building upon a background in analytic philosophy, he is currently studying neuroscience. As well as working on Lab, Camera, Action!, Andrew and Tom recently launched the Scienceogram, a campaign raising awareness of how little we spend on scientific research: scienceogram.org / @scienceogram on Twitter

Tom Fuller is an editor and graphic designer based in Oxford. Building upon a background in analytic philosophy, he is currently studying neuroscience. As well as working on Lab, Camera, Action!, Andrew and Tom recently launched the Scienceogram, a campaign raising awareness of how little we spend on scientific research: scienceogram.org / @scienceogram on Twitter

Web video is an exciting new frontier in science communication: no longer do you need a massive budget and a mountaintop location to tell an exciting story about the world around us. Making a series of science videos is something we had wanted to do for a while, and we were fortunate enough to receive some grant money to buy a minimal set of kit, and have a go.

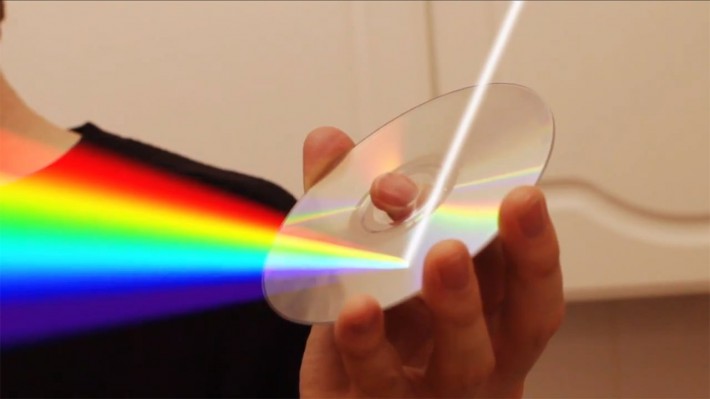

Lab, Camera, Action! is a series of short, presenter-led online videos, which aim to inform and engage on a range of topics in physics. Currently, there are episodes covering spectroscopy, superconductivity and the transit of Venus (with a combined 40,000 views between the Lab, Camera, Action! and Oxford University YouTube channels), and there are a few more in the production pipeline.

The project grew organically out of Andrew’s science communication activities and some rather silly videos made in collaboration with Tom in the past. It was only a matter of time before we thought about putting some of the things we’d learned to more serious use. And there clearly is an appetite for science videos online: YouTube is full of footage of amazing experiments, from super–slow-motion bullets in flight to flowers frozen with liquid nitrogen being smashed to shards, but many of them are either camera-phone footage from the lab, or (sometimes self-consciously) produced in a lo-fi, self-shot style. We wanted, within our means, to put together something more polished, which wouldn’t look too out of place in a conventional science documentary. Thankfully, ever-improving technology has made video production much more accessible in terms of both cost and complexity.

Financially, we were fortunate enough to win a grant which funded the project. Since Andrew was in the closing stages of his physics PhD, he was eligible for the EPSRC’s ‘Doctoral Prize Scheme’, which aims to encourage students to further develop projects started during their studies. One component of this grant was outreach, allowing us to buy some video equipment and software.

Natural lighting from a sunset over Oxford is combined with computer graphics showing the orbits of Venus and Earth.

Making even a handful of videos teaches you a lot about the production process, most importantly perhaps, that it’s much easier to re-film a section with minor errors than to try to cover mistakes in post-production. For example, in the photo that accompanies this article, you hopefully haven’t realised that we had to electronically remove an unfortunately positioned profanity carved into the bench! This would have been much simpler to fix during filming, by either getting Andrew to sit somewhere else or, if we were really desperate, using sandpaper … On a similar note, it’s always useful to have some extra people on hand to spot these kinds of mistakes – you obviously need at least a presenter and cameraperson, but allowing someone to pay full attention to the audio, or to directing the shots, makes the overall process a lot easier.

Filming a scene in the foyer of the Diamond Light Source, a particle accelerator in Oxfordshire. (photo: Joseph Caruana)

However, the key element, we’ve found, is the story. The first thing you need is an idea: a novel explanation of an interesting phenomenon, a cool demonstration, or something that viewers can make at home. In that respect, video is much the same as any other medium, and it’s important to prioritise the script before concentrating on the specifics of realising it. Since our videos are based around a presenter telling this story, they are basically mini-lectures, augmented with flourishes permitted by the format.

And there are numerous advantages to video, both practical and aesthetic. You can take people to places they couldn’t normally go, such as inside a particle accelerator; cuts can compress time so, for example, a large lump of superconductor can be cooled to −196ºC in moments rather than minutes; and presenters can interact with physically impossible visualisations of the phenomena they’re describing. We didn’t aim to be showy in using special effects; instead we used video tricks and explanatory graphics that add rather than distract.

Another reason it’s important not to get distracted by the technical trivia of filming is that, as photographers and videographers are wont to say, your camera doesn’t really matter—and, in this age of DSLR video, that’s truer than ever. Once you’ve got a video camera and microphone, most of what stands between you and the shot you’ve envisaged is ingenuity; extra money to throw at equipment mainly buys convenience.

We made Lab, Camera, Action! with a video-capable DSLR, a tripod and video head, a radio lapel mic and an external sound recorder bought with the grant money. (We did raid our camera bags to supplement the kit lens which came with the camera, though.)

However, what you haven’t got in booms and video lights you can make up for with MacGyver-esque improvisation. We’ve used everything from bike lights to an overhead projector heavily modified with aluminium foil to illuminate our shots; grabbed a high shot with a camera mount involving rubber tubing and cable ties; and discovered that, even allowing yourself dozens of takes, a weighted tripod is a mediocre substitute for a steadycam. In fact, here’s a challenge: can you work out which of our shots was completed with the help of a camera braced against the wheel of an upended bike?

We edited and produced the videos in Adobe Premiere, and used After Effects to add the graphics. Like all software, there is a significant learning curve—and After Effects has some serious limitations when it comes to 3D—but with persistence (and more than a little bit of patience), it’s usually possible to find a way to create what you’ve visualised on-screen. We found the internet to be a vital resource, with tutorials available for most popular software packages explaining how to produce just about any effect you can think of.

Since we wanted to reach a broad audience, YouTube was the obvious choice for distributing the videos, as it provides free hosting and is ubiquitous—this has helped us catch casual browsers, and get our work shared on social media. We’ve also found that the ability for people to simply embed the video player in other websites has been important: in fact, such embedding has been responsible for nearly a third of our traffic.

... online science communication is a double-edged sword

Online science communication is a double-edged sword: you gain access to a vast potential audience and concrete statistics, but with little idea of who that audience is, or whether a view of your video translates into genuine engagement, understanding or inspiration. You also lose the ability to personalise your explanation based on audience reaction, as you might in a live show or a one-on-one demonstration. However, the sheer weight of numbers might well make up for the unknowns; even our relatively modest 40,000 views would take years of live lecturing to surpass and, when videos go viral, views can stretch to the millions.

Though producing videos can be hard work, we’ve really enjoyed the process. It’s a creative way of sharing our enthusiasm for science, whilst geeking out and learning new skills: technical, narrative and cinematic.

We’d definitely encourage other scientists and science communicators to have a go at putting polished videos online. So, if you’ve got a cool demo, put the cameraphone away; beg, borrow or steal a reasonable camera, think about how best to tell the story, and have a go. The results are really worth the effort.

Dr Andrew Steele and Tom Fuller www2.physics.ox.ac.uk/lab-camera-action