The Kinonedelja - Online Edition in the Austrian Film Museum brings together the earliest work of Russian film director and theoretician Dziga Vertov. We provide a guide to the Museum’s Vertov collection, including his contribution to the Kinonedelja (Kino-Week) newsreels, now published online.

About the author: Adelheid Heftberger is curator of the Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna. She holds MA degrees in Slavic studies and comparative literature.

About the author: Adelheid Heftberger is curator of the Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna. She holds MA degrees in Slavic studies and comparative literature.

We leave the film studio for life, for that whirlpool of colliding visible phenomena, where everything is real, where people, tramways, motorcycles, and trains meet and part, where each bus follows its route, where cars scurry about their business, where smiles, tears, deaths, and taxes do not obey the director's megaphone - Dziga Vertov (20 March 1927)

One couldn't sum up his approach to film more fervently than the Russian director Dziga Vertov himself. The creator of well-known films like Man With A Movie Camera (1929), Enthusiasm (1930) or Three Songs of Lenin (1934), had also been a prolific writer and theorist when it came to propagating his Kinoglaz theory. Vertov can be seen as a predecessor to TV or online journalism – to shoot, process and project the images as fast as possible:

Twelve Minutes-Project of mobile film projection unit. Only twelve minutes transpire from the arrival time at the show location to the beginning of the screening - Dziga Vertov (Artistic Calling Card)

Another idea that Vertov nourished continuously was that of establishing a footage library, which could be used by everyone who was willing to work in accordance with his Kinoglaz theory. Material would arrive from all over, coming from a 'humanity of kinoks'. One of Vertov’s earliest ideas was to create an army of 'film scouts' in order to abandon the notion of a single author and proceed to mass authorship, 'not a coincidental but rather a necessary and all-encompassing global review of the world every few hours.' Mobility, interactivity and accessibility are the key-terms to describe this way of working, and would also describe the Internet fairly well. Vertov spoke of a 'negative of time', the 'possibility of seeing without boundaries and without distances' and even of a 'remote control of the camera.'

Vertov published many articles. Among the most famous ones are his early manifestos, speeches delivered to his fellow filmmakers and Soviet officials, composed treatments, scenarios and charts to visualize his complex montages. Most of these documents are held in the renowned Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI) in Moscow, donated by his widow and co-worker Elizaveta Svilova after Vertov’s death in 1954. But she kept some of the most interesting documents for herself, later bequeathing them the Austrian Film Museum.

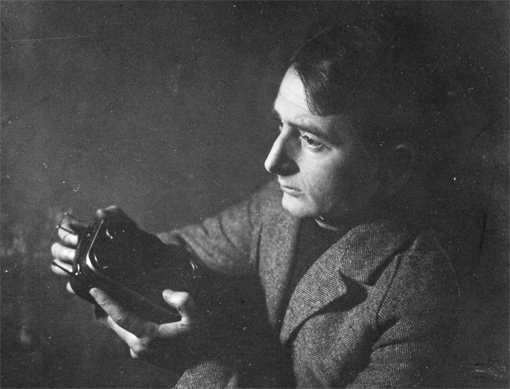

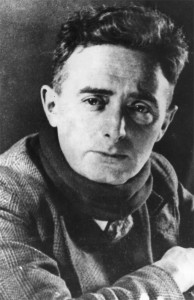

Dziga Vertov (Austrian Film Museum)

In order to understand better how parts of these precious documents found their way out of Russia, we need to look at some developments in the cinema context in Vienna in mid-1960. In 1964 two young film enthusiasts, Peter Konlechner and Peter Kubelka, founded the Austrian Film Museum, because they saw the need to establish a different film culture to the one already in place. Already from the start they included Russian films, especially the Russian Avant-garde, in their screenings. But Vertov had been on their agenda even before setting up the Film Museum and its own cinema – Peter Konlechner presented Vertov's Man With A Movie Camera on 23 April 1963 in the films club he headed at the Technical University. As early as 1967, the Austrian Film Museum started to collect films, writings, photographs, posters and other documentation relating to (and created by) the Soviet filmmaker and the same year the Film Museum published the first German translation of his selected writings. Five years later, in 1972 Peter Kubelka and Edith Schlemmer restored Vertov’s early sound film classic Enthusiasm, and in 1974 Peter Konlechner and Peter Kubelka presented a large-scale Vertov exhibition at the Albertina. In organizing these projects, the Film Museum established a close relationship with Vertov's widow and artistic collaborator, Elizaveta Svilova. Between 1970 and 1974 Svilova donated part of Dziga Vertov’s personal collection and papers to the institution, thus laying the foundation of what is now the Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum.

Today, this resource contains approximately 100 film elements, 170 original manuscripts and autographs (Vertov’s writings, sketches and editing schemes), 200 photographs (personal photos and work-related stills), 600 press clippings from around the world (primarily from the former Soviet Union and Germany), thirty-three original posters, and many other documents. Since 2004, the Film Museum has been renewing its 'Vertov tradition' of the 1960s and 70s. The collection is constantly being processed and (re-)evaluated by Slavicists and the museum’s research staff. It has been transferred into an online database, online since spring 2009. This online presentation of the Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum opens a window to the specific objects in the collection, but we also consider it as an invitation, a starting point, a virtual 'hub' for further research on Dziga Vertov, the artist and film theorist. It is our hope that the database will also be used to collect information about further Vertov-related materials, which are stored in other archives and museums. The database can provide a platform for potentially 'dormant' documents from all over the world and bring them to the attention of the scientific community as well as the broader public. These additional materials will not come to Vienna - but the Vienna database can identify their content, their characteristics and their physical location; or, in individual cases, offer a digital scan of the document in question. We aim to create a growing resource, which reflects the ongoing study of Vertov’s legacy and the new directions it takes. In 2006, the largest-ever retrospective of Vertov’s films to date was staged at the Film Museum, accompanied by a bilingual book which for the first time lays out the rich materials saved by Elizaveta Svilova: The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum.

Dziga Vertov (Austrian Film Museum)

Apart from screening Vertov's work regularly in our own cinema and at film festivals all over the world, efforts have been made to make rare documents available through DVD publications and recently online editions. In 2005, the Film Museum published a 2-disc DVD set on Enthusiasm and its restoration by Filmmuseum-founder Peter Kubelka. In 2010 another set followed containing two more Vertov films, Šestaja čast' mira (Sixth Part of the World, 1926) and Odinnadcatyj (The Eleventh Year, 1928). In addition to the films, the set also contains contextual materials about The Eleventh Year both in a supplementary ROM section and in the short-form video essay Vertov In Blum. An Investigation (2009), which serves to shed light on the complex use and re-use history of the footage in the 1920's.

The Kinonedelja (Kino-Week) newsreels constitute the first films of Dziga Vertov. In keeping with its tradition of publishing important works by Dziga Vertov digitally, the Film Museum made its Kinonedelja holdings available online in May 2012. The publication of the Kinonedelja – Online Edition marked the first presentation of moving images on the Film Museum’s website. The newsreels provide an invaluable record of life in the young Soviet Russia, then in the throes of civil war. A total of forty-three issues were produced between May 1918 and June 1919. Vertov joined the newsreel’s ranks as a secretary but by the fall of 1918 had taken on full responsibility for the series, defining the content and structure of each issue. In some cases, Vertov even served in the function of newsreel director. An average issue would usually measure 180 metres and contained five to six, occasionally seven different items, such as short actualities from the frontlines of the civil war or information about rallies or film portraits of activists and officials. The best cameramen of the time worked on the newsreels, including Aleksandr Lemberg, Aleksandr Levickij and Eduard Tissé. The footage they shot was later re-used by Vertov for his feature-length films, in accordance with this Kinoglaz-concept. The items are tied closely to the historical events of the time. At the centre of the 1918 issues lie a straight forward representation of everyday life during the Civil War and the political manifestations: Already in Kinonedelja No. 1 Lenin and Leon Trotsky appear before the camera. Pavel Dybenko, a hero of the revolution who would have to stand before the Revolutionary Tribunal due to a lost battle against Germany, also makes an appearance. In the Kinonedelja issues that appeared between January and February 1919, Vertov often includes documents depicting day-to-day life in the Red Army, for example how massive snowfall limits their daily work and army operations. Funerals of local officials frequently form a part of the Kinonedeljas, as do the effects resulting from recent international events, such as the murder of the German Spartacists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Dziga Vertov (Austrian Film Museum)

The existence of the Kinonedelja newsreels today is quite precarious. According to film historian Aleksandr Derjabin, Vertov later 'violated' some of his Kinoneldejas himself whilst in the process of making his film Godovščina revoljucii (Anniversary of the Revolution) in November 1918. Afterwards, Vertov was forced by Vladimir Gardin (then in-charge of the newsreel) to restore the footage – an action, in which he was only partly successful. Some items were lost forever and had to be replaced by alternative footage. The Austrian Film Museum holds prints of fourteen clearly identifiable issues of the Kinonedelja series. The prints originated from the Swedish Film Institute, where they had been rediscovered (in a collection on deposit by the Swedish Television) by scholar Anna-Lena Wibom in 1967. The 35mm black and white prints were digitised within the framework of EFG1914, a collaborative project among twenty European film archives aiming to digitise and publish around 650 hours of film footage related to the First World War by February 2014.

In addition to the films, accompanying paper documents relating to the Kinonedeljas are held in the Vertov Collection and are available online. These include fifty-two photos of title lists, each of which is available in two versions: a censored and uncensored version. In certain issues, images of Trotsky, Lev Kamenev (the former Russian ambassador in Vienna) or Grigorij Zinoviev were later removed after they had fallen out with Stalin.

Filmmakers have to be aware of new developments in their field. This is very much the case with Vertov. He frequently spoke of experimenting with new cameras, new lenses and embraced the arrival of sound film wholeheartedly. He dreamed of a documentary ‘radio-newspaper’, of tele-films and radio-films and voted for the 'organization of a visual and radio broadcasting station, a visual-acoustic central station.' (from ‘Replies to Questions’, 1930) The Austrian Film Museum would like to contribute to making his fascinating work available, not only for scholars but also for everyone interested in Russian film and Russian history – in Vertov they form an inseparable unit.

Adelheid Heftberger

Web Links Austrian Film Museum http://filmmuseum.at/en

Kinonedelja Online-Edition http://bit.ly/YlJ8n8

Vertov-Collection Online http://bit.ly/137qzHX

EFG 1914 – European Film Gateway http://project.efg1914.eu/