by Sheldon Hall, Sheffield Hallam University

In this article, I will be mainly concerned not with Channel 4 as a producer or distributor of theatrical movies, but as an exhibitor of films on television. While charged with the need to be innovative, experimental and to provide a real alternative to the existing TV channels, the channel was also obligated to cater to hitherto neglected sectors of the audience, including more mature viewers and those with minority interests. In the case of films this meant not only art-house and avant-garde works but also old movies – movies older than those typically shown by the BBC and ITV. This obligation it discharged with vigour, imagination and intelligence, resurrecting literally thousands of films from the ‘golden age’ of popular cinema, many of them never before shown on British television or not seen for decades.

This paper derives from a much larger project on the history of feature films on British television. In the course of research, and drawing also on my own personal experience, I have formed some general conclusions. One of them is this: if there can be said to have been a ‘golden age’ of films on television, then it was the 1980s and 1990s. To be fair, this was not only due to Channel 4: BBC2 in particular outdid its own past efforts in this period, though I would be inclined to attribute this at least in part to the stimulus of competition. Undoubtedly, however, Channel 4 acquired and transmitted a huge number of films that were unprecedented in their range and variety and that have not been matched by any broadcaster since (not even the great Talking Pictures TV).

Films were from the outset planned as a substantial element of the channel’s regular output. At a press conference in December 1981, Jeremy Isaacs promised fifteen hours of films per week – more than for any other type of programme – of which about six or seven would be in peak time. The job of buying films was entrusted to two individuals. Derek Hill (1930-2020) was a distinguished writer and cinema programmer of long experience, who had particular responsibility for acquiring independent and foreign-language films. Among them were the first seasons on British television of films from India, Latin America, Africa and the Arab countries. Hill was given virtually an open cheque book; in a note on ‘Future acquisition policy’, in a report submitted to Jeremy Isaacs (8 January 1982), he wrote: ‘There seem to be two schools of thought: those who believe I’ve acquired enough for our first ten years; and those who think I’ll have to be given Channel Five.’(1)

The task of dealing with the American and British majors belonged to Leslie Halliwell (1929-89). Perhaps best known now as the founder and original author of the reference books Halliwell’s Filmgoer’s Companion and Halliwell’s Film Guide, Halliwell was attached to Granada Television, the ITV contractor for North West England, as film scheduler and adviser. From mid-1968, he also served as chief buyer and negotiator for the whole ITV network. In this capacity he regularly purchased feature films in large ‘packages’ that could comprise a hundred films at a time, including both recent and ‘library’ (older) titles. Halliwell’s personal preference was for films made before 1953, and especially those of the 1930s. This decade, aside from the silent era, was the most under-represented on television, as it remains today.

Halliwell made occasional experiments in programming for Granada, such as recreating a typical ‘golden age’ evening at the cinema by supporting a feature with a short film, a cartoon and a newsreel. In 1982 Halliwell himself presented a season called Home Front, in which a feature film of the war years was accompanied by one or two shorts made under the auspices of the Ministry of Information. But the advent of Channel 4 provided far more in the way of opportunities, allowing Halliwell to programme films for a national rather than just a local audience, to mount more ambitious seasons, and to find a use for some of the older and more offbeat films controlled by ITV along with others that he was to acquire specifically for the new channel.

Many of the older titles Halliwell had bought for ITV and which were programmed only sporadically by local stations were transferred over to Channel 4’s control while Halliwell acquired more directly for it. In December 1981 he told the Yorkshire Post: ‘I have bought 1,000 films for them already and I haven’t even started.’(2) Five years later, in an article he wrote for the journal Airwaves entitled ‘Rediscovering the Golden Age for Channel 4’, he talked about having amassed ‘more than 2,000 of them at an average royalty of £10,000 each’.(3)

Halliwell claimed that he only ever received one complaint about the vintage films he had chosen, and that from a 67-year-old woman in Godalming. However the IBA Archives at Bournemouth University contain several letters about the number of black-and-white films being shown on television, from viewers who objected to them when they had paid for a colour licence. These were clearly in a very small minority. Halliwell reported an overwhelming show of support from viewers, manifested not just in correspondence but in viewing figures. His biographer Michael Binder quotes him as saying: ‘When you can show Conrad Veidt in The Passing of the Third Floor Back to an audience of five million you really feel that you have achieved something.’(4) The Passing of the Third Floor Back (1935) was a British film that had long been thought lost. Halliwell stated in his occasional column written for the TVTimes, ‘Film Clips’, that he had been able to trace a copy held by a collector only some time later to receive a brand-new print from the Rank Organisation, which had hitherto denied having any material on the film. It was the channel’s preferred policy to strike a new 35mm print of each film it acquired from the best available negative; if that was not possible then the best existing prints were located, sometimes via the National Film Archive (as it then was), and transferred to tape. In many cases, according to Halliwell, films whose rights were available or had actually been acquired could not be shown because no usable print could be found; he claimed that one in four prints had to be rejected as below acceptable quality. Nevertheless, over 1,000 new prints were made specifically for Channel 4’s use; these still exist and occasionally turn up at BFI Southbank or in film festivals.

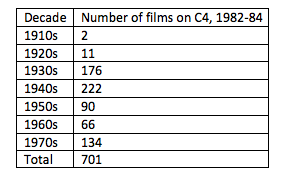

Of the 701 (by my count) pre-1980 feature films shown by Channel 4 in its first twenty-six months of broadcasting, no fewer than 411 were made before 1950, 189 of them before 1940 (see Table 1). This does not include the many short films used as afternoon ‘fillers’. Among the features shown for the first time on British television in this period were two on the channel’s opening weekend, Hell’s Angels (1930) and Scarface (1932), both produced by Howard Hughes; James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933), plus a season of the latter’s sequels; Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932); Samuel Goldwyn’s Bulldog Drummond (1929), Whoopee (1930) and Arrowsmith (1931), part of a season of the producer’s work; and Tod Browning’s once-banned Freaks (1932), which inaugurated a season hosted by Halliwell himself called What the Censor Saw, comprising key films in the history of film censorship. They had been kept off television partly by virtue of their age and partly due to contractual and copyright problems that had also kept some of them off cinema screens for years.

Repeats of films previously shown by the BBC or ITV comprised the bulk of Channel 4’s classics, but among them were many that had not been televised for a decade or more. To take one example: the first Hollywood ‘A’ picture by a major producer to be shown in its entirety on British television was a David O. Selznick production, The Young in Heart (1938). It was shown by the BBC on Christmas Eve 1947 and three more times over the next three years but after 1950 it was not revived again. Halliwell remembered it fondly and acquired it for Channel 4, scheduling it in a peak slot on the evening of Sunday, 9 September 1984, almost three-and-a-half decades after its last UK TV screening. In his book Halliwell’s Harvest, he records that ‘at the end, the off-screen announcer said “What a nice film,” and said it with every indication of genuine enthusiasm, while over the next few days a dozen or more people told me how much they enjoyed it and what a find it was.’(5) Halliwell himself was, however, disappointed by the film’s failure to live up to his memory of it!

These are all American films, and British classics were at first scarce on Channel 4. Many from the 1930s and 1940s were either tied up with rights problems or prints were hard to find. But gradually British films were acquired in vast numbers, including many that had never been televised before or not since the early days of television. Among them was The Seventh Veil (1945), which had been networked by ITV in January 1958 and then shown locally in various ITV regions before being withdrawn in 1960. It was then bought up by the Film Industry Defence Organisation (FIDO) in 1962 as a way of keeping it off the air. The Seventh Veil was not seen on British television again until Channel 4 revived it, twice, in 1984 (the second time to mark the death of its star, James Mason).

Abel Gance’s five-hour Napoleon (1927) was first broadcast (in two parts) in November 1983, one of eleven silent features shown in those first two-and-a-bit years. Seven of these, including Napoleon, were part of the Thames Silents project that sprang from Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s documentary series Hollywood, which had originally been broadcast on ITV in 1980 but was repeated on Channel 4. Though Thames Television (the London weekday franchise-holder, headed by Jeremy Isaacs) had financed the premiere presentation of the restored and reconstructed Napoleon, with a live orchestra, at the London Film Festival, later theatrical presentations of silent classics by Brownlow and Gill were co-sponsored by Channel 4, which subsequently transmitted them with recordings of the scores specially composed by (usually) Carl Davis. Two of the films broadcast in 1984, The Wind and Broken Blossoms, were preceded by video introductions by their star, Lillian Gish. Most of the other silent films Channel 4 showed in these years starred Buster Keaton, including both features and shorts, many of which had not previously been televised in their entirety, along with Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris (1928) and Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), one of the earliest features ever shown on television.

One of Halliwell’s most remarkable scheduling achievements built on his earlier work at Granada. After mounting two Channel 4 seasons about the Second World War, including one entitled The Gathering Storm that focused on films with pre-war settings, he embarked on a magnum opus: twelve weekly programmes, commencing in the autumn of 1984 and continuing after Christmas, under the title The British at War. The series brought together no fewer than forty-nine British films of the war years, including both fiction and documentaries, features and (mainly) shorts, some of the latter only a couple of minutes long. He introduced and linked them himself, the first programme going out on the afternoon of Thursday, 25 October 1984 in two two-hour sessions, either side of Countdown. The features in the season had been televised before, though some not since the early 1960s, but many of the shorts were not only new to television but had probably not been seen publicly since the war itself. The series was such a success that it was followed by two further seasons, America at War (which included the first television showing of Frank Capra’s documentary series Why We Fight) and Yesterday’s Britain.

I watched these series myself at the time and recorded many of the films. I was part of that generation of viewers who, had it not been for Channel 4, might not have seen hundreds of films that had never been available on home video; many of them are once again unavailable now. In acquiring and programming these films, the channel performed what for me remains its most valuable function in furthering film culture in the UK: that of an enlightened and imaginative curator, guiding the receptive viewer to unknown corners of film history and bringing out rare artefacts that, once seen, are never forgotten.(6)

Table 1

About the Author

Sheldon Hall is Reader in Film and Television at Sheffield Hallam University, UK. He is currently completing the first volume of Armchair Cinema: A History of Feature Films on British Television for publication by Edinburgh University Press in 2023.

Notes

(1) Document loaned to the author by Derek Hill.

(2) ‘Halliwell’s screen test’, Yorkshire Post, 19 December 1981.

(3) Leslie Halliwell, ‘Rediscovering the Golden Age for Channel 4’, Airwaves, 1986; online at http://www.lesliehalliwell.com/tv_film/index.html

(4) Michael Binder, Halliwell’s Horizon: Leslie Halliwell and His Film Guides (Lulu Publishing, 2011), pp. 215-6.

(5) Leslie Halliwell, Halliwell’s Harvest (London: Grafton Books, 1986), pp. 296-7.

(6) This article is a shortened version of a paper delivered at the conference Channel 4 and British Film Culture at BFI Southbank, November 1982.