by Sue Vice, University of Sheffield and Dominic Williams, Northumbria University

Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah (1985) is best known for three things: its enormous length, its harrowing interviews with Holocaust survivors and its lingering shots of empty sites where mass murder took place. All these elements are the product of careful and intensive editing. Hundreds of hours of interviews and location footage were worked into a film over nine hours long, in a complex interweaving of voices, faces and places.

The many reels of outtakes left behind are now freely available to view on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Scholars and historians have found in this footage many powerful testimonies not included in the film. But in this paper, we show that the unused location sequences also demand – and repay – scrutiny. We analyse sequences of this kind centring on a topic that is almost entirely absent from the final film: the difficulties and failures of international efforts at rescuing the Jews of occupied Europe. We do so by envisaging what kinds of imagery and, in some instances, dialogue could be cut and edited together for a short film-essay on this topic.

Our examples are the location footage of Geneva, filmed to be intercut with an interview between Lanzmann and the Red Cross director Jean Pictet, and silent reels of Evian which show the site of the eponymous and inconclusive 1938 conference on refugees. In both cases, the camera’s seeking out the features of national panoramas implies an expansion of Lanzmann’s concerns to include Swiss and French wartime events. Yet, the buildings of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC, or CICR in French) in Geneva and the Hôtel Royal in Evian are shown rather to be international sites. They are what Marc Augé calls ‘non-places’, by means of their impermanent occupants and supra-national implications. The neoclassical ICRC offices and Evian’s palace hotel are presented visually as ‘luxurious’ examples of the ‘transit points and temporary abodes’ that Augé claims constitute non-places such as these (1995: 78). The decisions taken in these locations condemned to ‘inhuman conditions’ those imprisoned in the refugee, concentration or extermination camps that are such abodes’ deathly converse (1995: 78). Therefore, despite the apparently stark contrast with the footage of urban and rural sites of former atrocity in Poland as these appear in Shoah, the sequences showing Geneva and Evian also lay bare the conditions that enabled genocide, among neutral nations and international organisations as well as in Nazi-occupied countries.

The Red Cross, Geneva

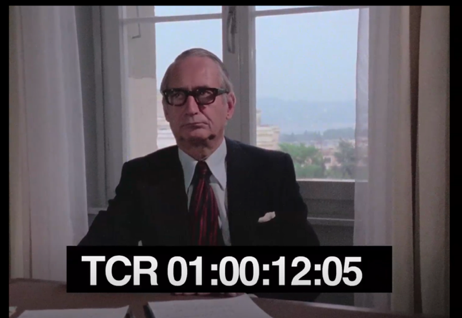

The footage of Geneva was filmed to accompany the outtake interview with Jean Pictet, over whose shoulder the cityscape is visible, and who was a prominent member of the ICRC and worked closely with its president Max Huber during the war.

By contrast to the urban imagery of old courtyards and communist-era housing blocks that represents Polish history in Lanzmann’s portrayal of Warsaw in Shoah, Geneva is shown as a city of leisure and prosperity. Our prospective film might therefore open with the director’s question to Pictet, ‘What does Treblinka mean from Geneva in 1942?’. This challenge to the imagination in the past and also the present would be heard over such imagery as that of a paddle-steamer on the city’s Lac Léman called Helvétie. The camera’s close-up on this archaic name for Switzerland highlights national continuity and pride, in a bitterly ironic contrast to the statelessness and murder invoked by the name of the death-camp Treblinka. This would be succeeded by extracts showing the smooth waters of the lake, and some of the many shots of swans, gliding along its surface or preening themselves at the water’s edge, which convey serenity and even obliviousness.

The names of the historic hotels lining the lake – Président, Ambassador, Hôtel de la Paix – suggest political acumen and diplomacy, an impression enhanced by shots of the Swiss national flag fluttering on the buildings’ roofs. During the war the ICRC itself inhabited the equally grand nineteenth-century lakeside Hôtel Métropole, connecting it even more closely to the ‘non-place’ of Evian’s Hôtel Royal. The Swiss flag’s eye-catching white cross on a square red background is a reminder of its inverse, which appears in subsequent sequences: the red cross on a white background of the Red Cross emblem, so designed to honour the organisation’s Swiss founder. If the historical connections between Switzerland and this humanitarian symbol are addressed in the interview with Pictet, the location footage is full of potential to ironize his words.

The flags reveal the real concern of the Geneva footage, which is to address the wartime failure of the ICRC to assist the Jewish victims of Nazism or to protest on their behalf. Pictet describes his role as the author of a public ‘appeal’ in October 1942 that was never issued, and the ICRC’s acceding to German refusals to provide information about ‘racial’ prisoners. In the present, Pictet insists that he only learnt about the ‘exterminations’ in 1943, a year later than Lanzmann claims must have been the case. The concluding reel to the Geneva sequence shows the Committee’s headquarters, the camera’s focus on the prominent Red Cross flag allowing the mise-en-scene to augment the interview’s ‘exposure’ of the ICRC’s shortcomings (Cazenave 2019: 221).

Despite the absence of traces of the wartime past in Switzerland, which, as Pictet reminds Lanzmann, was ‘encircled’ by Nazi-occupied countries but never invaded, the setting of the interview in his office at the ICRC headquarters implies the unity of past and present. Following the pattern of the interview in Shoah with Jan Karski, which is crosscut with imagery of New York, we can imagine this footage being edited so that Pictet’s words are heard over sequences of Geneva, including the fittingly impenetrable fortress of Rolle Castle as well as the lake and public buildings, as if we are looking out of the window while he speaks.

In Karski’s case, it is the Statue of Liberty as a beacon of freedom which constitutes a bleak visual counterpoint to the former Polish envoy’s describing the difficulty of provoking a response from the American government to his eyewitness report on mass murder; here, it is the Red Cross flag that is a reminder, exaggerated by Pictet’s defence, of the ICRC’s catastrophic failure to live up to its promise.

Lanzmann’s words about the Nazis’ ‘making fun’ of the Red Cross emblem bring the disavowed detail of mass murder into the room. He cites an example of the Nazis’ cynical deceptions at Auschwitz, where ‘the containers of Zyklon B gas … were transported in trucks marked with the logo of the Red Cross’, while in Treblinka, arrivals at the camp were killed in the ‘Lazarett’, falsely named as if it were a hospital and marked with ‘a large red cross’.

Although Lanzmann rightly describes this as a ‘dark parody’, what he calls the ‘moral authority’ of the Red Cross flag was also, the outtakes imply, compromised by the behaviour of the ICRC itself. A montage of the two versions of the flag as seen in this footage, that of the Swiss symbol and the humanitarian emblem, could accompany Lanzmann’s words here to emphasize that, whether it is considered nationally or internationally, the failure to rescue was the same. In a final moment without an image-track, Pictet, unaware that the audio recording is continuing, speaks more informally about his concern for the way in which the interview might be edited for release: ‘with excerpts, you can hang anyone'. Yet Pictet, interviewed against a backdrop of the city after which the Geneva Conventions were named, has already condemned himself.

Hôtel Royal, Evian-les-Bains

Evian was the site of a conference in 1938 called by President Roosevelt to deal with the issue of prospective Jewish refugees from German territory, soon after the Anschluss between Germany and Austria. Little came out of it, however, and almost no country offered to increase its refugee quota or to change the common demand for immigrants suited to ‘agricultural’ rather than ‘urban’ living (Afoumado 2018).

In the process of making Shoah, Lanzmann discussed the conference with a number of interviewees, and filmed its venue: the Hôtel Royal, Evian-les-Bains in France. Three shots of five minutes in total were taken by a static camera. In them we see the hotel’s east side in the early evening, the sun not yet set behind it, but lights illuminated on the ground floor and in two upper storey rooms, with a figure moving back and forth in one of them. The wind stirs the trees slightly and eventually catches two flags on the roof, revealing one to be a Stars and Stripes and another a French tricolour.

Even in such minimal material there are details that could be used to evoke the conference. A figure walking back and forth in a room would stand quite fittingly for a frustrated observer at the conference, such as Nahum Goldmann of the World Jewish Congress (and the first person Lanzmann interviewed for Shoah), or maybe even the American delegate Myron Taylor (although he actually took a room on the other side of the building). The flags on the roof could be used to prompt thoughts about how the countries they represent made little effort to deal with the refugee problems. Or they could indicate the international nature of hotels, and the different nationalities of guests. People of different nations are away from home, and yet have recognisable and recognised nationalities. In the context of the conference, this could be contrasted ironically with the situation of Jewish refugees who were restricted by national borders, had been stripped of German citizenship and would have their passports stamped with a J three months later (in October 1938) – a German solution to Swiss demands articulated by the Federal Police Chief Heinrich Rothmund (the primary Swiss delegate at Evian).

Voices from elsewhere in the outtakes could be played over this footage. Henry Feingold talks of Evian as a ploy from Roosevelt to seduce Jewish American voters. Nahum Goldmann describes it as a ‘terrible conference’ in which everyone found some excuse why they could not take in a single Jew and all he did was learn geography. Richard Rubenstein says that it was a ‘way of appearing to act, whereas in fact one wasn’t acting’. The very fact that there is so little to see might be used to indicate that so little actually happened.

Indeed, the dearth of things to observe might allow us to think about the film as much as the hotel as a ‘site of memory’. These outtakes have been sitting for forty years in an archive – more or less the same gap in time as that between the conference itself and the point when filming was carried out. The work undertaken by Lanzmann and his team has become a historical event in itself – marked not least by the shift in French public discourse from ‘l’Holocauste’ to ‘la Shoah’.

The matter of the film that they used registers this moment of filming. In their current online form, we see many features that would have been edited out as imperfections if they had been used in Shoah itself. Many reels have been digitized to include the leaders at their heads and tails: monochrome frames often of a burnt orange colour. In interviews, recorded sound sometimes plays over these parts, and in other films created from the outtakes (e.g. the USHMM’s own Shoah: The Unseen Interviews), such moments are included.

In a later film by Lanzmann, The Last of the Unjust (2013), different times of filming are signified by the different kinds of frame he uses. Footage of an interview from the 1970s appears in a narrower aspect ratio with black bars on either side. More recent footage of Lanzmann revisiting the site of Theresienstadt uses a wider aspect.

Working to a similar logic, frames from the leaders could be incorporated into a film about Switzerland and Evian, for example as background for explanatory text. Other features of the film stock itself – scratches in the celluloid or fluff in the gate – might be left in rather than cleaned up, to trigger ways of thinking about how the past comes into the present.

These different ways of approaching making the present film would also take into account Shoah’s form being a result of its subject: a film that essentially meditates on the moments before (mass) death. Questions of rescue and refugees were ones that Lanzmann decided to leave out. Outtakes dealing with these issues might, therefore, need to be edited together into a film in a different form. As we have suggested, techniques for so doing could include synchronizing the soundtrack with imagery for maximum contrast in ways that are only implied by the outtake reels as they stand; by adding dialogue drawn from elsewhere in the outtakes; or even using generic sound effects, such as those of water lapping or flags whipping in the wind, to draw attention to these features and their understated but crucial meaning for a filmic consideration of the failures of wartime rescue.

References

The outtakes were created by Claude Lanzmann during the filming of Shoah and are used and cited by permission of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Jerusalem.

Afoumado, Diane, 2018, Indésirables: 1938: La Conférence d’Evian et les réfugiés juifs, Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

Augé, Marc, 1995 [1992], Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Super-Modernity, trans. John Howe, London: Verso.

Cazenave, Jennifer, 2019, An Archive of the Catastrophe: The Unused Footage of Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’, Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Lanzmann, Claude, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Shoah Collection, 1978-9:

‘Interview with Henry Feingold’, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004817

‘Interview with Jean Pictet’, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004811

‘Interview with Nahum Goldmann,’ https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1005212

‘Interview with Richard Rubenstein’, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004819

‘Shots of Locations, Germany and Switzerland’, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1005206

Lanzmann, Claude, 1985, Shoah, France: Les Films Aleph

Lanzmann, Claude, 1997, A Visitor from the Living, France: Les Films Aleph

Lanzmann, Claude, 2013, The Last of the Unjust, France: Les Films Aleph

USHMM, ‘The Evian Conference’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-evian-conference