By Dr James Jordan

When liberation footage was first shown in American cinemas in the spring of 1945, the graphic images were accompanied with commentaries that reflected an uncertainty over how one should use and respond. Some demanded that the viewer look and be active, while others suggested that the only response would be to look away. As has been noted elsewhere, what was clear was that these images were being constructed as morally imperative and simultaneously repugnant and compelling. It has also long been argued that the images themselves were problematic because their context was not explained correctly and they presented the prisoners as less than human. Omer Bartov is one of several critics to have commented that this continues to be the case and that when used, liberation footage ‘inevitably represent[s] the victims as horribly emaciated, only quasi-human creatures, and if they express sympathy for the human debris of Nazi racial policies, they do not arouse empathy’. In other words, the films continually fail to explain the crimes on display or to engender any understanding of who was being murdered, with criticisms being particularly widespread in respect of the identification of the victims, often obscuring the particularity of the Nazi treatment of the Jews as a group. But in some respects it can be argued that the above does not matter because these images are about shocking the viewer and demonising the perpetrators rather than offering any understanding of who the victims were or the complexity of what is being seen.

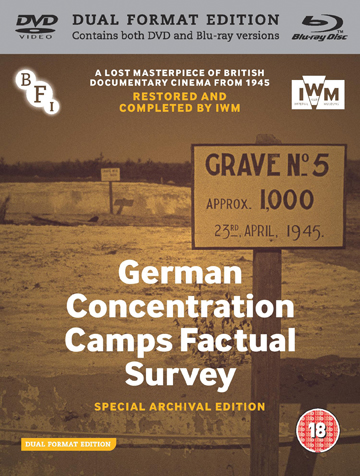

Liberation images have continued to divide audiences and have been questioned as sources for classrooms and as films in their own right. For some, these images are the catalyst for questioning and the road to understanding, meaning that they should continue to be shown because they have an emotional and pedagogic value. And yet for others the images are too problematic, not only because of the content needs to be explained more carefully than is always possible, but because the meaning changes according to context. The political complexity of this on a national level was brought to the fore in Andre Singer’s Night Will Fall (2014), a documentary film that recounted the story of the making of a British government documentary known as German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (1945) that used images of liberation as evidence of German guilt. It was a film that was never finished as the advent of the Cold War meant the embracing of the Germans as allies, making a film that demonstrated German guilt politically problematic. An incomplete version of the film was made in 1985 but it was not until 2015 that German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was finally completed and given a general cinematic release. Now, two years on, it has a Blu-ray/DVD release and the result is a film that documents the horror of the camps and celebrates the work of the original filmmakers and the remarkable efforts of the restoration team. It is also a film that comes with many valuable extras, all of which make it essential viewing in the classroom, albeit only with certain caveats.

I first used the incomplete film – The Memory of the Camps (1985) – for my teaching in 2004, for a module on the Holocaust and film. Cautious of the need to provide context, I presented a battered video copy alongside Elizabeth Sussex’s excellent summary of the film’s history from Sight & Sound, and an old recording of A Painful Reminder (1985), the documentary on the film’s origins which would be re-told and expanded upon by Singer 30 years on. The module was a brilliant experience that taught me much, not least the power of liberation footage and the need to use that material carefully and respectfully. Now that we have at long last a fully restored and finally completed version of the film, the need to use these images thoughtfully seems more pressing than ever.

The film itself is compelling and gruesome. The opening titles, created specially for this version, are modelled on the documentary The True Glory (1945). This is not the only intertextual referencing though, for this damning condemnation of the Nazis opens with scenes taken from The Triumph of the Will (1935) demonstrating the power of both the camera and Hitler as he addresses the party faithful and adoring public. From this moment of celebration the tone of the film changes: the crowds of the living are replaced with the bodies of the dead and dying found by the British troops at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen in April 1945, only ten years on, but a lifetime away for so many.

Image © Imperial War Museum.

The prominence of Belsen in this British production is logical and powerful, albeit a choice which may appear less obvious for a younger audience for whom Auschwitz is perhaps the on name which resonates as a site. And yet one is struck by just how familiar so many of these images are, images seen with such regularity in films, museums and exhibitions. These familiar images include the living, the dead, and the dying. It is the living who are the focus of the first shots, but this is lost quickly as they are replaced by the dead. It is hard to watch, not least because the living, the dead and the dying are not too dissimilar here at times, and the struggle of the emaciated prisoners is as horrific to witness as the gross spectacle of the bodies of the dead: it is the ongoing pain of the living and the dying which is perhaps most evident here.

The film was originally intended to be used as evidence and it is clear that what one sees is a crime scene, showing both the bodies of the murdered victims and the accused. But while what we do not see here is perpetration – liberation only ever shows the aftermath – we do see the perpetrators. The camera captures the SS and German soldiers labouring, placing bodies on trucks and burying the dead in the mass graves that would soon be covered with grass, something that would not be forgotten by the Jewish memorial unveiled at the camp one year on, with its inscription: ‘Earth conceal not the blood shed on thee.’

In addition to this documentation of the perpetrators, there are shots of bystanders and liberators, with the film deliberately edited and narrated in a way so as to counter suggestions of denial. The film highlights questions of guilt and complicity, and also gender issues in the camps, identifying both men and women as victims and perpetrators. They are also there as bystanders and a commentary notes that the film contains a good deal of anger, a point powerfully made by the inclusion of names of the locals and perpetrators in the shot list.

Image © Imperial War Museum.

There is, as has been widely noted, an absence of the use of the word Jew in the script, but it is present, reflecting the contemporary view that Jews were not to be singled out but rather presented as one of many groups of people to be persecuted, with the film’s narrative picking up more on national identity. But the restoration means that for the first time one can clearly see Leslie Hardiman and the star of David on his cap as the script intones: ‘And so they lie – Jews, Lutherans and Catholics.’ The references are there and the film becomes testament to the confusions and what was still yet to be understood in 1945. For that reason the factual errors of the film are allowed to stand, and rightly so for this is, as the introduction makes clear, ‘an important historical document’ that ‘has been restored, not revised or updated’.

One of the most moving scenes involves children liberated from Belsen, their plight articulated by the commentator’s question: ‘Where are their parents?’ Almost certainly they were not in the UK as the British government failed to provide refuge. The restored version of the film ends with the warning that ‘unless the world learns the lessons these pictures teach night will fall. But by God’s grace, we who live will learn.’ But when we continue to deny refuge to asylum seekers, what have we learnt? And if a film needs to teach us, then have we missed the point? And yet this is a film of tremendous value and importance, one that will be used at universities to educate for many years to come.

About the Author:

Dr James Jordan is a Karten Lecturer, Parkes Institute for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations in English at the University of Southampton. He went to Southampton in 1994 as an undergraduate in English and History. An MA in Jewish History and Culture was followed by a PhD entitled Bearing Witness to the Holocaust in the Courtroom of American Fictive Film. In 2005-6 he worked as Teaching Fellow in Jewish Fictions and Modernism at Southampton. He subsequently held the Ian Karten Research Fellowship, a five-year post within English under the auspices of the Parkes Institute for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations, before becoming the Karten Lecturer for the Parkes Institute. He is also co-editor of Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History.