by Ian Greaves

Nigel Finch was an instrumental and transformative presence across the first two decades of Arena, from the pilot edition in 1975 through to his death from an Aids-related illness on Valentine's Day 1995. Here, Ian Greaves looks back on the director and co-series-editor’s life and work.

It is 20 September 1973, and at London Weekend Television studios Lord Clark is rehearsing his latest talk about the Mona Lisa for the cameras. Clark was an art historian and great populariser; a key figure in the post-war demystification of art for the masses. Not least, he had paved the way for television’s approach to this vast subject. Today he is a guest on Humphrey Burton’s Aquarius series, and unbeknownst to Clark a young researcher has been quietly fiddling with the script during the lunch break. In colleague Judy Marle’s telling the autocue rehearsal is brought to a juddering halt with just three words: ‘Who wrote this?’ Through an icy studio atmosphere the researcher emerges, makes his confession to Clark and is chastened by the experience.

That researcher was Nigel Finch. Already he has shaped a distinctive film for LWT about Stanley Spencer (1972), bending the usual grammar of documentary, and now, with the Mona Lisa, he is attempting to find infinite means to animate through graphics and visual effect an unavoidably static and quite lengthy talk about a single work of art. The plan does not quite come off, and indeed earns him a reprimand from the guest, but it nonetheless demonstrates a new-generation zeal and an editorial sensibility that will go on to spark many more fires.

Nigel Finch

At Finch’s memorial service in 1995, Alan Yentob described him as a person possessed with ‘a passionate, exuberant intelligence.' This was always evident. He was born in Tenterden, Kent, in 1949, and became a star student at Bromley Grammar School for Boys, completing his A-Levels early. The camera soon became an extension of his personality: Finch’s teenage film Other People won the SEFT Young Filmmaker of the Year Award in 1967.

An interest in film continued throughout his time at the University of Sussex - where he studied art history - but this did not necessarily indicate a progression to the small or big screen. His particular fascination was with audiovisual education - which he specialised in during teacher training at Brighton Polytechnic - using aural and pictorial methods such as slide projection to assist learning. A life working with young people through these aids appeared to be his calling. By misadventure, however, Finch landed a dispiriting placement as a teacher in Wolverhampton where the routines of a steady job proved incompatible with his drive. In desperation he wrote to Humphrey Burton at LWT, who rescued this young man of 22 and transported him into television at the end of 1971 on a £23 per week contract.

The path to Arena, a series which Finch strongly helped to define, was not an obvious one. There were detours into researching for David Frost, including a film about Darlington F.C., then to the children’s department at BBC Television where he contributed to series one of Why Don’t You..?, John Craven’s Search and Valerie Singleton’s chat show. The latter afforded him the opportunity to direct professionally for the first time.

By June 1975, Humphrey Burton had returned to the BBC as head of the Music and Arts department and quickly commissioned a new topical arts magazine - not a million miles from Aquarius, and one that could be a little more niche than Omnibus. This was Arena, onto which Finch was almost immediately hired as a director. His specialism was used for the Art and Design sub-strand, to which he delivered shorts about Andrew Logan, Chris Orr, and Boyd & Evans amongst others. All visually strong, cheeky, and suffused with a deep knowledge of art. This positioned him well on the London scene, and rare was the gallery opening that failed to feature Finch on the guestlist.

The character of his films was already one apart. They eschewed a presenter, which was not in itself unusual, but did provide deliberate and extensive space for a melding of director and artist. Almost fitting at times to describe this as art about art; they were works in themselves – sympathetic, collaborative, and self-expressive. Finch tended to resist the John Read tradition of artists giving a series of statements in voiceover as they toiled at the canvas. Invariably, he took them out into the world to find visual metaphor and chance action.

As Finch wrote in Art Monthly, 'in a world of minority viewing, Arena [at this time] was so minority that it didn’t even register on the audience survey. So Arena changed course.' In 1979 it rejected topicality and put its faith in the passions of its producers, be it Nigel Williams on theatre and literature, Gavin Millar on film, or Nigel Finch on just about anything. Benefiting from the ‘cushion effect’ of the BBC's extensive arts output, Arena was free to follow its own 'frequently idiosyncratic vision of the arts.’

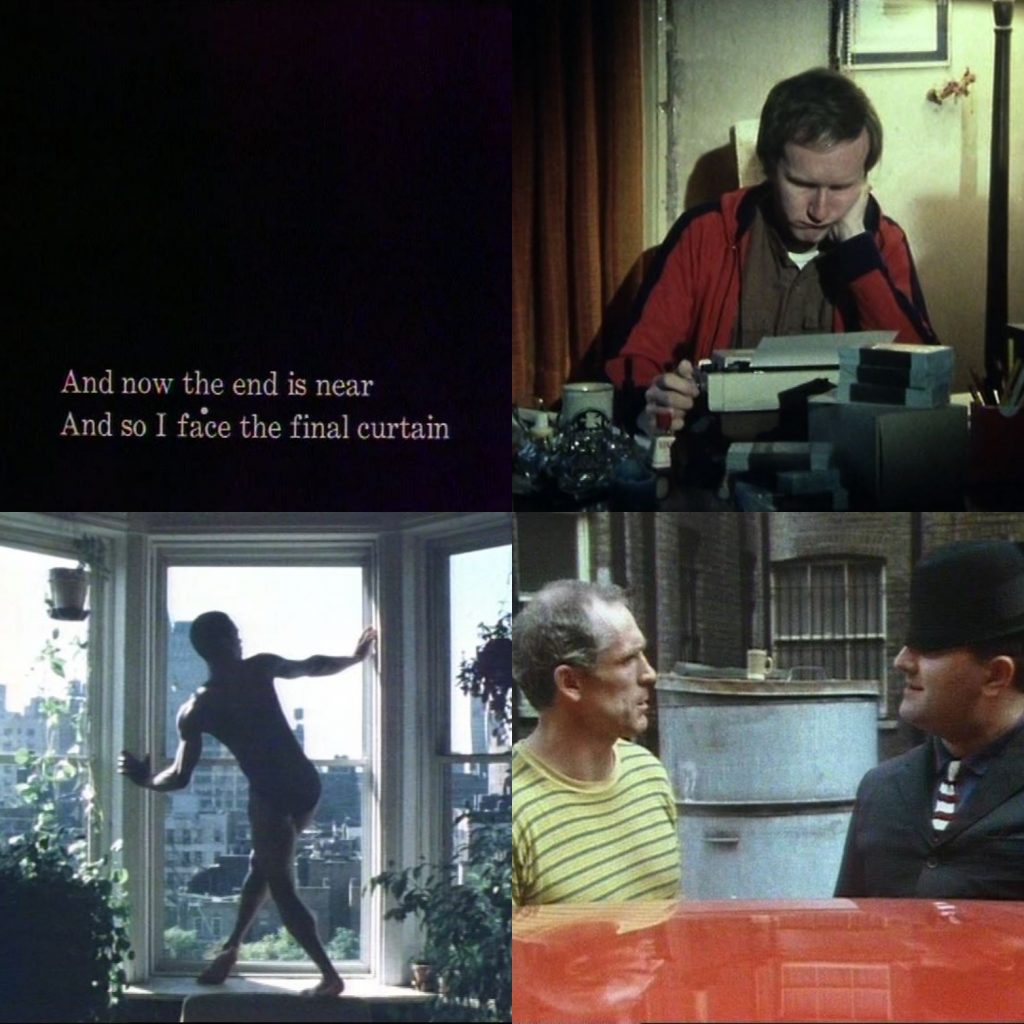

The working relationship between Finch and recent arrival Anthony Wall - then a researcher - was key to the strand developing a distinctive identity under series editor Alan Yentob. My Way (1979) - from Wall’s initial idea - was a short film that took on a life of its own, the commission expanding to full-length as the duo dug ever deeper into the peculiar popularity of the song. Climb Every Mountain (1980), a study of failure from Eurovision through to politics, followed, but it was with Chelsea Hotel (1981) and The Private Life of the Ford Cortina (1982) that ambition matched formal experimentation. Through its fractured day-in-the-life approach, the New York film embraces chance and scale. The 1982 entry meanwhile elevates popular design to an art form, whilst colliding together myriad approaches to documentary in a restless and witty manner. It even includes a song. As Finch later wrote, ‘I became interested in dealing with the visual arts in an oblique way, bringing them into other subjects.’

Stills from four Arena films, clockwise from left: My Way (1979), Climb Every Mountain – Or, Nothing Succeeds Like Failure (1980), Chelsea Hotel (1981), The Private Life of the Ford Cortina (1982).

The title sequence, which had been introduced for the 103rd edition of Arena on 8 January 1979, is another defining moment. Strands can survive on a strong editorial line and a talented group of producers, but few last without a ‘signature’. Think of Monitor, the South Bank Show or Play for Today for examples of expressive titles - and theme tunes - that exude confidence and elicit a degree of trust from their audience. Wall to this day refers to the 'pre-bottle' and 'post-bottle' eras of Arena, which demonstrates how defining this moment was. David Wheatley took the shot, but the key concept was Finch's.

Arena opening titles

Throughout the 1980s Finch was keen to explore ‘performance’ from different perspectives and interrogate how best to relate this to documentary. In music, this ranged from an exhausted Dire Straits (1980) recovering from a tour, to 1989’s feature-length profile of the Rolling Stones’ high-energy globe-trotting machine. For Finch’s study of Kurt Vonnegut (1983) the novelist’s characters come to life and interact with the real world. Meanwhile, in The Caravaggio Conspiracy (1984) - a film which is itself about fakery - we see audacious experiments in dramatised reconstruction. As Finch flexes every new creative muscle, his work grows richer. By the time of Ligmalion (1985) - where a fictional character is inserted into London’s nightlife and ‘ligger’ culture - it is at times hard to say where documentary ends and fantasy begins.

The Music & Arts department was a troubled beast by 1985, though morale was improved by the appointment of Yentob as its head. (Finch is rumoured to have invented the nickname ‘Botney’, still used to this day.) It also prompted change at Arena, with Finch and Wall becoming joint series editors - an unusual arrangement that reflected the scale of work involved. The output of the series was extraordinary in this period, a typical year generating 25 Arena films, 14 editions of spin-off series Rhythms of the World, and a theme night - a concept that in its modern sense was more or less invented by Arena. Finch would lead on one half of this work, Wall the other, but a unity of attitude remained.

Together they were formidable. Journalists would encounter a pair who finished each other's sentences. Directors complained of them conspiring to give the same feedback on a film, but more often it was that they simply thought the same way. Anthony Wall recalls that ‘Nigel and I would never enter a room together without being completely fearless. We would always outflank the opposition.’ The sixth floor regarded them with intense suspicion, but they kept winning awards.

Despite the considerable workload, Finch was keen to develop elsewhere. He was encouraged by producer Ruth Caleb, who gave him the chance to direct Screen One docudrama Shergar (1986), swiftly followed by the purely fictional and non-naturalistic Raspberry Ripple (1987) which he developed with his partner Rupert Haselden. This experience with fiction would feed back into Arena, including the period drama John Daniel the First (1989; another Haselden script), and The Other Graham Greene (1989) which, as Finch’s notebooks suggest, was one of the most difficult concepts of all. He wrote to Greene: ‘This curious Chinese puzzle is increasingly turning into an essay on the nature of truth - is a fictional documentary a contradiction in terms?’

Finch and Haselden were both diagnosed HIV+ in 1990. Rather than leave him defeated, this galvanised Finch to prioritise the projects he most wanted to pursue. Partly on Haselden’s encouragement and as a positive statement against the scourge of Aids, he became a visible gay filmmaker tackling LGBT+ subjects, where previously his bisexuality - for want of any easy word to describe him - had flown under the radar of most colleagues and viewers.

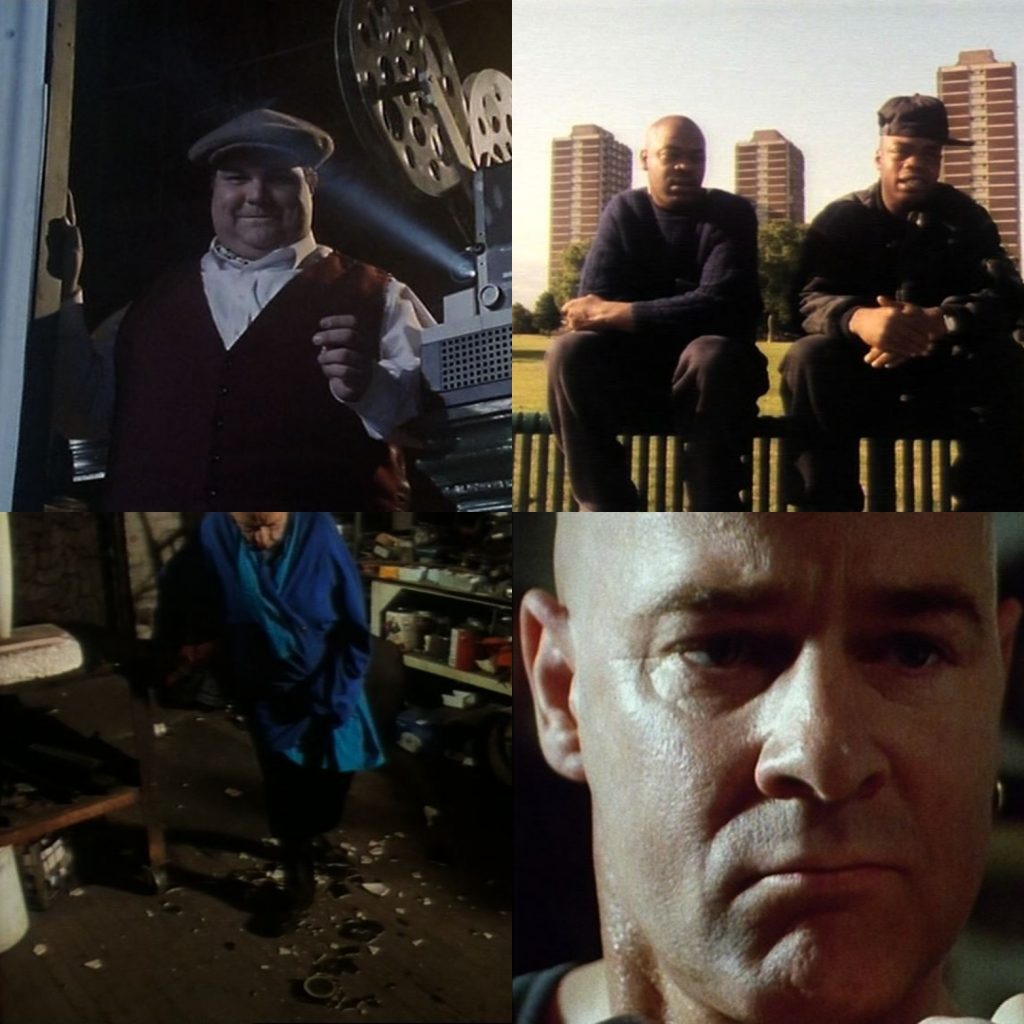

A glorious five years of increasingly wild work followed. For Arena this included the film fakery and huge set-pieces of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (1991), a valuable guerilla short about pirate radio (Pirates, 1993), the unforgettable meeting with a combative Louise Bourgeois (1994; objects flew), and The Ring - A South London Tale (1994), a severely underrated Video Diaries-style meta-documentary of constructed reality that was critically trashed at the time but ought now to be recognised as the forward-thinking Arena classic that it is.

Stills from four Arena films, clockwise from left: Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (1991), Pirates (1993), Louise Bourgeois (1994), The Ring – A South London Tale (1994).

In television more widely, Finch won the Prix Italia for his five-part opera-for-television The Vampyr (1993) and, earlier, provoked controversy with his powerful Screen Two adaptation of David Leavitt’s The Lost Language of Cranes (1991). Howard Schuman recalls Finch confiding around this time that ‘If I don’t make films, no one will remember me.’ It is certainly true that Cranes is one of his most lasting and remembered pieces, in part due to its availability on DVD on both sides of the Atlantic.

Rupert Haselden died, having developed Aids, in May 1994. Despite facing the same fate, Finch saw his final Arena film greenlit three months later. This was a free dramatisation of the events leading up to the Stonewall Riots, with scarcely any documentary element to it and to all intents and purposes a feature film. The shoot began on 27 October and lasted six weeks, which the BBC knew to be a huge gamble on health grounds - but the respect for Finch ensured that it happened. ‘He was driven and wanted to make that film,’ says Wall, and producer Christine Vachon recalls an absolute commitment on set, even to the point of collapse when the debilitating effects of a brain virus (Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy) took hold. Finch ‘died with his boots on’, overseeing the edit at his home during an extraordinary few weeks in the winter of 1995. No one who visited will ever forget it.

The danger with assessing any long-running television series or strand is the loss of the voices of those who have died and therefore cannot tell their story. There is no such risk with Finch, who is intensely remembered and loved by a great many colleagues, all keen to speak of a force of nature whose laughter and love for life was truly infectious. Arena's 40th anniversary party was held at his former home in Balham, and a Trust continues in his name. It is hoped that more can be done to celebrate his films, for Finch is one of the essential, elemental figures in the BBC's formidable history of arts documentaries.

About the Author

Ian Greaves is an independent researcher specialising in British television and theatre. His major books include edited collections of the work of Dennis Potter (2015) and Dr Jonathan Miller (2017), and for Radio 4 he has devised programmes about Douglas Adams and Dudley Moore. For television, Ian was consultant on Drama Out of Crisis: A Celebration of Play for Today (2020). He is currently researching the history of arts television.