by Travis Wagner

Jack Webb’s cult account of ‘true crimes’ The Badge: The Inside Story of One of America’s Great Police Departments provides an imagined officer’s opinion on home burglary. The officer describes burgled houses having “not been forcibly entered--not a screen cut, a door forced, or a lock broken--and most of the victims had been lonely defenseless women.” (6).

Webb’s pop culture variation of a cop “carrying a badge” matters as his popular show Dragnet argued anybody who gets out of line with normative performances of citizenship should face punishment for their crimes and commit to "protecting the names of those who are innocent." In 2020, Webb's vision of the police force and home protection seems comical. First, the prevalence of home security systems affords self-surveillance. Second, and decidedly less humorous, is the actuality that protecting a home is a privilege afforded nearly exclusively to white people. Countless examples of police entering the homes of people of colour without warrants or with variations of warrants that do not require permission to enter one's home (i.e., "no-knock" warrants) exist—the most startling example of this being the murder of Breonna Taylor on March 13, 2020. The officers responsible for Taylor's murder, to date, received no murder charges, with Officer Brett Hankinson instead receiving a charge of wanton endangerment only for the bullets that hit the walls and homes of others.

Nonetheless, there remains a need to protect homes from burglary. In response, police forces continually create and implement various initiatives within their communities to train both officers and citizens to deter robbery. But orienting one's gaze towards these initiatives renders the naively optimistic good doings of law enforcement questionable. We need not look very far into media history to understand the relationship between police officers, home invasions, and inequities in presumed protections across racial identities to see this. Indeed, reflecting on the non-theatrical film genre of police training films illustrates quite clearly the long-running inequities of some homes as worthy of protection and others as warranting suspicion. Further, this division resolutely exists at the site of race.

The Badge: The Inside Story of One of America’s Great Police Departments, (1958)

Non-theatrical, orphaned works are those whose lack of "commercial interest" leads to their being long-forgotten, often in the corners of a film archive (127). Amongst these works include the police training film, an incredibly complex media form residing somewhere on the spectrum of the educational film concerned with how to "teach, inform, [and] instruct" (Orgeron, Orgeron, and Streible 9) and corporate films as Patrick Vonderau argues, corporate films desire to promote positive corporate cultures. As such, police training films subtly, if not outrightly, promote positive work done by police officers in the community (60). But how might we interrogate police training films for presumptions about whose identities require protection? Further, what can we learn about the contemporary realities of police bias through the existence of these films, their potential use, and their narrative leanings? To answer this, we turn to a relatively small collection held at the University of South Carolina's Moving Image Research Collection (MIRC).

The collection known as the Spartanburg Police Film Collection came to MIRC in 1997 and represented the training films of the Spartanburg County Police Department. Spartanburg County is roughly a hundred miles from Columbia (South Carolina's capital) and home to just above 300,000 citizens. While no formal collection mission exists for these dozen or so films, their range of content suggests materials for internal and external use by the department. Items include the light-hearted and simple Otto the Auto intended for children to learn traffic safety. There are also more complicated items like The Black Cop (1969) which titularly explores being a black cop working in a predominantly black neighborhood. This film, as I have discussed elsewhere, provides a window into the considerations law enforcement give to their reputation with regards to race relations (Wagner and Cooper, 2019). Such mediated variety suggests two things. First, police training films' themes range from incredibly general to specific police work praxis. Second many films carried an expectation of being screened to the community to remind them to obey traffic laws or, in more dated films, guide women on how to be less susceptible to rape through clothing choices.

The films show police officers how to perform their duties better and, in turn, suggests how citizens can prevent crime. However, an exception exists when it comes to more predatory crimes wherein the victims make themselves candidates for attackers by personal choices or ignorance. The victim-blaming components in these films cannot be understated. Such films are troubling, if sadly all too familiar, through a contemporary lens, but even these examples exist in public. The home, alternatively, is a private space, which can come under attack by burglars.

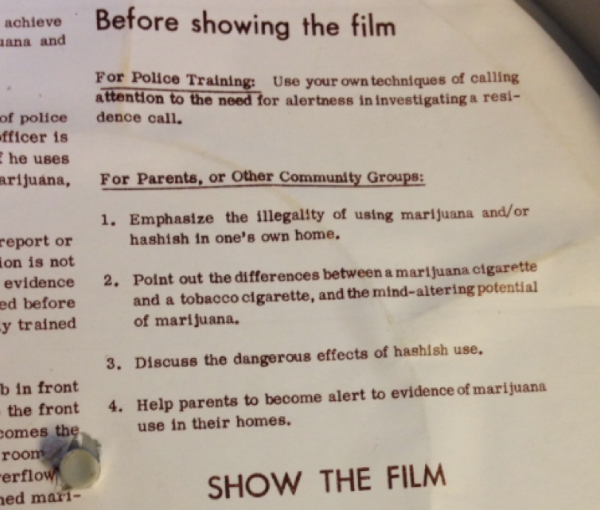

Regarding private space, two films from the Spartanburg Police Film Collection stand out. Use Your Eyes (Residence Investigation) and Crime in the Home. 1970’s Use Your Eyes (Residence Investigation) produced by Film Distributors International describes “how to recognize evidence of marijuana or hashish use in a residential investigation.” It is also worth noting that is expressly called a “a police training film” in its description. The inside of the film can include guidelines for post screen discussions either with officers or concerned parents.

Group discussion prompts found on the inside of the film canister for Use Your Eyes (1970)

The second film Crime in the Home, a 1973 production from Macko Productions, "uses vignettes to demonstrate effective ways of self-protection in the home." As Webb reminds us, a home invasion happens to those who allow the burglar easy access to their home. Attendant to this, Crime in the Home, suggests feigning occupancy to deter robbery. As the film tells, even these preventative measures are no match for the more precise burglar detection. According to this film, prevention comes through installing an alarm system, adding a peephole. Here ensuring protection falls upon the resident asking them to change their private space to make it less ideal for a robber. In Crime in the Home rhetoric surrounding the act of robbery, the absolute most straightforward way to prevent burglary is for citizens to arm their homes like fortresses, creating a sense of private impenetrability that is internalised and understood social performance. To get robbed requires being susceptible to the act, and as Crime in the Home would have us believe only happens when persons lay down their guard in any way. Of course, creating a haven of private safety that is impregnable comes with various presumptions about access and disregards how gender, race, and class might problematise these notions. Tellingly, Use Your Eyes illuminates the perceived free reign possessed by law enforcement.

Played out as an example of how an officer might partake in an investigation for possession of hashish or marijuana, Use Your Eyes focuses only briefly on officers outside a home, talking momentarily to an occupant (what appears to be a white woman) who opens her door and without question allows an officer into the home. Such willingness to allow a person into your residence expressly contradicts the advice of Crime in the Home. According to experts interviewed in this training film, all persons require thorough vetting before entering a home. Still, for Use Your Eyes, the police circumvent such caution through unchecked authority. To emphasise this, Use Your Eyes deploys point of view shots that slowly morph a room into an active "piece of investigation." At this moment, the home becomes foreign, filling with "information that is not clear" and in need of “specially trained eyes" to spot illegal substances. The narrative eyes then match an extreme close up of the primary officer's eyes as they survey the room.

The surveilling gaze of the unnamed officer in Use Your Eyes (1970)

As the film is about a criminal investigation, the home items also become subject to search and seizure; criminal possibilities eclipse any private property notion. While this is not a film expressly about a home invasion, its concern with public safety dismisses self-protection and privacy to address presumed illegality. Composed with only a figure of a drug user who occasionally appears, the intercut eyes evoke an almost panoptic gaze about the house, with Webb's notion of police authority weaving disconcertingly with Foucauldian concepts of surveillance. Use Your Eyes extends this detachment of the private home further with terminology like "place of residence." The film's insistent, frigid legality continues by removing persons and non-drug objects from the space, making it and everything within it inhumane in the process.

In contrast, Crime in the Home operates much like John M. MacDonald's burglary study from the same era titled Burglary and Theft. Both the film and book aim to lower the costs of a burglary, which are, according to MacDonald "impossible to estimate" as they mean "higher premiums for burglary insurance," "costs in public utilities," and, of course, "taxpayer money" (3). MacDonald explains that a well-protected home could deter attacks and save money. Taking a liberal definition of home, Crime in the Home aims to show everything from the dangers faced by a family being attacked by a robber, tellingly portrayed as a person of colour, to also showing a woman living alone whose willingness to allow a charming young man into her home leads to her demise. Throughout the narrative, various experts (law enforcement and former professional burglars) discuss both the well-secured home and one inviting invasion. Consistent with other police training films, the film places blame on victims for their breachable homes. MacDonald accordingly asserts that homes can be less inviting by "not advertis[ing] their absence." Simply put, home security is best prevented by always being home.

However, even actual physical occupancy can be tricky. An initial interaction between an officer and a woman of colour in Crime in the Home notes not only her willingness to answer a door (a stark contrast to the beginning of Use Your Eyes) but also her failure to provide her house with adequate protection, whether by installing a peephole or choosing reliable locks. Her is used in the singular here because one of the many complications in the narrative of Crime in the Home is the presumption that women in charge are somehow more susceptible to two things: attacks by perpetrators and singledom. Further, a complete family is shown within Crime in the Home as nuclear, white, and heterosexual (a family facing an impending burglary by a black male no less). The home is private, but only in favor of patriarchy and whiteness. The only two times when white males in the home space appear, it is as misguided, with one trying to take the act of gun-based protection into their own hands and the other refusing to leave a light on in fear of a high energy bill. So while the film does not outright suggest this, one could argue that part of a "properly" protected home is a white male's presence.

At this point, one can find the glaring issues at play within the Spartanburg Police Film Collection. While not as overtly racist as some of the "how to deal with a person of colour on your police force" films and certainly not as offensive as the victim-blaming rape prevention films of the same era, Crime in the Home does treat any degree of otherness as susceptible to ignorance. In line with intersectionality tenets, a person's household becomes equally oppressed or privileged contingent on how far from a spectrum of white, male wealth they exist. Further white masculinity stands in for policing. The cop's suggestion that one should leave lights on or install multiple locks assumes that one knows how to do so, knows who to contact, has the means to pay or retrieve such materials. More importantly, it implies that society and police treat all persons equally. As the murder of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Daniel Prude, Rayshard Brooks, and many, many other people of colour by police have shown, this is hardly a reality today and was certainly not the case upon the release of these films. In the white cop's vision, every homeowner would perform these preventative measures and know-how to deploy appropriate caution when allowing persons into their home. However, these films cannot, or choose not to imagine that the violent perpetrators could ever be police officers themselves.

Between the two films, property and one's home exist in the tension between the right to privacy and that which must be made visible for possible criminal ties. Looking back at Use Your Eyes, one can note carefully embedded language concerning the right to legal search and seizure, suggesting that a cop cannot begin to invade the goods of a person's home until they have ground for legal precedence. Use Your Eyes’ use of editing techniques to remove objects from a room non-diegetically correlate to the film's unseen officers eliminating items from a living room in the pursuit of potential criminal activity. Further, upon officers' arrival to the home, no explanation of the suspect's right to enter to home entry by law enforcement occurs. Guilt is assumed, and access is imminent.

In 2020, such a disregard for legal procedure or consent for entrance might read as woefully dated, but the sad truth is that it reads as all too real. Contrast this with a scene in Crime in the Home where an unsuspecting victim shoots a faux attacker. The segment depicts the lack of accuracy in gun use in home protection; setting the experiment within an open field causes yet another layer of assumption about how the homeowner must protect that which is theirs, a vast space of items, valuables, and, of course, their livelihood. Yet when the cops are looking for something to incriminate a person, this space narrows considerably to a single room. While shared intentions are evident across both films, the glaring contradictions in what the home looks like cannot be ignored.

As filmic artefacts of police ideology, the films discussed provide us with a clearer sense of how much systemic racism and presumed power lie dormant within policing. Sadly, for many people of privilege, such presumptions remain irrelevant to their daily lives. As we find ourselves sitting in our homes for what has seemed like an eternity rarely do, we think about what it means for our home to be compromised. Our current collective safety comes in isolation and social distancing. However, even this assumes that we all have access to home safety in equal measure. So even as Jack Webb wants us to imagine that any law enforcement officer is inherently out to help, the very media produced alongside his popular show about law enforcement tells a different story. If you are a person of colour, cops might recommend that you install a peephole to prevent unwanted illegal intruders, but until the very people tasked with assuring safety follow those rules of home invasion, no home security preventions, minor or major, can be enough.

About The Author

Travis L. Wagner is a Ph.D. Candidate in the School Information Science at the University of South Carolina. Wagner is also an instructor in USC's Women’s and Gender studies department. Their primary research interests include critical information studies, queer archives, and social advocacy in libraries. Their recent publications include articles in Reference Services Review and Open Information Science. They are also the co-creator of the Queer Cola Oral History and Digital Archive.

Works Cited

Macdonald, J. (1980). Burglary and theft. Indiana University Press.

Orgeron, D., Orgeron, M., & Streible, D. (Eds.). (2011). Learning with the lights off: Educational film in the United States. Oxford University Press.

Vonderau, P. and Hediger, V. (2009). Films that work: Industrial film and the productivity of media. Amsterdam University Press.

Wagner, T.L. & Cooper, M.G. (2019). “A new sense of black awareness”? Navigating expectation in The Black Cop. In Field, A.N & Gordon, M., (Eds.), Screening Race in American Nontheatrical Film. Duke University Press, 271-291.

Webb, J. (1958). The badge. Prentice-Hall.