Filmed warfare was a new phenomenon at the time of the First World War and it was months before the British authorities allowed cameramen up to the front line. David Walsh of the Imperial War Museum discusses the restoration of The Battle of the Somme (1916), one of the first such films and long-held to be a classic of its kind.

About the author: David Walsh is Head of Preservation at the Imperial War Museums.

The Battle of the Somme, assembled from footage taken by two cameramen, J B McDowell and Geoffrey Malins, at the time of the opening of The Somme offensive on 1 July 1916, was one of the first official films to be released to the public. This groundbreaking production, a full-length documentary showing activities in forward areas during the build-up and first days of the battle, was immensely successful with a public who had never seen anything of its kind before. Here were actual scenes of the now familiar business of war: the supplies and ammunitions, the troops marching, the big guns, the wounded and the dead. There were even shots, after a carefully orchestrated build-up, of troops going over the top – although this is the one instance where a brief faked sequence is used, as the genuine shots of the first advance are distant and pictorially unimpressive.

When the Imperial War Museum took over the responsibility for the original negative of the film in 1920, it was already in a shabby state – it is one of the laws of film archiving that the more popular and important the film, the worse the condition of the surviving material. The negative was scratched and patched, with a number of inferior quality duplicate sections where the original had been damaged - or perhaps even cut out for other uses. Thanks to the initiative of the head of the Museum’s film collection, Edward Foxen Cooper, master copies of this and many other important films were made on more stable cellulose acetate stock in the early 1930s and it is largely thanks to this pioneering effort that the film survives complete, even though the original negative has long since decomposed.

The 2nd Battalion, Royal Warwickshires marching to the Front: a scene from reel 2, as captured in a frame blow-up from the film in the early 1990s. (image: IWM)

The same scene in a frame-grab from the new version, following restoration work at Dragon Digital Intermediate in 2006. (image: IWM)

And, as with all things today, going digital is the key.

There is a downside to all this, of course. In 1931, there were no special fine-grain duplicating film stocks; neither was there the kind of stringent process control needed in the film laboratory for producing perfect masters. As a result, the master copy of The Battle of the Somme is grainy and contrasty, with a lack of detail both in the shadows and the highlights, and constantly varying exposure levels – all this in addition to the damage and defects faithfully copied from the negative. The challenge to the restorers was to even out the irritating exposure fluctuations, and to try to pull out as much detail as possible from the highlights and shadows. At the same time, the intertitles, badly re-copied in the 1960s, were to be rejuvenated by digitally pasting the existing lettering on to new clean backgrounds.

And, as with all things today, going digital is the key. Where conventional photochemical processes are strictly limited in what they can achieve in film restoration, working on a high resolution scan of the film using all the power of the computer allows the operator to squeeze every drop of pictorial information out of the material, in theory at least: in practice, with some 80,000 individual frames of the film scanned into the workstation, there are problems of scale. Luckily, digital restoration software, designed principally with feature film special effects in mind, can do many things in an automated, or semi-automated, fashion. However, the restorers, Dragon Digital Intermediate, may have begun to regret the day they met the man from the Imperial War Museum when they discovered quite how poorly the automated software actually coped with the film’s particular afflictions. The common problem throughout the film was the way the background detail was ‘bleached’ out, which meant that viewers experienced the film largely as foreground action, with little surrounding context. Enhancing the faint background images whilst leaving the correct balance in the foreground required careful scene by scene judgement from the operator – and then there were the long shots across to the enemy lines: here the details in the shadows and highlights appeared and disappeared as the exposure varied throughout the duration of the shot. After some trials, the restorers realised that the only solution with these shots was to painstakingly manipulate each and every frame by hand to achieve a reasonably smooth shot – an incredibly laborious process.

Fortunately for us, their enthusiasm for the project got the better of vulgar commercial imperatives, and they decided to exceed the original brief by setting to work manually to remove many of the scratches and blemishes which had been printed into the film master and which were beyond the powers of the automated software. The result of these many months of hard work is a startling improvement on anything seen since the film’s original release. At last it is possible to see that a line of marching men are not merely passing in front of the camera, but winding in a huge column into the distance, that shells dimly exploding in a fog are in fact landing across clearly defined enemy lines, and that in the two genuine shots of the actual first attack, men are actually cut down by enemy fire.

Fortunately for us, their enthusiasm for the project got the better of vulgar commercial imperatives, and they decided to exceed the original brief by setting to work manually to remove many of the scratches and blemishes which had been printed into the film master and which were beyond the powers of the automated software. The result of these many months of hard work is a startling improvement on anything seen since the film’s original release. At last it is possible to see that a line of marching men are not merely passing in front of the camera, but winding in a huge column into the distance, that shells dimly exploding in a fog are in fact landing across clearly defined enemy lines, and that in the two genuine shots of the actual first attack, men are actually cut down by enemy fire.

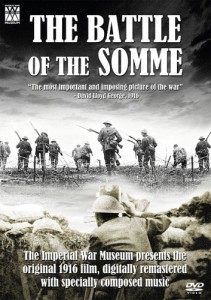

The final restored version of the film has been matched to a fine score for large orchestra specially composed by Laura Rossi, and, for more modest performances, the Museum has even managed to track down all the original sheet music from a list of suggested pieces produced as an aid to cinema pianists at the time of the film’s first release. A DVD release with both sets of music is now available

For further information about the IWM's collection relating to the events, visit: www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-battle-of-the-somme

To accompany the release of its digitally restored DVD edition of The Battle of the Somme, the Imperial War Museum has created a number of free resources, including biographies of the crew, a detailed viewing guide and notes for teachers, all of which are available for download by clicking here.

David Walsh