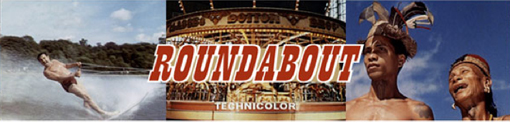

Linda Kaye provides a guided tour of Roundabout (http://bufvc.ac.uk/roundabout), the Technicolor cinemagazine that in the 1960s and 70s helped the government promote Britain as a progressive world leader to South and South-east Asia and which is now available to view online.

About the Author: Linda Kaye is the BUFVC's Research Executive and is resposnsible for the News On Screen web resource and is part of the team behind the Channel 4 and British Film Culture project (www.c4film.co.uk/). Her publications include Projecting Britain: The Guide to British Cinemagazines (2008), co-edited with Emily Crosby.

About the Author: Linda Kaye is the BUFVC's Research Executive and is resposnsible for the News On Screen web resource and is part of the team behind the Channel 4 and British Film Culture project (www.c4film.co.uk/). Her publications include Projecting Britain: The Guide to British Cinemagazines (2008), co-edited with Emily Crosby.

A Free Technicolor Ride through Britain and Asia in 1960s and 1970s One of the most exciting new features to the BUFVC’s News on Screen resource has been the addition, in partnership with the British Film Institute (BFI), of 600 freely available films from the Technicolor cinemagazine Roundabout (1962-1974). The BFI has recently restored this monthly topical news series from the original 35mm elements and the result is truly stunning.

… it was a potent and popular mix that entertained audiences from Cambodia to Korea and Burma to Brunei

Produced by the British government through its Central Office of Information (COI), Roundabout was designed promote Britain as a progressive world leader to South and South-east Asia. Every issue was packed with stories that portrayed Britain in the vanguard of research, the forefront of manufacturing, the driving force of the Commonwealth as well as the creative edge of the arts and design. If the message could be summed up in a single word it would be ‘modern’, the idea being that Asian cinema audiences were presented with a vision of what their future might look like and how Britain was helping her to realise it. Technicolor was a vital element in the transformation of this content within the cinema programme, constructing an important and innovative bridge between the black and white newsreel and colour feature. It lent a gloss to fashion and dynamism to factory lines, imbuing the topical with the glamorous sheen of the fictional. It was a potent and popular mix that entertained audiences from Cambodia to Korea and Burma to Brunei. With its infectious music and spinning carrousel Roundabout’s opening sequence promised a dizzy ten-minute ride around diverse topics and locations seamlessly stitched together by a deft commentary. It constitutes a unique record of Britain and Asia during a period of rapid change and development.

Roundabout was one of a raft of cinemagazines that the COI had been producing since the mid 1950s. This marked the point when the British government fully embraced the necessity of national projection to articulate the transition from Empire to Commonwealth to an international audience. The global potential of television as a transmitter of this ‘soft propaganda’, as civil servants of the time termed it, was recognized and supported by a substantial increase in the COI budget for the next decade. The television stations that gradually emerged across the globe were hungry for content and happy to use freely supplied material, dubbed in the required language. By the time the first issue of Roundabout was released in May 1962, hundreds of stories from series such as Transatlantic Teleview, Dateline Britain, This Week in Britain, Middle East Newspots (Letter from London) and Portrait had already been watched in the United States, Africa, the Middle East and Australia. In the midst of this increasing volume of 16mm black and white material targeted at television stations came Roundabout, a 35mm colour series targeted at cinema audiences.

The origins of this seeming anomaly can be found in a report that Charles Beauclerk of the COI wrote after assessing its Asian operation in 1960. He concluded that the impact of television within this ‘territory’ was minimal and this, coupled with the success of newsreels such as British News in Malaya, led to his main recommendation that a ‘monthly film magazine in colour’ should be produced. Colour would be the means of differentiating their topical product in a regional cinema market with an estimated audience of around twelve million per year. At first the costs were thought to be prohibitive but the Foreign Office agreed to pay for the pilot, which was released in June 1961. Local distributors in Indonesia and Thailand reported a favourable audience reaction and over the next six months Associated British Pathe, a company with an impressive cinemagazine track record, built up a reserve of material.

The first Roundabout issue was released on 1 May 1963 with distribution to Hong Kong, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaya, Borneo and Laos. In addition to English, there were foreign language versions in French, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Thai and Malay. An experimental Chinese Mandarin sub-titled version was made in Hong Kong for testing in Cambodia and there was talk of extending distribution to Burma, Pakistan, India and Ceylon. By the end of the year, the estimated audience for the first issue was around 2 million with an expectation that this would double once distribution was extended to India, Pakistan and Ceylon. This positive reception persuaded the COI to produce two pilots for ‘sister’ productions at the beginning of 1963, Carrousel for Latin America and Parade for all other territories but primarily the West Indies and Africa. All three cinemagazine series would remain in production for another decade, albeit produced by British Movietone from 1969 when Pathe’s cinemagazine unit was closed down.

The format of Roundabout remained consistent throughout the course of its existence. Each monthly issue would contain around six topical stories describing current developments in Britain and Asia. Many British based items would be framed to appeal to Asian audiences by incorporating an official, a visitor or student into the story. For example, the editor of an Indonesian newspaper would visit a Vauxhall car factory (Roundabout 10, February 1963) or a Vietnamese student studying photography would provide the focus for a story on Ealing Technical College (Roundabout 67, December 1967). By the same token, stories based in Asia would include a British element with British machines highlighted in the production of cigarettes in Cambodia (Roundabout 14, June 1963) and Leyland buses centre-stage on the streets of Jakarta (Roundabout 92, January 1970). Sprinkled among the factory lines and research stations were official openings, visiting dignitaries and the occasional dash of royalty. Typical of these are the visit of the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand to Britain & Princess Alexandra to Bangkok (Roundabout 4, August 1962), Prince Sisalumsak of Laos inspecting the construction of the M1 motorway (Roundabout 40, September 1965) and Princess Margaret attending a Commonwealth fashion show (Roundabout 73, June 1968). The resulting mix of stories for an issue was eclectic to say the least, with students studying insurance squeezed in between carpet manufacturing in Scotland and the Lord Mayor’s Show (Roundabout 59, April 1967).

It could be argued that the seeds of Roundabout’s demise were sown in this consistent approach. That it failed to adapt to changing cinema audiences as the impact of television increased but the picture across Asia in 1974, when the last issue was released, is far more complex and contradictory. It is worth remembering that countries such as Sri Lanka, Burma and Laos only established their first television stations between 1979 and 1983. The simple truth was that Roundabout, together with Carrousel and Parade were axed as result of severe budget cuts suffered by the COI and changing priorities with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

What remains is a series that is incredibly easy to watch, as indeed the best ‘soft propaganda’ should be. Although subjects and locations change dramatically every couple of minutes the viewer rarely feels any jarring change. The fact that these diverse topics segue neatly into one another is mainly due to the commentary, often through one word links, supported by the even, sonorous tones of commentators such as Brian Cobby. It is a deceptively simple technique as is the quality of the editing in much of this material. There is an art to telling a story in around 100 seconds and many of the Roundabout items, such as the manufacture of tinsel in Wales (Roundabout 43, December 1965), are a masterclass in how to do just that. Elements of British life that were barely accorded a glance were given a single revolution on Roundabout and transformed into something dynamic, glamorous and often quite beautiful.

Linda Kaye