Jean Painlevé (1902-1989) was one of the pioneers in the development of scientific cinema and was one of its great popularisers. Oliver Gaycken, Assistant Professor at University of Maryland looks at the filmmaker’s life and work

About the author: Oliver Gaycken is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English and a core faculty member of the Film Studies Program at the University of Maryland, College Park. His book manuscript, Devices of Curiosity: Early Cinema and Popular Science, is under contract with Oxford University Press. His articles have appeared in Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television; Science in Context; Journal of Visual Culture; Early Popular Visual Culture, and the collection Learning with the Lights Off.

About the author: Oliver Gaycken is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English and a core faculty member of the Film Studies Program at the University of Maryland, College Park. His book manuscript, Devices of Curiosity: Early Cinema and Popular Science, is under contract with Oxford University Press. His articles have appeared in Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television; Science in Context; Journal of Visual Culture; Early Popular Visual Culture, and the collection Learning with the Lights Off.

A scene from Jean Vigo’s L’atalante (1934) has often struck me as emblematic of Jean Painlevé’s position between the worlds of professional science and the avant-garde. The scene takes place in the barge cabin of Le pére Jules (Michel Simon) as he guides Juliette (Dita Parlo) through his collection of objects that he had amassed during his life of maritime travel. His cabinet of curiosities contains quite a few bizarre and fascinating artifacts, including the nose of a sawfish, a Cuban fan, and photographs from the aftermath of the San Francisco earthquake. The most startling item in this eclectic collection is a jar that contains a pair of human hands. They belonged, pére Jules says, to his best friend.

Painlevé provided these hands for the film, apparently ‘borrowing’ them from a collection to which his scientific career gave him access. Simultaneously a medical specimen and a surrealist objet trouvé, these pickled hands gesture in two directions at once, a tendency that characterizes Painlevé’s films more generally. His film smuggle images from the laboratory into the popular cinema, reinvigorating the cold gaze of objective observation with the spirit of curiosity and wonder.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7PQvkYYikU

Besides being one of Vigo’s best friends (he was at the filmmaker’s deathbed when he died at the age of 29 from tuberculosis), Painlevé was enmeshed in a web of avant-garde connections. He was an acquaintance of Luis Buñuel’s, to whom he showed a film of an actual eye surgery (Buñuel’s response: ‘Do you really believe that just because I cut open an eye in a film that I like that sort of thing? ...operations horrify me. I can’t stand the sight of blood’). He had a working relationship with Georges Bataille, who published Painlevé’s and Eli Lotar’s photographs in Documents, and Lotar would be Painlevé’s cameraman for a brief period in the early 1930s. He spent weekends with Alexander Calder. He enjoyed a brief friendship with Sergei Eisenstein, whom Painlevé helped to smuggle into Switzerland in a basket of dirty laundry in order to see the silent-era film diva Valeska Gert. He was a friend of Man Ray’s, whose L'Etoile de Mer (1928) owes its starfish footage to Painlevé; and he also enjoyed friendships with Pierre Prévert, Jacques Boiffard (Man Ray’s assistant) and told anecdotes about his encounters with André Breton and Antonin Artaud. Another crucial, though unknown, figure is his longtime collaborator and partner, Genèvieve Hamon, daughter of the libertarian anarchists Augustin and Henriette Hamon.

With this circle of friends and acquaintances, it is not surprising that Painlevé is usually associated with the surrealists. In 1924, for instance, Painlevé contributed two short pieces, ‘An Example of Surrealism: The Cinema’ and ‘Neo-Zoological Drama,’ to the first and only issue of Surréalisme, a journal edited by Ivan Goll that included contributions by Guillaume Apollinaire and Robert Delaunay, among others. (This journal is not to be confused, as it sometimes is, with Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, the more influential and longer-lived journal edited by André Breton that first appeared in 1930.) He also filmed vignettes that were projected in Goll’s dadaist/surrealist play Methuselah (1927). And he once used his father’s political influence to spring Andre Breton and other surrealists from jail after one of their provocations—a group assault on a man carrying an umbrella on a cloudy day—resulted in a trip to jail. But he was not to figure prominently in the history of orthodox surrealism, leaving the orbit of Breton in large part because of disagreement over the importance of music. His personality would always contain aspects of surrealism’s provocative, antiauthoritarian tendencies. As late as 1986, for instance, Painlevé said in a Libération interview, ‘I’m very proud that we live in an era that finally recognizes its dependence on shit. All of genetics relies on colon bacilli, which in turn rely on our feces. All experiments are done on it. We’re deep into the shit.’

Jean Painlevé (BFI / Courtesy of Brigitte Berg)

Painlevé’s films elicited enthusiastic responses from artists: his study of skeleton shrimps and sea spiders, Caprella and Pantopoda, which was screened in 1930 at the newly opened Les Miracles theater, caused Fernand Léger to call it the most beautiful ballet he had ever seen, and Marc Chagall praised its ‘incomparable plastic wealth,’ calling it ‘genuine art, without fuss.’ But Painlevé would come into his own not as an avant-garde artist per se; his real achievement lies in his ability to traffic between scientific and avant-garde experimentation. For him the undersea world functioned as an alternate universe whose denizens resembled humans in some respects and diverged radically in others. Painlevé’s regard for his underwater subjects does not result in a collection of cute critters in the Disney mode of anthropomorphism; instead, the creatures he lovingly documents can fill us with equal parts of wonder and admiration as well as terror and disgust.

André Bazin wrote an extraordinary essay that analyzes the aesthetics of science films. Entitled ‘Science Film: Accidental Beauty,’ it is worth quoting at some length:

When Muybridge and Marey made the first scientific research films, they not only invented the technology of cinema but also created its purest aesthetic. For this is the miracle of the science film, its inexhaustible paradox. At the far end extreme of inquisitive, utilitarian research, in the most absolute proscription of aesthetic intentions, cinematic beauty develops as an additional, supernatural gift...The camera alone possesses the secret key to this universe where supreme beauty is identified at once with nature and chance: that is, with all that a certain traditional aesthetic considers the opposite of art. The Surrealists alone foresaw the existence of this art that seeks in the almost impersonal automatism of their imagination a secret factory of images.

Bazin certainly appreciated Painlevé’s films, but his comments here, written in 1947 on the occasion of the International Association of Science Films, a three-day conference at the Musée de l’Homme that Painlevé organized, celebrates Painlevé’s significant contributions after World War II to the popularization of scientific cinema, which occurred primarily through his work as a film programmer. It is worth mentioning in this context his friendship with Georges Franju, who, along with Henri Langlois, was instrumental in founding the Cinématheque française. Painlevé made Franju the secretary general of the Institute of Scientific Cinema in 1945, which Painlevé had founded in 1930 to ensure the distribution of scientific films, and he would go on to write the narration for Georges Franju’s Blood of the Beasts (1949). Painlevé also was a strong public voice for demanding high aesthetic standards from nonfiction films; his essay ‘The Castration of the Documentary,’ a self-described ‘polemic’ originally printed in Cahiers du cinèma in 1953, as an appeal to nonfiction filmmakers to expend the energy necessary to capture ‘the unexpected, the unusual, the lyrical.’ Painlevé’s career continues well beyond the high-water mark of surrealism while also serving as an indication of its persistence (in this sense, resembling Buñuel’s career).

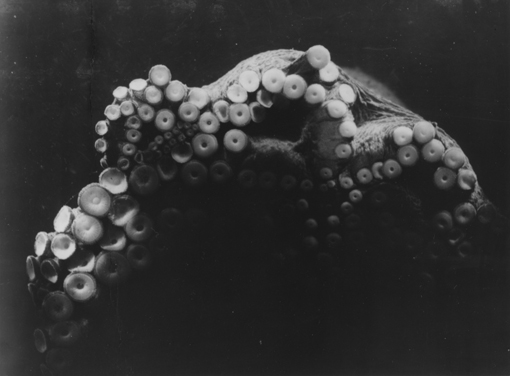

(image: BFI / Courtesy of Brigitte Berg)

Art critic Ralph Rugoff has branded Painlevé’s cinema ‘an adventure in the aesthetics of uncanniness,’ mentioning his tendency to take ‘uncanny hybrids’ as the subjects of his films. The focus of his most popular film, The Seahorse (1934), a bipedal fish that is one of the rare species where the male both carries and then gives birth to live young, is a good example of this tendency. The notion of hybridity is good shorthand for a cohesive thread that runs through Painlevé’s work, because his films defy easy categorization. He frequently is described as a peripheral surrealist, but depending on what films from his nearly 200-title filmography one emphasizes, he also could be described as a science educator, or as a research scientist. The new BFI DVD set (see separate review) will help to bring these compelling films to the wide audience to which they are addressed.

Oliver Gaycken