by Associate Professor Chris Willmott

This article first appeared in ViewFinder 103

There is tangible evidence for the growing importance of moving image in science education. For example, in 2014 an Institute for Scientific Information impact factor was awarded to The Journal of Visualised Experiments and many scientists are now posting educational material on YouTube. In this article I will argue that there is another valuable moving image resource that is often overlooked by academics – broadcast media.

When I have discussed my enthusiasm for using television footage in university bioscience teaching, some colleagues can barely conceal their view that I have suggested forming a pact with the devil. At a recent academic conference one of the delegates said what I'm sure others were thinking - television science is ‘dumbed down’ science.

Now of course to some extent this is absolutely right; a large percentage of science on television is watered down or plain wrong. However a sizeable amount of television science content is accurate and, as I hope to illustrate, even the science that is wrong can be valuable for teaching.

I've come to realise that one of the reasons for scepticism about the merits of using broadcast media in teaching is a belief that the only motivation for doing so would be to convey factual content to students. This is a caricature of Open University broadcasts circa 1975 in which the primary motivation was to replace lectures for students unable to attend full-time, campus-based courses.

Although content can be important I would argue that the primary motivation for showing television clips is to promote engagement. Limitations in the application of broadcast material to science teaching may therefore stem from a lack of creativity, coupled with uncertainty about what might be available, and how to get hold of it. Let's deal with these issues in turn.

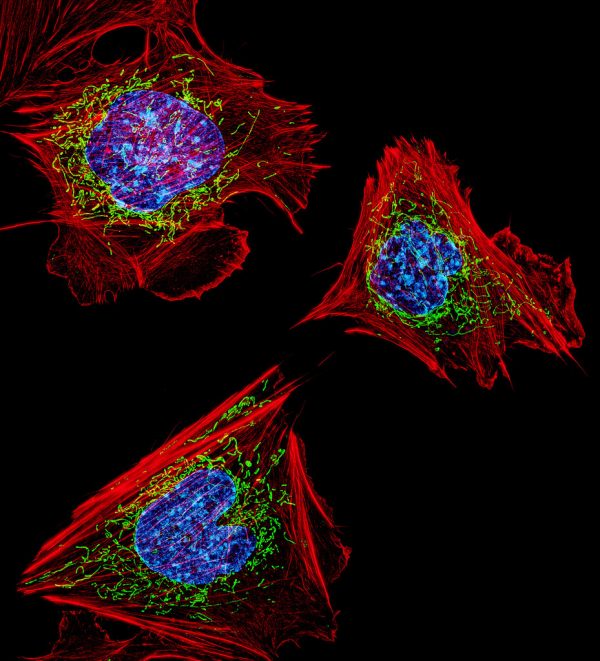

Fibroblast cells with nuclei in blue, mitochondria in green and the actin cytoskeleton in red. (2014 © Flickr / ZEISS Microscopy / CC attribution 2.0)

Creativity

To begin with, consider the importance of creativity. If the suggestion had been made that we should routinely replace our lectures with hours of students sitting passively watching a screen, then I would share any scepticism regarding the value of this approach. However the use of a carefully chosen clip can introduce a new dynamic to a lecture or tutorial. Short extracts can be employed in a variety of ways.

The most obvious use of a clip would be to illustrate some factual point. Rather than describe the processes involved in preimplantation genetic diagnosis, for example, I can include a two-minute clip from Robert Winston’s series A Child Against All Odds (2006), which shows the procedure. Similarly, a short section on the role of cilia in determining the layout of body organs, from Countdown To Life: The Extraordinary Making Of You (2015), presented by Michael Moseley, might help enrich a lecture on the diverse roles of microtubules.

Alternatively, a clip might be used as a scene-setter at the beginning of a session. I have used a couple of short sections from the James Bond film Die Another Day (2002), in which the proprietor of a secretive Cuban clinic explains that gene therapy involves ‘introduction of new DNA from healthy donors; orphans, runaways, people that won’t be missed.’ In this way he is able to transform North Korean Colonel Tan-Sun Moon into British aristocrat Sir Gustav Graves.

Of course this is abject nonsense – gene therapy is something entirely different. But that is exactly the point. This ridiculous storyline serves as a humorous introduction to a lecture when we look in more detail at what gene therapy actual involves and the difficulties that have hampered introduction of far less ambitious changes to the human genome.

Making use of news footage, in this case the rather more tragic case of Eloise Parry, can be used to bring human interest to a lecture on mitochondrial uncoupling. This young woman bought ‘DNP’ (2,4-dinitrophenol) online as an aid to slimming and took several pills in quick succession, triggering a fatal metabolic response. Alternatively a lecture on muscle biochemistry might benefit from inclusion of news reports about an improved technique for determining the concentration of troponin in the blood of a patient with a suspected heart attack.

Thirdly, a clip might be used as a discussion starter. For several years I have run a workshop on experimental design for first year undergraduates, in which I have used a section from the populist science series Brainiac: Science Abuse. In the clip, presenter Richard Hammond supervises an experiment that he concludes ‘proves’ humans can smell fear. Of course the method shown does nothing of the sort, even if we put to one side philosophical debates about the notion of proof.

Once again, however, the poor quality of the science is exactly the point. Students are asked to watch the clip and keep an eye out for aspects of the experiment that are good, and those features that are less good. These observations are then collated, before the students are set the task of working with their neighbours to design a better study posing the same question.

There will be occasions when the content of a programme is sufficiently strong to warrant watching it in its entirety. Examples that are worthy of this attention include The Battle to Beat Polio (2014), any episode of the series Pain, Pus and Poison (2015) and The Chemistry of Life, which is the second episode of Adam Rutherford’s trilogy The Cell (2011). The Chemistry of Life is a sixty-minute documentary that provides a beautiful walk through of the experiments that identified DNA as the molecule of inheritance, and I have, in the past, committed a full session to watching this programme with first year students – providing them with a structured sheet to aid their note-taking.

As discussed this may not always be the most appropriate use of valuable face-to-face time and there are practical difficulties in watching a full one hour documentary in a fifty-minute lecture slot. A few years ago, there was no genuine alternative; if your class contained more than a handful of students and you felt it was worthwhile them all seeing something then you had to commit the necessary time. This is no longer the case. The rise of authorised archives of streamed television (such as Box of Broadcasts, Planet e-Stream and ClickView) and on-demand television services make it possible to set students the task of watching a particular programme at home. In this way, watching broadcast media becomes a component of a flipped learning teaching model.

Awareness

The second limitation we identified previously was a lack of awareness of what broadcast material might be available. It is quite possible that a section of a programme would be pertinent to a basic concept about which you are teaching, but how are you to use it if you don’t know it exists?

In the UK we are blessed with a number of valuable tools to help in tracking down relevant broadcasts. In addition to the websites of broadcasters themselves, and search facilities within the archives, there is also the Television and Radio Index for Learning and Teaching (www.trilt.ac.uk). TRILT includes a significant amount of metadata relating to programmes but ever this will not necessarily provide nuanced guidance for ways in which they could be used within the context of science teaching.

This is where new service Biology on the Box (www.biologyonthebox.wordpress.com) comes in. Posts in a variety of styles highlight television (and to a lesser extent radio) material of relevance to undergraduate bioscience, with recommendations coming from both academics and students. Some items merely raises awareness of the existence of digital copies of programmes, others include reviews, structured activities and/or tried-and-tested classroom applications. Other disciplines are also developing subject-specific resources (e.g. www.historyonthebox.wordpress.com). If you would like to consider developing the use of broadcast media in your own teaching, you could do worse than look around one of these sites to get a feel for the different ways in which television and radio might be exploited more fully.

About the Author:

Chris Willmott is Assistant Professor in Biochemistry at the University of Leicester and has a special interest in bioethics teaching. He is the author of the BioethicsBytes blog: bioethicsbytes.wordpress.com, which recommends clips for teaching about bioethics. He has also contributed chapters to two books on Doctor Who and philosophy.

(An earlier version of this article appeared in the December 2015 edition of The Biochemist, the magazine of the Biochemical Society.)