by Dr Margaretta Jolly and Dr Polly Russell

This article first appeared in ViewFinder 98

The Women’s Liberation Movement Oral History Project – Sisterhood and After (SAA) – grew out of the determination that the voices of those who lived through the extraordinary feminisms the 1970s and 80s be remembered. Margaretta Jolly, in partnership with Polly Russell, a curator-researcher at the British Library, and supported by scholar-activist advisors, happily completed the project in 2014, having been funded by the Leverhulme Trust over three years to capture and interpret sixty life history interviews with core activists across the UK.[1]

Our primary aim has been to create a permanent multimedia archive in a beautiful and powerful library where subsequent generations can discover the work of the movement pioneers of the 1960s-80s. The oral history method but also digital audio/visual resources have been vital in making this happen. In this article we show how the already visceral effect of intimate interviews was enhanced by the design of a website and supporting films, particularly valuable for capturing young and activist audiences as well as the more usual academic ones. We also argue that web technology can help mitigate the distance between academic and non-academic audiences as well as allowing more fluidity in the interpretation of archival material. Finally, we consider the role of a sound installation in the project.

The website, films and sound installation of course would not exist without the full oral histories. Archived, along with full transcripts, these recordings and transcripts are available for listening on-site at the British Library in London to library readers, subject to interviewee permission.[2] In attempting to understand the impetus and trajectory of an interviewee’s activism, the recordings cover family background, childhood, education, work experience and relationships. These recordings therefore document an individual’s engagement with the WLM while taking account of the context in which this activism was situated. The average length of these recordings is 7 hours but many are significantly longer. For those interested in the history and sociology of social movements, in women’s history, in twentieth century history, gender studies or narrative identity, the SAA oral archive is a rich resource.

Rebecca Johnson being arrested (image used with permission from Rebecca Johnson).

However, the very richness that makes the collection so valuable to researchers, can, for less specialist audiences, be an impediment. Not everyone is able to visit the British Library to access material and, even if they were, the volume of material available in any one of these recordings, even with transcripts and summaries as guides, requires significant navigation. For this reason, written into the funding application for the SAA project was provision to create a website and ten short films to be hosted on the British Library’s Learning platform.[3] Working closely with colleagues in the Learning Team, the website was designed for secondary school and undergraduate students, feminist activists and lifelong learners. Though the basic template for the website, involving a homepage and thematic sub-pages, was determined by the library’s pre-existing website infrastructure, decisions about what to present of the complex and contested history of the WLM involved much discussion. Just as choosing 60 people to interview from the thousands of women who were central to the movement was a challenge, creating the website took almost a year’s collective work.

Ultimately we were guided by the content of the recordings and the website took shape under ten headings with each of these sub-divided into two or three more. A section on ‘Politics and Legislation’ contains sub-sections on ‘The Political Representation of Women’, ‘Feminist Critique of Political Culture’ and ‘The Impact of Legislation on Women’s Lives’ for example. Or a section focused on ‘Education’ has sub-sections covering ‘How Girls were Taught and Socialised’, ‘Sex Education’ and ‘Women’s Studies and Women’s History.’

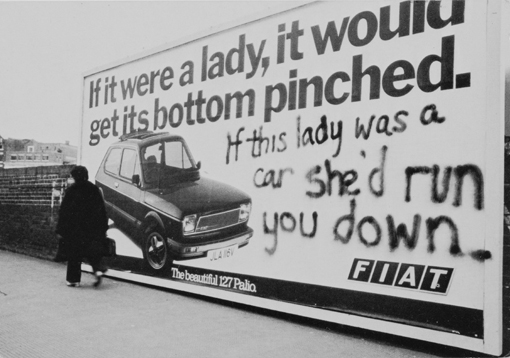

‘If this lady was a car’ photograph © Jill Posener (courtesy of the British Library)

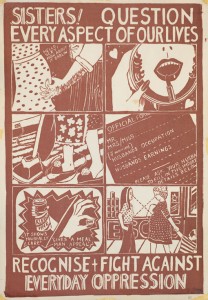

Each of these thematic areas is populated with contextual information, images, cartoons and photographs as well as questions to instigate discussion, but what brings the website to life are its 125 sound extracts, selected from the oral history recordings, and the ten bespoke films which we commissioned from feminist filmmaker Lizzie Thynne. [4] These sound extracts and films represent the diversity of experience and views of the WLM activists. Site visitors can hear, for instance, Pragna Patel, co-founder of Southall Black Sisters, describe a ‘reverse march of shame’ to the house of a domestic abuser. They can listen to Una Kroll, 86 year old campaigner for women’s right to be priests, describe her struggles with the church. Or they can discover Rebecca Johnson, life time peace activist, recounting the strategies of Greenham Common women. Johnson’s story was one that Thynne selected for filming, for its obvious visual as well as oral drama.

Return to Sender follows Johnson to the monthly women’s peace camp at Aldermaston where nuclear weapons are still being made, and to the now tranquil common where feminists had previously helped to secure the successful return of cruise missiles to the US twenty years ago. This film also draws on the plentiful footage available of the Greenham protest – something that we discovered to be painfully absent for much of the rest of the Women’s Liberation movement. One of our most interesting discussions was about Thynne’s much more intimate filming of National Abortion Campaign coordinator Jan McKenley at home. The feelings behind the slogans shows McKenley reflecting on her personal experience of abortion and the importance of being able to grieve while upholding a woman’s right to choose. McKenley remembers too the importance of a women’s health group in allowing her to cherish her own body. We decided to present the film in four linked parts across the website’s sections on ‘Activism’ and on ‘Bodies, Minds and Spirits’, framed with questions that ask viewers not only to think about the complications of liberation and reproductive rights, but whether they themselves might be able to ‘imagine feeling differently, as you grow older, about some of the life choices you took (if you were lucky enough to have choices)?’

(image credit: See Red)

The design of these audio/visual routes into the history are part of our hope that the project as a whole will challenge stereotypes and make the ongoing relevance of the WLM evident to today’s generations. Of course they do beg questions as to the subtle relationship of oral to visual to textual versions of the past. It was a great pleasure, then, to work with Thynne in producing ‘Voices in Movement’, a soundwork which allowed for a more open and non-realist approach. In its first form, this was a multi-channel sound installation at ‘Public and Private Archives: Creative Negotiations’, Sussex University, April 2014. It was then shown as a single screen work as part of the group show, ‘Family Ties; Reframing Memory’ Peltz Gallery, London 3 – 25 July 2014. This fifteen-minute soundwork has pushed the ‘post-documentary’ potential of our recordings to complicate any direct correspondence between voice, person and location. Instead, Thynne denaturalises and plays with the vocal and the testimonial, drawing out the formal and relational elements of the interview as constructive space. Thynne uses visuals sparingly – such as fleeting archive of period home movies and only briefly glimpsed photographs of the speakers, and thus provides a meditative texture quite different to the necessarily more didactic films and website.

Response to the SAA project has been encouraging both in terms of website visit statistics and also the various conversations, research and events it has inspired. In the first 4 months of the website launching it received 50,000 visits and since it has been available daily visit numbers for unique users have consistently been around 350. Heartening too have been the requests from schools visiting the British Library for SAA workshops – more than 500 school children have attended. Through these workshops students have been introduced to archive recordings, have discussed gender and women’s liberation and have reflected on why the recordings were collected. Vivid and expressive, oral history extracts have a powerful capacity to engage students. Even the most reticent class has been galvanized into discussion by hearing Deirdre Beddoe, Professor of History at the University of Glamorgan, describe how, at primary school, she was told she had to be a sailor’s wife not a sailor.

Beyond the library, the website and archive have been the catalysts for a number of different events, including by the East London Fawcett Society, with an audience of 200 young activists and a sellout conference ‘In Conversation with the WLM’ at The British Library. Both these events and others involved delegates and speakers debating archive material in relation to contemporary concerns and suggest that web technology, in combination with oral and audiovisual material can help enable the archive come to life. That SAA is contributing to larger conversation is important as the project team have been actively inspired by the democratic ideals of oral historical method and of feminism itself. We were acutely aware of other feminist archives and libraries, websites, blogs and histories – which we list on the ‘About Us’ tab of the website – and indeed we make no claims to be the definitive account of the Movement or the sole repository of that history. The fact that ‘Sisterhood and After’ is one resource among many is precisely our hope, for feminist history, feminism and gender relations remain as pertinent, complex and in need of multimediation as ever.

[1] In line with library policy, the British Library & University of Sussex required all interviewees to sign an interview release form stipulating how their recordings could be accessed. Interviewees were able to ‘close’ sections or the entirety of their recordings for a named number of years if desired.

[2] For more information, see http://www.sussex.ac.uk/clhlwr/research/sisterhoodafter and http://www.sussex.ac.uk/research/impact/cultureandsociety/bwlm

[3] The website can be accessed at bl.uk/sisterhood

[4] http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/conversations/archive2013/thynne/

About the Authors:

Dr Margaretta Jolly is a cultural critic with a particular interest in life writing and life history. Her work has focused on auto/biography and oral history, feminist theory and social movement history. She is Reader in Cultural Studies, University of Sussex. Her publications include In Love and Struggle: Letters in Contemporary Feminism (2008, Columbia University Press).

Dr Polly Russell, Lead Curator, The British Library where she is responsible for developing collections and services in the fields of Politics and Public Life, Food Studies and Women’s History. She is also a freelance food consultant and writer and works with Heston Blumenthal as his historical researcher.

Sisterhood and After was funded by the Leverhulme Trust. It was led by Margaretta Jolly from the Centre for Life History and Life Writing Research at Sussex University in partnership with The British Library and The Women’s Library.