by Dipali Das, Edge Hill University

In the early 1980s, the price of a cinema ticket in Britain was approaching £2, compared to the cost of an annual black and white television licence at £15. Films such as The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Superman II (1980) and E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (1982), came and went unseen, particularly for families from low-income households. My parents explained it was unnecessary to pay so much money, as these films would eventually be shown on television for free. I just had to wait a few years. Network premieres became a celebrated event, especially during the Christmas holidays, when we enjoyed innumerable blockbusters on the small screen. Accessing Indian cinema was a slightly more complex matter.

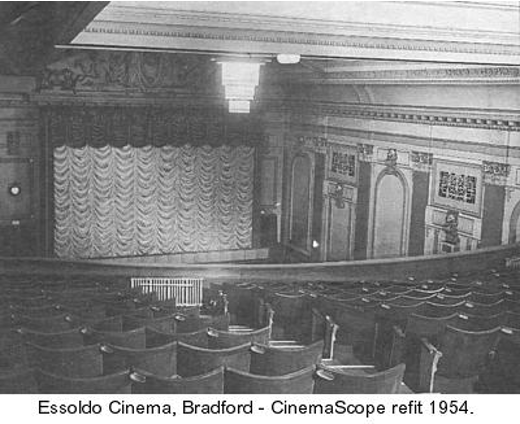

During the 1960s, as British Asian populations increased in urban areas including Bradford, Leicester and Southall, cinema venues such as the Essoldo, gradually recognised there was an audience for Indian films and catered for them by screening popular releases of the time at the weekends. However, smaller towns, even with a sizeable British Asian population, did not have enough of an audience to convince the local cinemas to show Indian films. Once again, accessing films at a cinema was not a straightforward task.

In keeping with the DIY ethic of the late 1970s and 80s, to provide an essential community service for British Asians, pirate copies of Indian films began circulating across the country, available to hire on VHS (Video Home System) cassettes. During this period, my father would disappear for a short while on a Saturday morning and return with a colour television, a video cassette recorder, some cables and three or four cassettes, all costing around £5. A film marathon would ensue for ten hours or so and then all the equipment and tapes would be returned the following day. Later, I would wonder about the people who did not have a local pirate video provider in their area and no Indian films showing at their local cinema. This became the starting point for my PhD, with the aim to explore the accessibility and availability of Indian cinema on British television prior to the advent of digital and satellite channels and streaming platforms.

My film worlds existed in parallel spheres. European and US films were broadcast on the three analogue channels, BBC1, BBC2 and ITV, whilst the pirate videos of Indian films provided me with an alternative education of World cinema. The experience of accessing film through television was my normal, where cinema was historically and culturally intertwined with television, existing as long-standing companions. Yet, researching their respective academic histories recently, it is apparent tensions exist between Film studies and Television studies. Also, there is an unwillingness to examine, in any depth, relationships between the two disciplines (Andrews, 2014). Literature addressing the relationship between Indian cinema and British terrestrial television is noticeable by its absence.

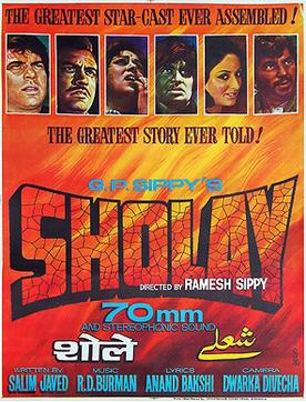

On the 26th of December 1982, my very separate worlds of Indian cinema and broadcast television collided. Almost eight weeks after launching, Channel 4 screened the network premiere of Sholay (Ramesh Sippy, 1975). Although we had watched it a couple of years earlier, we soon realised the quality of the print broadcast by Channel 4 was far superior to the grainy images we had been previously subjected to. The scratchy tape that had creaked along, with grey snowy lines travelling horizontally across the screen every so often, due to being copied to within an inch of its life, was now a distant memory. However, it was the inclusion of English subtitles that redefined the whole viewing experience.

Film poster of Sholay (1975)

The pirate videos we hired rarely had English subtitles. The dialogue in Indian films, usually from Mumbai, was Hindustani, a mixture of Hindi and Urdu, which my parents understood but I did not. As a consequence, I would keep asking what was happening, only to be ignored as my parents understandably did not want to miss anything. The songs provided an interlude where I was brought up to speed with events from the past half hour. The subtitles which accompanied Sholay enabled English speaking audiences to understand a modern classic of Indian cinema. In addition, British Asians, who were non-Hindustani speakers, now had the opportunity to better appreciate and enjoy a film, which previously they could not, due to the language barrier. As noted in the Channel 4 Press Pack for that week, Sholay was ‘the forerunner of a series devoted to popular Indian cinema, All India Talkies’, curated by Nasreen Munni Kabir, which runs to this day, now known as Channel 4’s Indian Film Season.

It should be noted Sholay was not the first Indian film to be broadcast on British television. Amar Akbar Anthony (1977) was screened on BBC1 in 1980, yet it was treated with some disdain. Firstly, it was excluded from the film listings in the Radio Times and secondly, at just over 3 hours long, the BBC decided to cut the first two reels and most of the songs (Thomas, 1985). These actions caused the plotlines and the narrative to become disjointed, causing confusion for viewers, including those who had already seen the film. Appadurai recognised when ‘moving images meet deterritorialized viewers’ (1996: 4), diasporas could be presented with films by institutions, who are unfamiliar with the culture and context, and this can be disconcerting. The importance of watching a film without external editing or censorship cannot be overstated. It is worth noting Gone With The Wind (1939) and Once Upon a Time In America (1984) both have significantly longer running times than Amar Akbar Anthony, and were broadcast on the BBC without any cuts or edits. By screening Sholay in its entirety, Channel 4 demonstrated a respect, both for Indian cinema and their viewers.

Nasreen Munni Kabir in conversation with legendary playback singer, Lata Mangeshkar

In September 1987, with little fanfare or publicity, a programme appeared on Channel 4 about Indian cinema. Movie Mahal (1987-1989), directed by Nasreen Munni Kabir and was pioneering in so many ways. Only two series were ever produced, and they created an appreciation and understanding of Indian cinema barely seen previously or since on British television. During the initial stages of research, I discovered a solitary article from 1988 by Paul Oliver. Writing from a musician’s perspective, he encouraged the reader to make a concerted effort to wake up early on Sunday morning and tune in. Once again, the inclusion of subtitles was indispensable for my younger self, in being able to understand the dialogue during the film clips and when practitioners shared their memories. Also, with no voices dubbed into English, when the cast and crew shared their insights and experiences in Hindi, it enabled our family to access and enjoy the programme based on our own bilingual abilities.

In 1965, the BBC set up the Immigrants Programme Unit (IPU). The programmes produced for the South Asian diaspora were always scheduled for broadcast early Sunday morning and this continued for the next two decades. Consciously or unconsciously, Channel 4 maintained this traditional time slot for Asian programming and Movie Mahal was also broadcast on a Sunday morning at 9.25am. As we ate our omelettes spiked with chillies and onions, alongside a precarious tower of hot buttery toast, and mugs of masala chai, we enjoyed songs from classic films, such as Andaz (1949), Pyaasa (1957) and Gunga Jumna (1961). In addition, historical and informative notes about each film would pop up at random moments and scroll along the screen in tickertape mode.

Film poster of Pyaasa (1957)

Over the decades British television produced sitcoms, such as It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum, (BBC, 1973-1981) and Mind Your Language (ITV, 1977-1979, 1985), where South Asian characters were subjected to varying degrees of humiliation on a weekly basis, and we would watch anyway. Despite the awful stereotypes, seeing ourselves on television was slightly preferable to not seeing any brown people at all. In stark contrast, the largely positive representation of South Asians on Channel 4, through the Indian Film Seasons and the ground-breaking Movie Mahal, provided alternative perspectives and perhaps assisted in developing a sense of self.

A generation of British Asians were (re) introduced to the golden era of Indian cinema and discovered a film history and cultural heritage they may have been unaware of. When we saw ourselves, we had agency, courage, glamour and some spectacular dance moves and this time it was not confined to the private sphere of pirate videos. We had to wait a few years, but eventually Channel 4 brought Indian Cinema to the small screen, and we celebrated.

About the Author

Dipali Das is a second year PhD student in Media Studies at Edge Hill University. Her thesis is entitled ‘Sunday Mornings with Nai Zindagi Naya Jeevan and Movie Mahal: Accessing Indian Cinema on British Terrestrial Television from 1968-1989’. In 2020, after pursuing careers in Engineering and Teaching, she completed an MA in Film and Media, which examined the role and representation of the sari during colonial and post-colonial Indian Cinema.

Bibliography

Andrews, H. (2014) Television and British Cinema: Convergence and Divergence Since 1990. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appadurai, A. (1996) Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Oliver, P. (1988) ‘Middle Eight - Movie Mahal: Indian cinema on ITV Channel 4’ Popular Music. 7 (2) pp. 215-216

Thomas, R. (1985) ‘Indian Cinema: Pleasures and Popularity’ Screen. 26 (3) pp. 116-131

Channel 4 Press Packs, "Movie highlights: 1982 week 52 page 35” http://bufvc.ac.uk/tvandradio/c4pp/search/index.php/page/c4_pp_1982_52_1225_1231_035_movhigh (Accessed 08 Nov 2022)