by Jack Booth

Lars von Trier builds his films around leitmotifs that provide an eerie stability for the viewer. In The House That Jack Built this is no different, von Trier works in ‘Fame’ by David Bowie at moments of extreme cruelty. The sultry energy of the song gives the morbidity of the scenes it is played over a harrowing jouissance. The lyrics, particularly the opening three lines, aptly encapsulate the tone of the film:

Fame (fame) makes a man take things over

Fame (fame) lets him lose hard to swallow

Fame (fame) puts you there where things are hollow

The second fame, the ‘(fame)’, is sung in falsetto by John Lennon, who originally provided the catalyst for the word ‘fame’ by singing ‘aim’ almost as a chant in a session he did with Bowie in New York in 1975. The song provides a pertinent reminder of the sometimes macabre, complexities of fame, not least because Lennon was shot dead by a fan five years later. In von Trier’s film the song takes on a warped materiality in the form of mangled female corpses, the line ‘makes a man take things over’ literally becoming a man who takes the life of someone else.

Bowie’s alignment with the themes of death and extreme violence, is a quality that Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi also recognises in the late artist’s song ‘Heroes’. Berardi titled his book Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide after Bowie’s song and saw the year the song was released, 1977, as the year in which there are no longer anymore heroes. For Berardi the song articulated the death of the hero and the beginning of an epoch where heroes have turned spectral and monstrous, made through the ‘endless flowing recombination of fragmentary images.’ The figure of the hero, for Berardi, has become both victim and victimiser of the logics of neoliberal precarity that drives masculine competition to the point of individual mental and physical annihilation. The line ‘we can be Heroes, just for one day’ is given a moribund tone as Berardi relates the song to the competitive masculine impulse to become someone notable no matter the cost.

Berardi and von Trier both deal with a particular type of negative and extreme masculinity, behaviours of which can be aligned with the term toxic masculinity. What underlies their depictions of this subject is how these behaviours are created both by the individual and through the social structures that surround the individual. These two factors converge in the drive towards success at any cost and the desire to achieve symbolic forms of celebrity. I will examinine how The House That Jack Built depicts toxic masculinity and its relation to how a striving for success can become subverted and socially regressive.

Toxic Masculinity is defined by Terry Kupers as a set of traits clearly observable in prisoners within the United States penal system. Kupers states that:

‘Toxic masculinity is the constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia, and wanton violence. Toxic masculinity also includes a strong measure of the male proclivities that lead to resistance in psychotherapy.’ (Kupers, Toxic Masculinity as a Barrier to Mental Health Treatment in Prison 2005)

Kupers shows that toxic masculinity is built up through various factors and is a behaviour that is not solely isolated to an individual. Kupers states that toxic masculinity can be seen as occurring in a multitude of ways:

- Through a mentally ill individual.

Lack of mental health care provision in prison.

Overcrowding and lack of meaningful activity for prisons.

Legal impediments to healthcare, meaning that when patients do receive health care, confidentiality agreements restrict how patients interact with the clinician, to the point where the patient is unwilling to even receive treatment for fear of worsening his situation.

Prison guards intensify, and to some extent replicate, toxic masculine behaviours. Kupers gives an example of the ‘process of cell extraction’ where prison guards will replicate the aggression shown by the prisoner.

While not going as far to suggest this type of masculinity acts as a contagion, Kupers states that ‘toxic masculinity that is fostered in prison is spread beyond prison walls’ upon release of certain prisoners. Suggesting the prisoners in effect take the prison environment out with them. What these, Kupers terms, ‘contextual variables’ show is that toxic masculinity is created in relation, rather allowing the individual to be given as the sole genesis of this set of behaviours.

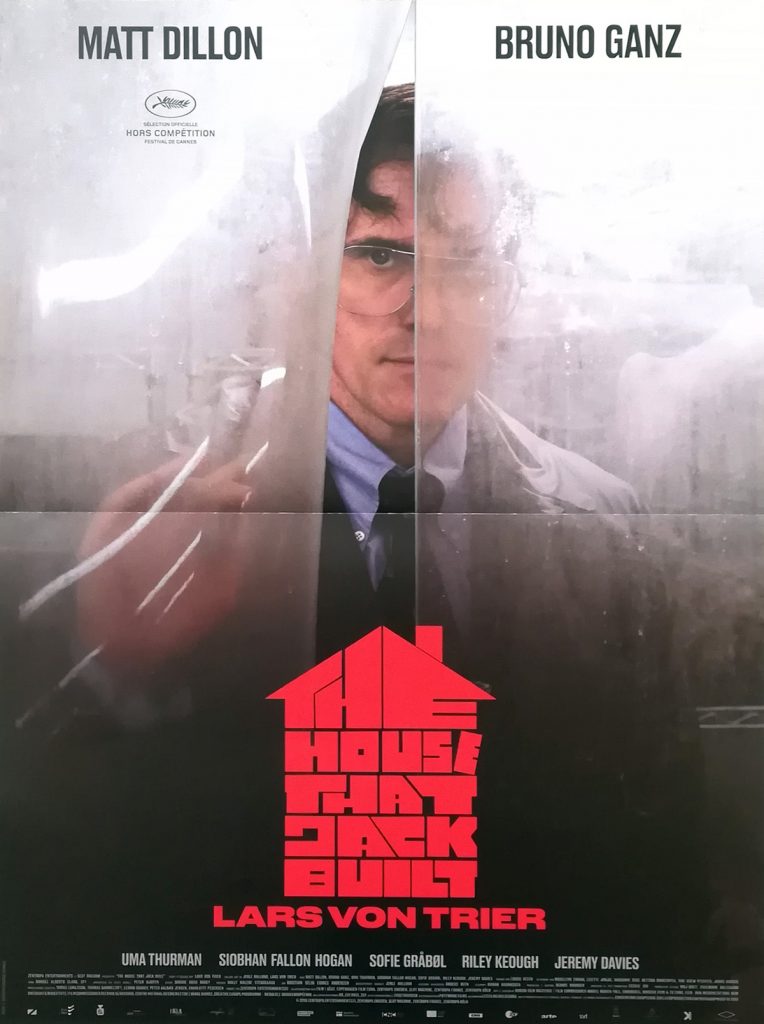

The House That Jack Built Film Poster

The third reason that Jack murders in the film is to fulfil the ideal of success. A prominent behaviour of toxic masculinity is the desire to win, to be successful, and to dominate. There are two prominent strands in the film that illustrate this will to win. The first strand is the idea of celebrity and how this can easily become subverted into seeking notoriety. Von Trier comments on this through Jack’s ‘hobby’ of taking photographs of his victims, which then sends into the local paper under the moniker of ‘Mr. Sophistication’. The second strand comments on the more quotidian ambition of succeeding in a white-collar profession. The film states that because of a large inheritance that Jack has received he is permitted to pursue his dream of becoming an architect. He was trained as an engineer but now he has the time and resources to fulfil his desire of being an architect. He buys his own plot of land and intends to build a house on it. Throughout the film Jack makes various attempts to design and build a house all that end up failing. The only house that Jack ever ends up building is a house made up of dead women. This narrative arc shows the pernicious side of how having, even a relatively, minor ambition can become sinister when it is unfulfilled. The desire to succeed and dominate is shown to toxify through the individual but also through the social expectation to succeed that is shown to be active even in quotidian ideal of self-betterment; here shown through attaining a higher status job. Von Trier alludes to how toxic masculinity arises mainly through three ways.

- The individual with serious mental illness.

-

Social history and societal abnegation that has tried to render men infallible and inculpable. Also, the individual who is poorly provided for in terms of mental health care.

-

The cult of success. Von Trier particularly and predictably critiques the bourgeois formulation of this desire through the examination of the desire to ascend within the hierarchy of a white-collar professions. He also demonstrates perversion of the will to attain celebrity status.

<

p>Through the use of the song ‘Fame’ von Trier manages to distil an essence of what allows these behaviours to become active. Towards the end of the song Bowie sings:

To bind our time it drives you to crime (crime)

Fame (fame)

The song creates a bind within the viewer who simultaneously enjoys a popular song while seeing images of extreme violence. It sets up a schism in the viewer between individual and social responsibility. The viewer’s enjoyment of the song and the horrifying violence of the scenes it is played over, make the two states inseparable and in doing so implicate the viewer, rather than ameliorating their sense of responsibility or guilt.

There is no sense negating the individual’s responsibility in the face of atrocities they commit. However, Kupers outlines toxic masculinity is not ‘formed in a vacuum’ and therefore is the relation of individual to external factors. Through the depiction of serial killers as occurring within a vacuum the relationality of their crimes recedes from view. As a result, we are left with a sensationalist judgement of a type of masculinity that obscures a wider sense of responsibility. Berardi’s lament of the hero turned spectre is the lament of the collapse of common responsibility, and the disappearance of the ‘shared conditions of ethical behaviour’. The House That Jack Built points to this disappearance, showing how wanton violence is facilitated through the abnegation of social responsibility, allowing toxic masculine behaviours of domination and ruthless competition to occur in its wake.

About the Author:

Jack Booth is an independent writer and researcher, based in London. His interests include media history and contemporary cinema. He has recently completed a Masters from University College London in Film Studies and holds an BA in History from Goldsmiths, University of London.