The Royal College of Music and The Open University have created the Listening Experience Database (LED), an ambitious three-year project, funded by the AHRC, to document the impact of music on people’s lives. Simon Brown, Research Associate, The Listening Experience Database, puts his ear to the ground.

About the author: Simon Brown graduated with a BA (Hons) in music from The University of Nottingham. In May 2008 he won the Bernard Slee Music Award for his paper on Wagner’s opera, Das Rheingold. He then subsequently received an award from The Society for Music Analysis, together with a scholarship by The University of Nottingham that enabled him to gain an MA in Music in 2009. Later that same year, he won a Collaborative Doctoral Award funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council to study for a PhD at Birmingham Conservatoire. He is also an Associate Lecturer with The Open University and is the Research Associate at the RCM working on The Listening Experience Database project.

Overview of the project In his speech, ‘On Receiving the First Aspen Award’, Benjamin Britten described ‘true musical experience’ as a ‘holy triangle of composer, performer and listener’. When we think of this concept, we usually consider it to be three equal sides of a triangle, with all three participants in the musical experience being equal partners. However, when we consider the written history of music, things are anything but equal; you only need to visit the library or retrieve a quick Internet search to reveal the vast amounts of information on composers and performers. These are the people we celebrate, whose names enter the imaginary museum of musical works. For most people, they are the focus of our attention, but what about the listeners? If we accept Britten’s idea that the listener is an intrinsic and vital part of the experience – how can we hope to understand the history of music if we’re only getting two thirds of the story?

… how can we hope to understand the history of music if we’re only getting two thirds of the story?

The Royal College of Music has joined forces with The Open University to create the Listening Experience Database (LED). This ambitious three-year project, funded by a £750,000 research grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, aims to produce the world’s first database documenting the impact of music on people’s lives. The main purpose of the project is to design and develop a database, freely searchable by the public, which will bring together a mass of data about people’s experiences of listening to music of all kinds, in any historical period and any culture. It is also using crowdsourcing as one of the ways to populate the database.

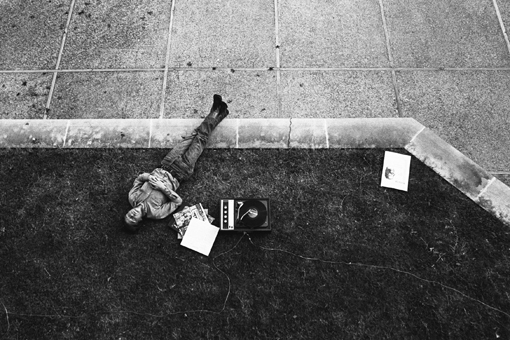

Street musicians, May 1989, New Orleans, photographed by Brenda Anderson. (Photo © Brenda Anderson)

Aims & technical issues involved in delivering the content online The project team includes staff of the OU’s Knowledge Media Institute (KMi), which pursues cutting-edge research into areas such as semantic technologies and multimedia. They have designed the online entry form to be as intuitive as possible. We were conscious that the form needed to cater for an array of different listening experiences supplied by contributors with varying amounts of information. Each listening experience is unique, not only in the precise detail of the evidence being supplied, but also in terms of the peripheral information that is just as important: for instance, the type of source the experience appears in (such as a letter or diary entry, which might appear in a published book or equally in an unpublished manuscript); when the experience occurred (at a specific time on a single day or over several days, weeks or even years); what the piece of music was, who performed it, where it was performed, and if this differed from where and how it was heard. The evidence might describe an experience of an individual or of a crowd. The listener might not even be mentioned by name, but given a description such as ‘A Shopkeeper’ or ‘A group of soldiers’. Contributors will not necessarily have all of this information to hand. Yet it was important to ensure that the interface was both intuitive and versatile enough to accommodate as much information as they might be able or willing to offer.

... one of the principal ways in which this technical challenge has been met, was through the use of Linked Data

One of the principal ways in which this technical challenge has been met, was through the use of Linked Data. This is about using the Web to connect related data that wasn’t previously associated. So for example, rather than having to type in all of the details of a particular piece of music or listener, the database will use external sources to search against what the contributor has typed. If they are found elsewhere on the Web, the entry form will return these suggestions, saving the user time and effort and forging a relationship between LED data and the external source. If a contributor suggests that the listening experience involved a piece by Dizzee Rascal, the details of this music will be known elsewhere, as will his biographical details, and these can be retrieved using Linked Data.

What is equally impressive - and to our knowledge LED is one of the first projects that uses crowdsourcing to attempt such a thing - is that when ‘new’ data is created within LED’s own platform, this is then accessible via other Linked Data sites. It’s a little like creating a new record on Wikipedia that other sites such as Google can then link to, but more than that, it is a means to building more useful relationships between different bits of data on the Web – try searching on Google for ‘Dizzee Rascal’ or any other known individual and you will see an assortment of information returned on the right hand side, none of which you particularly asked for but which is potentially useful and relevant nonetheless.

Having just completed the first year of the project, the entry form has undergone its initial phase of development and the database is up and running. The LED project team is now inviting you to participate.

Yes Music in the Amphitheater, students listening to music, 1970. (Photo © Ed Uthman)

What kind of evidence are we after? Music is heard in many contexts by many different kinds of people with different levels of attention and musical knowledge – at one end of the spectrum might be, say, radio listeners, concert-goers or amateur musicians, and at the other, people who encounter music in a more incidental way – perhaps travellers or passers-by in the street or the park. We want to document reactions and opinions across this spectrum, and from whatever period and cultural context they come.

... music is heard in many contexts by many different kinds of people with different levels of attention and musical knowledge

We are looking for essentially private and personal experiences of listening to music that are documented, rather than professional music criticism or reviews of performances or recordings. By ‘documented’ evidence, we really mean things like diaries, memoirs, letters and oral history – things that are already written down or recorded. The parameters of the project don’t allow us to ‘solicit’ responses specially created for LED, so – for example – we’re not looking for your own reflections about a piece of music you heard on the radio the other night or what you’re listening to on your iPod, or a childhood memory of listening to music. What we are really keen to uncover is the hidden cache of family letters or diaries held in your loft, or the journals of a traveller held in your local library, archive or society. Provided that they have already been written or documented, LED isn’t concerned with the quality of the writing. It’s not about collecting highly literate accounts by prominent people. It’s about collating honest accounts of musical experiences from any era, culture or type of listener.

For the time being, so that the initial three-year phase of the project is focused and manageable, entries will be restricted to English-language sources, but our intention is that, in the future, the project will expand to take in a network of international participants, and that the database will ultimately include sources in other languages.

The database will help us to form a better understanding of the effect of music on listeners and the ways in which it is, and has been, valued and understood in society. Amongst other things, it will enhance our understanding of how recording and broadcasting technologies have affected people’s relationship with music, and offer a new range of evidence of how music is studied and learned. It will also sharpen our insight into the settings and ways in which music has been performed – how, for example, it has been used in the home and in religious rituals.

It is hoped that the data will interest a wide range of people – performers, teachers, social historians, music historians, psychologists of music, people working in the creative industries – indeed, anyone with an interest in the performance and reception of music. To find out more and learn how you can get involved, visit: www.open.ac.uk/Arts/LED

It is hoped that the data will interest a wide range of people – performers, teachers, social historians, music historians, psychologists of music, people working in the creative industries – indeed, anyone with an interest in the performance and reception of music. To find out more and learn how you can get involved, visit: www.open.ac.uk/Arts/LED

Simon Brown