by Mariana Pintado-Zurita, University of Glasgow

Anyone familiar with the film Blade Runner (1982) will know that memory takes a vital role in its narrative. This remains the case for its sequel, Blade Runner 2049 (2017), albeit from a somewhat altered perspective. At the heart of both Blade Runner films is the boundary between "artificial" and "real" memories, and the implications of this ambiguity on an individual’s sense of identity. In a nutshell, one could say a memory is real when that which is remembered really occurred in the past and is a part of history. An artificial memory, on the other hand, only exists in the mind of who "remembers." This distinction is central to the issue between memory and history, where memory is regarded as the "bad twin brother to history" (Neimeyer, 2014: 4). For Katharina Neimeyer memory and history are by no accounts the same; however, it has become increasingly difficult to define the frontiers of each category. Moreover, memory is one of history's objects itself (ibid: 3-4). As she explains, the two have always been intertwined and at many points figure as unrecognisable from each other. It has always been challenging to determine what memories are "real", and therefore suitable to incorporate in historiography. It is important to distinguish memory from history, but memory "is essential for 'historical elaboration'" (ibid: 4). However, this "ability to remember the past, and to actualise it, includes the imperfections of the human mind and endorses sometimes voluntarily embellished or falsified memories on an individual and collective level" (ibid: 3 my emphasis). For this reason, media has been developed to aid the fallibility of human memory. Many media have been created as tools to help preserve memory throughout time: from the invention of the first tax records to the many kinds of recording apps now readily available in our pockets, be it for photographs, video, or audio recording. As technology develops these media become increasingly sophisticated, with larger capacity and easier accessibility. Think of the ‘cloud’ and its increasing features to access as many digital files as possible anywhere you might be. Media such as this allows users to "activate, frame and render memory shareable" (ibid: 4) beyond the temporal and spatial confines of a single person's mind.

One the face of it, it might be counterintuitive to think of a science fiction film, like Blade Runner, as concerned with the past. However, the memory of the past is a crucial resource to imagine and articulate future possibilities, which is why there is a close relationship between history and science fiction. According to Janice Liedl (2015), science fiction can also be a historical genre. It follows historical patterns in its interpretation of the future. A projection of the future necessarily comes from an understanding of history. This understanding is also the case within the diegetic world of Blade Runner. With the creation of its sequel, memory from the first film becomes a predominant feature of the new story. The plot is divided between the film from 1982 and the sequel from 2017, each constituting a micro-narrative. Both micro-narratives deal with memory issues on their own. However, there is also an overarching plot, the macro-narrative, that encompasses and connects both films and also incorporates the memory. The macro-narrative of both films goes forward developing the story. However, it constantly loops back, referencing and integrating events from Blade Runner as pieces of the puzzle that needs completing.

The last events from the 1982 story (1) show the Blade Runner, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), and the replicant, Rachael, running away together. It is unknown to the audience where they might head or what would happen to them next. Thirty-five years later, this becomes the underlying plot for Blade Runner 2049. The opening text of the sequel (see figure 1) echoes the opening text from the original film. However, the text in the sequel reveals how much has changed in the three decades following the original story. Also set in Los Angeles, Blade Runner 2049 follows officer KD6-3.7 (Ryan Gosling); introduced during his latest mission ‘retiring’ the outlaw replicant Sapper (Dave Bautista). This mission leads him to a group of bones buried in Sapper's yard. After being analysed, the police discover these have been buried for thirty years and belong to a female replicant who died during childbirth. K's commanding officer, Lieutenant Joshi (Robin Wright), charges him with the task of locating and retiring the child. From then on, the film becomes a search for the past, not only to find the replicant but a search for K's own history as much as the replicants' fate. K's investigation takes him back to the events of Blade Runner following a trail of mediatic memory. Through it, Blade Runner 2049 examines issues of memory from various perspectives. Firstly, it continues the themes of memory and identity that were addressed in Blade Runner. Namely, the significance of real and artificial memories. Secondly, the sequel integrates 'memory' in its recollection of the previous film, both in the narrative and the dimensions of production connecting both films.

Figure 1 - Intertitles introducing Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve, prod. Alcon Entertainment/Columbia Pictures, USA, 2017)

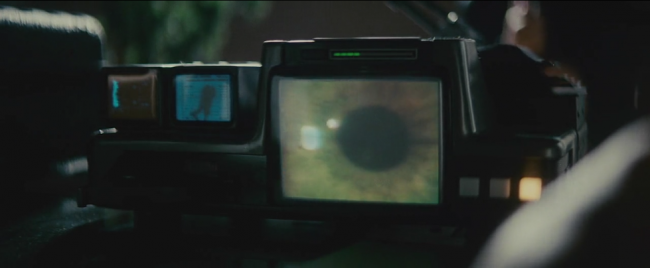

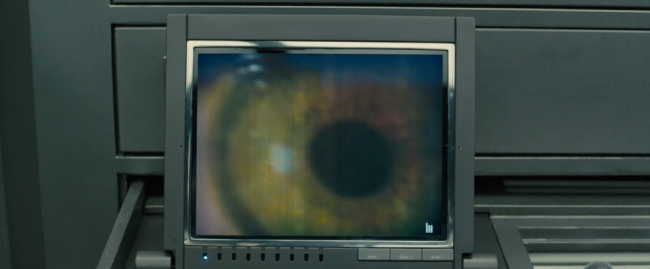

The first stop in K's mission is industrialist Niander Wallace's archives; the location of all records about replicants. This sequence shows the crucial role of the audio-visual archive in preserving memory. K needs to go deep into the library to access these records, which is depicted as an immense temple-like space filled with innovative archival technology. The immense scale of the library implies its capacity to house an "unparalleled quantity of documents" (see figure 2). In here, K finds the recording of Rachael's ‘Voight-Kampf' test from 2019. Blade Runner shows the moment when this recording was created in the diegetic past, capturing Rachael's interrogation. Blade Runner 2049 re-plays the same audio-visuals from 1982 after being preserved for thirty years: the extreme close-up of Rachael's pupil, with the audio from her interrogation with Deckard (see figure 3). These become the clues to guide K in his investigation. The significance of this recording in the film is double layered. On the one hand, it works as a memory of the diegesis, a recording inside the story world. On the other hand, it is also a memory of the real world; it is a memory of the events filmed for Blade Runner that are repurposed for the sequel. In terms of diegesis, archival memory is crucial for K's investigation. His path is guided by the different media holding the information of the past, from written records, audio recordings, video recordings and carvings in wood, to the technologies developed in this fictional future (e.g. glass spheres, holographic projections). All these media serve as scaffolding for the history and memory of past events, both preserving them and allowing K to access them. Moreover, the two levels of 1982's audio-visual media serves as a memory holder in the fictional story and the real world.

Figure 2 - Niander Wallace’s archives in Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve, prod. Alcon Entertainment/Columbia Pictures, USA, 2017)

Historian Pierre Nora has explored the archive in terms of what he calls: Lieux de mémoire, or sites of memory (Nora, 1989). For him, archives are part of a group of Lieux de mémoire (and can include libraries, museums, commemorations, and celebrations) that are “history’s most elementary tools,” “the most symbolic objects of our memory,” and “embodiments of a memorial consciousness” (ibid: 12). As I have already mentioned, memory plays a crucial role throughout the film; Blade Runner is famous for exploring how memory affects personal identity. Nora agrees with this by stating how "the quest for memory is the search for one's history" (Ibid: 13). However, Nora's attention to specific 'sites of memory' is most relevant here. He discusses how "modern memory is, above all, archival. It relies entirely on the materiality of the trace, the immediacy of the recording, the visibility of the image" (ibid). How modern memory is archival is seen throughout K's tracing of history.

Figure 3

Above: Conducting Rachael’s Voight-Kampf test in Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, prod. The Ladd Company/Shaw Brothers, USA, 1982)

Below: Monitor from Wallace’s archives showing the recording of Rachael’s Voight-Kampf test in Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve, prod. Alcon Entertainment/Columbia Pictures, USA, 2017)

Furthermore, the circumstances of Niander's collection of records speaks to what Nora calls the "privileged memory" (ibid: 12). While the historian addresses issues regarding marginalised groups, the film shows the other side of the coin. It highlights how privileged individuals have access to existing archives and control the recording of history. Niander Wallace, who acquired the remains of the bankrupt Tyrell Corporation, has a monopoly of key markets within the Blade Runner universe. Likewise, he has within his domain a vast quantity (if not the biggest) of history's records and memory. When Luv (Sylvia Hoeks) - Wallace's personal replicant assistant - refers to him as a "data hoarder," one is reminded of today's issues surrounding data surveillance and the power that data can give to their holders. Moreover, the archive is where the collective memory of society is preserved. In the end, these were the objects that allowed K to access different clues throughout his investigation and solve the mystery while, at the same time, learning more about the story of "his people." It becomes a way for peoples to preserve, access and share their past.

When we extend this understanding of memory from the individual to the collective, it is possible to see how it can significantly influence the course of society. As Niemeyer puts it, it can lead to a case of "social amnesia" where society forgets the injustices or issues of the past (Neimeyer, 2014: 4). Moreover, what we believe of the past influences what we do with the future. Hence, misremembering a particular issue or a social group leads easily to failing to build an adequate future for them. Blade Runner introduces the issues of memory distortion for the individual; from this foundation, Blade Runner 2049 talks about the significance of collective memory and social amnesia. When the police discover Rachael's bones, Lieutenant Joshi instructs K to erase every trace that could reveal the existence of the replicant child. With this, she wants to ensure the erasure of the memory of what this represents for society. She explicitly tells K that this was the way to maintain the status quo and what she calls the 'natural order of things' by separating humans from replicants. This statement is a signal example of privileged memory where a powerful individual controls what is remembered collectively.

Furthermore, during K's conversation with the record keeper, it is revealed that sometime between 2019 and 2049, a big blackout wiped massive amounts of archives and data. This complicates K's inquiry into the origin of the bones and the identity of child he is looking for. It also represents how a substantial part of the collective memory had been erased and lost. It even prevented Deckard to look for his daughter. At various times throughout the film, the characters mention 'the blackout' as a familiar collective historical event that impacted their lives; perhaps similar to how we might refer to 'the pandemic'. Talking about this blackout, the record keeper mentions to K: "Everybody remembers where they were at the blackout, you? […] I was home with my folks". This remark shows the significance of this event in the world and how it changed it. Its evocation is similar to 9/11 events, mixing the collective with individual experience and how it is recorded in memory. In a sense, this major blackout in the film’s universe is a loss of history and an enabler of social amnesia.

Contrastingly, a shared memory was the critical factor in K's transformation from a Blade Runner tasked with retiring replicants to joining the revolutionary cause for replicants' freedom. In 2049, replicants such as K are aware of their implanted memories. It is no secret to them that they do not have a long-term past; a function of a new inbuilt feature of obedience. However, this issue becomes relevant to the story when one of K's memories is linked to the investigation. A date carved on the tree next to where he finds Rachael's buried bones is the same as one carved on a wooden horse from a fictional childhood memory. This date signifies a connection between the past inside his mind and the reality of the present. It makes him wonder whether this memory might be real instead of implanted. This question is solved by Dr Ana Stelline (Carla Juri), whose work is to design the audio-visual memories implanted in the replicants' minds. She lets K know that the memory is, in fact, real. Upon learning this, K believes it means he is Rachael and Deckard's child, changing everything he knows about himself and his people. For the first time, he thinks of himself as more than just a slave created to follow orders; and so he lies to his commander and takes flight to look for his father. However, he later learns that, even if the memory is real, it was not his own but Dr Ana Stelline's. Through her work, Dr Stelline shared her memory with K, and this allowed him to understand what it was like to walk in her shoes, but most importantly, to believe himself a free, loved replicant. Learning this made him join the cause against replicants’ slave status, following what Dr Stelline states: "If you have authentic memories, you have real human responses". Bringing into the present the memory of a born replicant began to shed light on the replicants' possibility to belong in the future. The experience of the shared memory between Ana Stelline and K is likely to be shared with other replicants since she designed their memories. Taking these memories from the individual to the collective memory allowed for the cause to grow among them. In this way, the authenticity of this collective memory creates the collective human response of striving for the dignity and freedom of the replicant race.

Bibliography

Chen, I. (2011) How Accurate Are Memories of 9/11?, Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/911-memory-accuracy/ (Accessed: 8 June 2021).

Hirst, W. et al. (2009) ‘Long-term memory for the terrorist attack of September 11: flashbulb memories, event memories, and the factors that influence their retention’, Journal of experimental psychology. General, 138(2), pp. 161–176. doi: 10.1037/a0015527.

Liedl, J. (2015) ‘Tales of futures past: science fiction as a historical genre’, Rethinking History, 19(2), pp. 285–299. doi: 10.1080/13642529.2014.973710.

Niemeyer, K. (2014) Media and nostalgia: yearning for the past, present and future. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nora, P. (1989) ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, (26), pp. 7–24. doi: 10.2307/2928520.

Filmography

Scott, R. (2007) Blade Runner. Director’s cut, Widescreen version. London: Warner Home Video.

Villeneuve, D. (2017) Blade Runner 2049. USA: Alcon Entertainment and Columbia Pictures.

Footnote

(1) This writer is aware of the many different cuts and versions of Blade Runner. However, for this article I am focusing on the last chronological events of the story consistent with any of the commercially released versions.