by Nelson Correia, Edinburgh Napier University / The University of Edinburgh

The Scottish screen sector is a prolific hub for feature film, high-end TV, and factual television production, valued at more than £500 million per year, according to the national screen unit, Screen Scotland. With a freelance pool of 3,400 people across creative and craft roles, the sector has gained an international reputation for its highly skilled and adaptable workforce. Recent successes with numerous high-budget projects for the competitive global entertainment market range from Hollywood blockbusters, including Fast & Furious 9 (2021) and the new Indiana Jones movie (in postproduction), to productions for streaming platforms, such as the Highland fantasy series Outlander (2014–).

It took four decades for the sector to reach its current state of talent development, and this trajectory has largely been propelled by the arrival of Channel 4 in 1982. Prior to that, screen production activity in Scotland had been fairly limited. The institutional landscape to foster indigenous filmmaking had yet to be developed, and the local freelance workforce was modest in numbers. Channel 4 from the outset proved to be a crucial source of finance to kickstart production in Scotland, bringing a new array of employment opportunities across the local sector.

In the 1970s, the freelance screen workforce in Scotland consisted of a small cluster of at most 70 film crew personnel, working in a few key creative and technical roles. This workforce started to form in the 1930s and since then had been involved almost exclusively in the production of sponsored short documentaries for local cinema screening, mostly commissioned by government and industry. This mode of production, however, was becoming unsustainable by the mid-'70s due to the resistance of audiences and exhibitors to sponsored content. At the same time Scottish producers had to compete for available work with London-based production companies, who on being awarded government contracts would fly entire crews from south of the border to shoot in Scotland.

Nevertheless, there were no alternatives in sight. In the film sector there were no local structures to fund any other form of indigenous production. As for television, local programme output, by BBC Scotland and the two regional ITV licensees, Scottish Television (STV) and Grampian Television, was simply not sufficient to require freelance workers on a regular basis. This limited freelance employment opportunities to occasional stand-ins for contracted staff on sick leave or holiday. In addition, strict regulations enforced by a pre-entry closed shop union, the ACTT (Association of Cinema and Television Technicians), made crossover between the two sectors very difficult.

Yet, many Scottish freelancers had ambitions to venture into feature film and television production. The work on sponsored documentaries had been a training ground for various individuals, including directors Bill Forsyth, Charles Gormley and Murray Grigor, some of whom would later become household names. Some of these professionals eventually formed their own production companies during the 1970s, which in turn provided fertile conditions for the emergence of a new generation of freelancers keen to venture into bigger-budget projects. So, in this spirit, Scottish freelancers and producers decided to come together to campaign for more opportunities.

Their effort led to the Film Bang manifesto, calling for new mechanisms for production funding and institutional support for the local sector. The campaign was launched in a two-day public conference, held in January 1976 at the Glasgow Film Theatre and organised by an ad-hoc sub-committee of the ACTT union’s Scottish freelance branch. The event also saw the launch of the Film Bang directory, a 60-page booklet containing editorial articles and listings of freelance personnel, production companies and filming facilities around Scotland. A second edition was published in 1978, followed by roughly biennial publications until 1986 when Film Bang became an annual directory (published to this day, both on paper and online).

Published from 1976 to this day, Film Bang has become a reference point for the Scottish screen sector and has the potential to provide robust longitudinal evidence to help track the evolution of the local freelance workforce.

This mobilisation continued through the following years, gaining support from academics, cultural agencies, and lobbying groups on both sides of the border. By the turn of 1970s the first public interventions started to materialise, including the creation of an entry-level training programme in 1978, the Film Technician Training Scheme, and the establishment of the Scottish Film Production Fund (SFPF) in 1982, with a modest annual budget of £80,000 from the Scottish Arts Council and Scottish Film Council to support fictional productions. The climate was optimistic and rapidly changing. Funding, however, was still scarce.

Channel 4 was the godsend the sector needed. The new broadcaster emerged as one of the main sources of finance in Scotland at the time. It placed commissions across formats and genres to local producers, thus broadening the scope for freelance employment in the local sector. Channel 4 offered Scottish-based freelancers the chance to break into feature film and television production, and then created conditions for the expansion and skills diversification of the workforce.

Channel 4 also helped with new talent development. Many of the broadcaster’s early Scottish commissions employed trainees and beginners alongside experienced crews, enabling the transfer of skills. And, even though it never paid regular subventions to the official Scottish training schemes of the time, the Channel supported alternative access routes to the local industry, including the production of short films made by newcomers, and projects from the workshop movement, such as the documentaries Northern Front (1986) and Leithers (1988) by the Edinburgh Workshop Trust, and the drama The Priest and The Pirate (1994) by the Video in Pilton group.

The respective ways in which Scottish freelancers were involved in feature film and television projects were slightly different. In television, opportunities were more immediate, especially on documentaries and current affairs. TV commissions were not exactly abundant and normally consisted of one-off projects with small crews. However, they were constant enough to provide regular work to freelancers across departments and keep the workforce going. There was also frequent work available on educational programmes for the Channel 4 Schools service and on long-running factual shows, including the magazines Years Ahead (1982–1989) and Halfway to Paradise (1988–1994), which throughout the years counted on the collaboration of numerous professionals across the local sector.

To a lesser extent there were also opportunities in the production of drama series (even if not on the same level as those offered by STV and BBC Scotland, who throughout the 1980s and 1990s expanded their drama departments). Nonetheless, the few Channel 4 Scottish series of the time, such as Blood Red Roses (1986) and Brond (1987), were important for the career development of many freelancers. One of them was producer David Brown, then a newcomer, who decades later would become the executive producer of the global hit series Outlander.

In terms of feature film, the commissions from the 1980s and '90s included various large-scale projects, which helped stimulate demand in Scotland for new job roles and specialised skills in both creative and craft areas. Among them, the first Scottish features with budgets over £1 million, Heavenly Pursuits (1985) and Venus Peter (1989), as well as the global box-office hits Shallow Grave (1994) and Trainspotting (1995). The involvement of local crews in film projects, however, was not as immediate as in television projects. It happened more gradually and varied from production to production.

An advert from the 1984-85 Film Bang directory: While south of the border Channel 4 has helped to revitalise an already existing industry, in Scotland it has been closely linked to the birth of what can be considered a ‘Scottish film industry’.

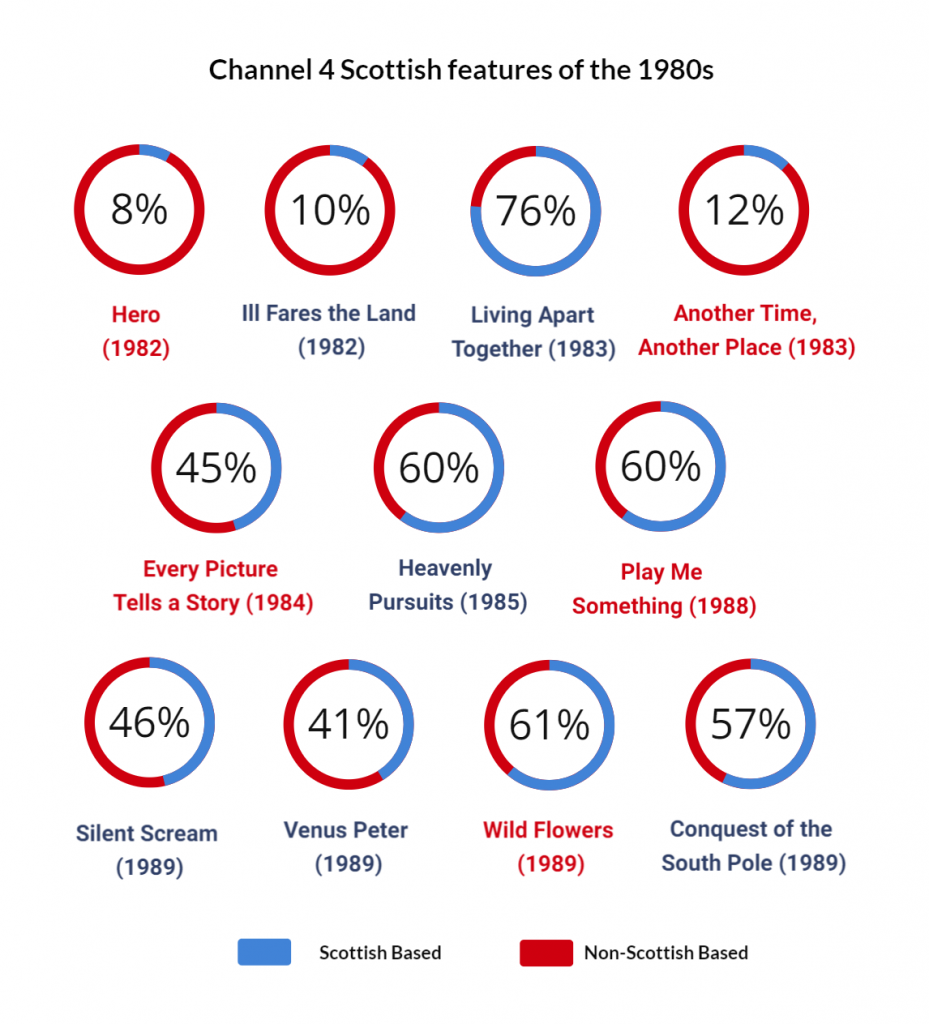

A comparative analysis of the crew credits list from Channel 4’s Scottish projects of the 1980s perfectly illustrates the initial patterns and trends of workforce development across the local sector. Of the 19 Scottish features intended for theatrical release and/or terrestrial broadcast throughout the decade, 11 had the financial involvement of the broadcaster. Despite having Scottish themes, locations and cast, many of these projects were totally or partially managed by London-based production companies and brought opportunities for personnel based both within and outwith Scotland.

In the first batch of commissions for the Film on Four slot, between 1982 and 1983, the majority of features were produced and shot by London-based crews. Only one out of four projects had predominantly Scottish-based personnel, Charles Gormley’s Living Apart Together (1983). In the others, the number of local crews was notably low. One of these projects, Hero (1982) by English director Barney Platts-Mills, lists only two Scottish-based personnel in its main credits. The homebases of crews, moreover, reflect the locations of the producers (on both sides of the border).

However, as the 1980s progressed there was an increase in projects by Scottish producers and, consequently, employing more Scottish-based crews. Then, towards the end of the decade, projects led by London companies started to show a mixture of Scottish-based and non-Scottish-based personnel. Notably, in the early '80s the Scottish freelance pool was not very extensive and lacked expertise in many areas associated with narrative features (e.g., art, costume and postproduction), but over the decade the workforce began to expand, and new roles started to be performed by local personnel. In addition, various Scottish-based freelancers appeared in different productions throughout the decade. Some also progressed from entry-level to more senior roles, which may suggest the emergence of local patterns of career sustainability and progression.

The involvement of Scottish-based crews in the Channel 4 Scottish features of the 1980s: In the circles, blue indicates individuals based in Scotland and red individuals based outside Scotland. Production titles in blue correspond to Scottish-led projects and in red to projects controlled by London-based production companies

While it is possible to consider the evolution of the Scottish workforce as a whole, the pace of skills development across production departments varied. For example, in art-related roles, costume, hair, and make-up there was an initial predominance of non-Scottish-based crews until the mid-'80s, after which most of these personnel became locally based. This suggests that these specialisms developed over time. Postproduction, on the other hand, was a particularly hard area for Scottish freelancers to break into. Across the 1980s, editors were mostly London-based, and in dubbing (re-recording and mixing) all projects employed crews from outside Scotland. It should be noted that during this period there was a lack of postproduction facilities in Scotland. The 1990 Film Bang directory lists only one sound studio and one cutting room.

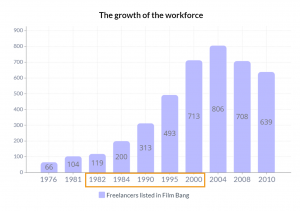

The expansion and skills diversification of the Scottish workforce during the early Channel 4 period can be traced through the annual Film Bang listings. In both areas the path of development coincided pretty much with the trajectory of the broadcaster. In terms of numbers, there was a sharp increase in freelancers listed in the directory throughout the 1980s and 1990s (from 104 individuals in 1981 to 713 in 2000). Growth began as soon as Channel 4 arrived and started commissioning in Scotland. As the number of commissions and scale of the projects increased by the mid-1990s, so did the freelance workforce.

Freelancers listed in the Film Bang directory over time: A Sharp increase in the workforce is observed during the early Channel 4 period, between 1982 and the early 2000s.

In terms of skills development, Film Bang gradually introduced new areas of specialism corresponding to the requirements of Channel 4-backed projects. In 1990, for example, job roles became more specialised (e.g., Steadicam operator; script supervisor; casting director). There were also new senior and junior roles (e.g., art department assistant; wardrobe supervisor), as well as broadcasting-specific occupations (e.g., vision mixer; autocue operator). From the middle of the 1990s, there were even higher levels of specialisation, as job roles started to reflect the skills profiles and traditional hierarchical structures of large feature film productions, similar to some of those from Channel 4 (e.g., line producer; location assistant; first, second and third assistant director).

Since this early period of Channel 4 commissions the Scottish-based freelance pool has changed significantly in terms of numbers, skillsets and organisation. Channel 4, evidently, was not responsible for this alone. Other funders emerged over time, broadening this transformation. Channel 4, nonetheless, offered the fundamental conditions to kickstart, then sustain this process. Many parallels can be traced between the Scottish sector of 1982 and today. Once more the freelance workforce is expanding and facing the challenge of upskilling to meet the requirements of a fast-changing sector. In the same way that Channel 4 enabled many 1980s and 1990s professionals to expand their skills and break into new areas of production, it today supports current freelancers in developing their careers across further genres and formats, through initiatives such as the C4 Indie Growth Fund and the establishment of a new Creative Hub in Glasgow in 2019. This reminds us that Channel 4 has not only had, but continues to have, a vital role in fostering screen-sector talent in Scotland.

About the Author

Nelson Correia is a PhD researcher investigating the development of the freelance screen workforce in Scotland over the last half-century. His project is a collaboration among Edinburgh Napier University, the University of Edinburgh, and the National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive, with a scholarship from the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities (SGSAH). He previously worked in broadcast journalism and factual television production.