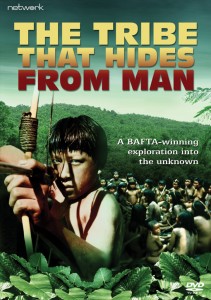

Adrian Cowell’s award-winning 1970 documentary The Tribe That Hides From Man about the Kreen-Akrore Indians is now available on DVD. Dr Elizabeth Ewart of the University of Oxford has gone to Brazil to watch the film with the original tribe and examines its complex legacy.

About the author: Dr Elizabeth Ewart is a lecturer in the anthropology of Lowland South America at at the University of Oxford. She obtained her PhD from the London School of Economics, University of London in 2000. Her research is with indigenous people in Central Brazil where she has lived and worked with Panará people. Her doctoral research focused on Panará concepts of self and other by examining the relationships between Panará people and other indigenous groups of the area as well as non-indigenous people. Her publications include: Body Arts and Modernity (2007) and Space and Society in Central Brazil: A Panará Ethnography (2013).

About the author: Dr Elizabeth Ewart is a lecturer in the anthropology of Lowland South America at at the University of Oxford. She obtained her PhD from the London School of Economics, University of London in 2000. Her research is with indigenous people in Central Brazil where she has lived and worked with Panará people. Her doctoral research focused on Panará concepts of self and other by examining the relationships between Panará people and other indigenous groups of the area as well as non-indigenous people. Her publications include: Body Arts and Modernity (2007) and Space and Society in Central Brazil: A Panará Ethnography (2013).

Throughout the mid to late 20th century the Government of Brazil pursued a policy of contacting isolated indigenous groups in Amazonia in order to access the resources of the vast Brazilian interior. In 1967 a road was being built linking the city of Cuiaba to the south of the Amazon rainforest with the port city of Santarem on the Amazon river to the north. It was known that this road would cut through territory inhabited by apparently hostile Indians who only six years before had killed an English man. The decision was therefore taken by the Brazilian government to establish peaceful contact with Indians known as Kreen-Akrore. Two remarkable brothers from São Paulo, Claudio and Orlando Villas Boas led this expedition to meet and pacify these people, rumoured by some to be giant Indians. They had previously founded the Xingú Indgenous Peoples’ park, a vast area along both sides of the upper and middle Xingú, inhabited by numerous indigenous groups which was to become home to several more, displaced from their original lands after contact with Brazilian national society.

Photo: Dr Elizabeth Ewart

The expedition and the Villas Boas’ vision of pacification of the Kreen-Akrore is the central focus of Adrian Cowell’s documentary film, The Tribe That Hides From Man (1970), yet it does much more than this. The film also documents the ideals behind the formation of the Xingú Indigenous Peoples Park and finally it also provides striking footage of indigenous family life, hunting skills and raiding practices.

Divided into three parts, the first part describes the Xingú Park and some of the people living there. For most indigenous groups contact with non-indigenous people has in the first instance meant disaster, since diseases such as measles and flu quickly killed vast numbers of people. And though the indigenous population in Brazil is now growing more rapidly than the overall Brazilian population, huge numbers of indigenous people within Central Brazil were to die in the years after their first sustained contacts with non-indigenous people.

The second part of the film shows the preparations for the contact expedition with the Villas Boas brothers making visits to two Kayapo groups, one of which had only recently raided the Kreen-Akrore and had captured four children. In the film the Kayapo re-enact the raid in which 26 people were killed and four children captured. This part also contains some beautiful and now rare footage of traditional Kayapo hunting practices.

The second part of the film shows the preparations for the contact expedition with the Villas Boas brothers making visits to two Kayapo groups, one of which had only recently raided the Kreen-Akrore and had captured four children. In the film the Kayapo re-enact the raid in which 26 people were killed and four children captured. This part also contains some beautiful and now rare footage of traditional Kayapo hunting practices.

In the third part the tension rises as the expedition advances on the Kreen-Akrore, slowly but surely coming closer, hanging presents of steel axes, aluminium cooking pots and glass beads in the forest for the Indians to take. As we follow the Villas Boas brothers into villages abandoned minutes before by the Kreen-Akrore, and as the camera scans the impenetrable forest, the sense of being watched, of trying to see people who might be out of sight just meters away is palpable.

In August of 2007, I sat with the people formerly known as Kreen-Akrore - who now call themselves Panará - and watched The Tribe That Hides From Man. Today they number some 300 individuals among whom are several older men and women who vividly remember the time when the white people were following them through the forest leaving steel axes, machetes, pots, pans, beads and mirrors for them to find. But they also remember what happened afterwards. When the Villas Boas brothers finally did establish contact in 1973 the Panará were almost instantly gripped by massive influenza epidemics that spread through their population like wildfire and killed 70- 90% of the population within the space of two years. The Cuiaba-Santarem highway cut through their territory and in 1975 the decision was taken to move them to the Xingú park, a decision which is in fact predicted in Cowell’s film. Seventy-nine survivors of a pre-contact population of between 450 and 600 people were flown to the Xingú park some 250 kilometres away. However, unlike all the other groups in the Xingú, the Panará refused to adapt to their new ‘home’ and never gave up their memories of the lands they had left behind. In 1994 they took the unprecedented decision to leave the Xingú park and to move back to a small part of their former territory which at that time remained untouched, the vast majority of the land having long since been devastated by open-cast gold mining. By 1997 the move was complete and in 2003 the Panará won a long drawn out court case against the Brazilian government claiming damages for loss of land and life during the contact era.

The dramatic tension conveyed by the cinematography, the sometimes almost lyrical commentary and the very subject matter make this a unique and extraordinary film. Today a number of Brazilian indigenous groups remain isolated, refusing to make contact with Brazilian national society but nowadays these groups are largely left in peace.

Youths and elders during a workshop on recent Panará history constructing a model of a Panará house (photo: Dr Elizabeth Ewart)

The Tribe That Hides From Man is a documentary that needs to be understood in the context of its time. In those days, it was perhaps more common to talk about indigenous people in terms of ‘primitives’. Just as Cowell and indeed the Villas Boas brothers were sure that their contact would inevitably spell the end of Panará society so they were also convinced that the ‘laws of evolution’ dictated that Panará people would inevitably become a little more like us with every steel axe and every aluminium pot that they accepted. That this has not happened, and that indigenous people today have not been simply swallowed up by the forces of Western globalisation is a tribute to their resilience and sophistication in the face of sometimes almost overwhelming odds.

Dr Elizabeth Ewart