by Eva Dieteren

International discussions on migration and integration regularly single out migrant men as a dangerous group, a threat to national safety. In the Netherlands, these debates are often targeted towards migrant men from one specific nationality, namely Moroccans (Roggeband & van der Haar, 2018). One of the key political figures in these debates is Geert Wilders, party leader of the Party for Freedom. He views Islam and migration as threats to safety and Dutch national identity and proposes the closing of mosques, a ban on veils, and other similar measures (Roggeband & van der Haar, 2018). Over the past decade, he has sparked up controversy with his remarks specifically targeted towards Dutch-Moroccans. Debates revolving around migration and integration are reflected in media, not merely in news segments but also within popular culture.

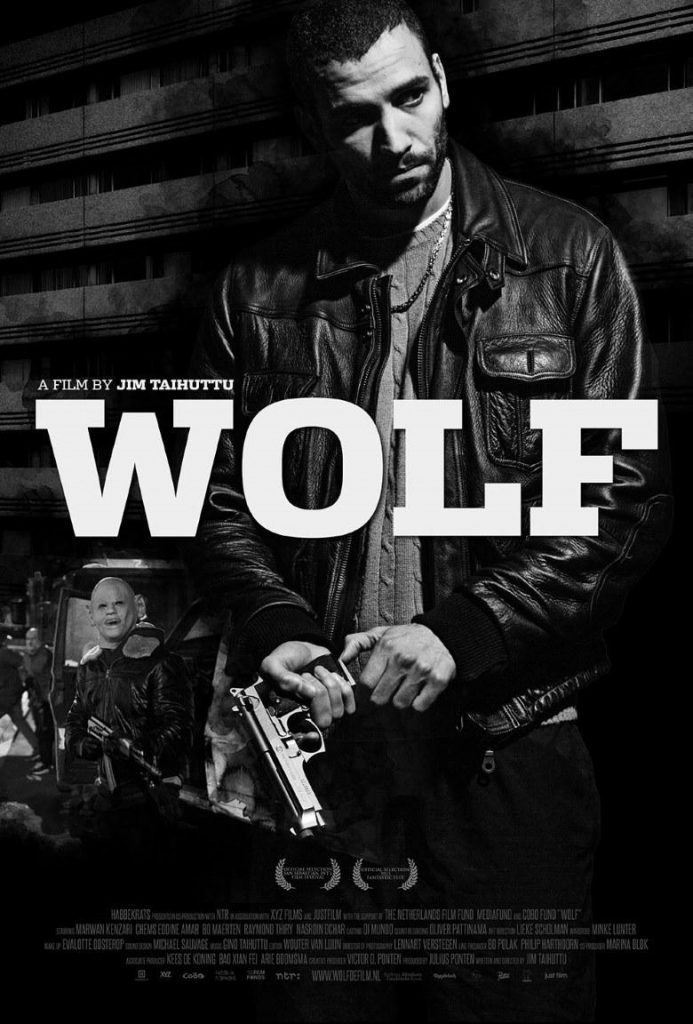

In Dutch media, Moroccan men are often represented through violent stereotypes. In general, political debates often focus on Moroccan youngsters in relation to violence and petty crimes, and this stereotypical representation is prevalent in Dutch popular culture through films and television shows such as Gangsterboys and Mocro Maffia. Dutch film director Jim Taihuttu has been at the forefront of creating films that focus on Moroccan men and their experience of integrating in the Netherlands. His film Wolf (2013) has been praised for its raw depiction of Moroccan men, living in ghetto areas in the Netherlands (Moorman, 2013). I will take a closer look at Wolf and the ways in which Moroccan masculinities are depicted.

Wolf FIlm Poster

Wolf follows Majid as he has just been released from prison and struggles to navigate between a life of professional boxing and organised crime (Ponten & Taihuttu, 2013). He becomes involved with a Turkish gang and its leader Hakan. His best friend Adil is not satisfied with the petty crimes they commit and plans bigger criminal operations. Violence is central in Wolf, as most of the aspects of Majid’s life are invested with either legitimate forms of violence, such as boxing, or illegitimate forms, such as domestic violence and gang violence. The lines between these two forms become blurred throughout the film. Through boxing, Majid becomes involved in the world of organised crime, as Hakan’s gang is involved in betting on boxing matches. Throughout the film, there are various moments where Majid’s violent outbursts seem irrational, where he either continues to beat someone who is already unconscious or where he initiates a fight with someone.

In order to look at the ways in which masculinity is performed in Wolf, it is important to establish a definition of masculinity and explore its relation to violence. Masculinities by Raewyn Connell (1995) can be seen as a foundational text in masculinity studies, which sets out to exemplify that there is no such thing as a singular notion of masculinity. By focusing on masculinities one can account for the diversity of forms of masculinity that are constantly in conversation with each other and as such are fluid and subject to constant alteration. The relationship between varieties of masculinity is “constructed through practices that exclude and include” and as such are “relations of alliance, dominance and subordination” (Connell, 1995, p. 37). Connell brings forward an important concept with regards to this relationship: hegemonic masculinity, which refers to the form of masculinity that occupies a hegemonic position in a specific time and place. She opposes the concept of hegemonic masculinity with that of marginalised masculinity, taking into account structures of race and class.

Still from Wolf

One of the ways in which the relation between masculinity and violence can be explored is through linking Connell’s work to Franz Fanon’s work on violence. In his book The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon (1961/2001) explores the relationship between the coloniser and the colonised and argues that violence is an integral part of this relationship as it is through violence that the colonised finds freedom. The colonial situation is structured according to a Manichean order, invested in binary oppositions of good and evil, civilised and uncivilised. In this fashion, the colonised gets dehumanised, turned into an animal. He lives in a world of opposition, where he gazes at the coloniser and his town with envy, dreaming of possession. Dreaming of going beyond the limits of the Manichean order and taking over the coloniser’s position. However, what is remarkable about the native figure is that it does not directly aim this aggression towards the settler. Instead, it is, at first, manifested against his own people. Even though Fanon’s work focuses on processes of decolonisation, it is still relevant in contemporary contexts as Manichean discourses on coloniser and colonised, on self and other, mirror the ways in which contemporary racial politics polarise different ethnicities.

One of the interesting aspects of combining the work of Connell and Fanon is their exploration on encounters and interactions. It is through interactions with others that masculinities are constituted, Manichean orders are constructed, and violence is performed. In Wolf, Majid’s closest relationships with men are invested in variations of violence. Majid’s close group of friends exemplifies bonds that foster forms of hypermasculinity, specifically his relationship with his best friend Adil. In this context, hypermasculinity refers mainly to physical strength and dominance over others. Majid and Adil have a complicated bond that is fuelled simultaneously by admiration and envy. As Majid is physically stronger than Adil, he is instantly more respected by other men. Adil tries to make up for his lack of physical strength by wanting to excel in bigger crimes and by acquiring guns. Another way that Adil tries to portray his dominance over Majid is through sexual achievements, by attempting to steal Majid’s girl, Tessa. Tessa becomes a symbol of male dominance, as a significant amount of violent scenes revolve around her ‘possession’.

These hypermasculine performances are contrasted, however, by Hamza, Majid’s brother who is hospitalised. One of the ways in which this contrast between Hamza and Majid could be interpreted is through Hamza’s illness, which has made him weak and this is reflected by his interaction with Majid: he speaks slowly and calm. His appearance also opposes that of Majid, and this is partly due to his illness. His bald head and hospital clothes make him appear ‘whiter’ than Majid, who has a beard and wears dark clothes. However, besides his illness, Hamza is portrayed as an anomaly, an example of a successfully integrated Moroccan. He does not have an accent and does not use slang. Whereas dominance with other characters in Wolf revolves around physical and territorial dominance through violence, Hamza represents a more bourgeois, capitalist form: intellectual and economic dominance. This mainly becomes evident in the scene where Majid goes to Hamza’s apartment. As opposed to the ghetto space, Hamza’s spacious, modern apartment is located in a shopping street. As Majid is walking through the apartment, several close-up shots reveal more about Hamza’s intellectual and economic status. Hamza’s study books and suits suggest that he has studied and likely had a corporate job. This scene could be interpreted as symbolising Hamza’s integrated life and consequently, Majid’s desire of this lifestyle that he cannot obtain. The latter is represented through Majid trying on Hamza’s suits and looking at himself in the mirror. The apartment represents a life that Majid potentially could have had if he had diplomas and incorporated a similar lifestyle as Hamza.

Hamza’s intellectual and economic dominance is symbolised through his apartment and this reflects the importance of space in the construction of masculinities. The spaces that Hamza occupies are opposed to the ghetto and as such, can foster alternative performances of masculinity. In general, the city greatly contributes to the construction of identities as it offers “spaces of encounter, exchange, movement where people from an array of different places and cultures live and work in close proximity.” (Cherry, 2017, p. 145). Movement within cities and interaction between men are essential for the construction of masculinities, as different performances are observed, contrasted, and reformulated (Connell, 1995). The story of Wolf is located in an unidentified ‘ghetto’ neighbourhood in the Netherlands. Similar to Fanon’s (1961/2001) colonised town, it is a place without spaciousness, characterised by blocks of flats and concrete walls covered by graffiti. It is a place filled with poverty and crime, where marginalised masculinities function in its own set of hierarchies. The majority of the scenes in Wolf, and primarily the ones including encounters between different men, are situated on the streets. What is remarkable about the space in Wolf is that its location is never explicitly specified. This provides a sense of universality, indicating that these spaces and the masculinities they foster can exist anywhere.

Another cinematographic element that creates the sense of universality is the decision to shoot the film in black-and-white, which I interpret as emphasising the ghetto’s Manichean order. It marks a clear, binary distinction between Majid and Hamza, as one’s world is filled with darkness and the other’s with light. Besides this, black- and-white symbolises quite literally a world without colour, a world without happiness and that is not in any way glamorised. Throughout the film, the ghetto is depicted through scenes on balconies and rooftops, presenting the characters overlooking the space and expressing their dreams of possession and domination.

Jim Taihuttu

The alternative space that Hamza occupies in Wolf is a key element to the performance of his masculinity. The crucial argument behind his characterisation that I want to put forward is that his performance of non-violent masculinity – and with it its intellectual and economic domination – is rendered possible through his negation of the ghetto space. As the ghetto is fuelled by violence, it does not provide a space for the construction of other masculinities. One could say that in the ghetto, violence is inevitable and inescapable. Wherever Majid goes, his encounters are invested with some form of violence, whether this is through boxing or organised crime. The only manner in which Majid can escape violence is when he escapes the space and instead, vicariously takes on his brother’s life as he situates himself in Hamza’s space – his apartment. When Majid visit Hamza’s apartment, his movements signal a desire of possession – trying on Hamza’s clothes, scrolling through his books.

Nevertheless, it is clear that while Majid can dream of a similar life as Hamza’s, he cannot realise this due to his entanglement with the ghetto space. He does not have the means necessary to acquire Hamza’s intellectual and economic ‘bourgeois’ lifestyle, such as diplomas or the money to move away from the ghetto. Hamza’s death symbolises Majid’s faith. He can no longer escape the ghetto, as he no longer has access to Hamza’s ‘alternative’ spaces. The characterisation of Hamza sheds light on the importance of space and class in the construction of masculinities. I consider these elements to be vital to the violent performances of masculinity by characters such as Majid. Violence is tied to the space and the masculinities that it fosters.

Moroccans are often singled out by Dutch politicians and media as a problematic group due to their violent and criminal behaviour. Wolf shows that violent performances of masculinities are inextricably linked to the spaces in which these identities are constructed. Violence appears to be inevitable and inescapable in the ghetto where Majid lives. Majid’s movement through the ghetto, and the interactions that he has with other masculinities, shape his own performance of masculinity and specifically trigger his violent outbursts. Violence is used to assert dominance over others. In order to escape the violence, one would have to become distanced from the masculinities present in the ghetto by removing oneself from the space and incorporating a more bourgeois lifestyle. This performance of masculinity is represented by Hamza, as he represents a different form of dominance. However, if one is not able to escape the ghetto through intellectual or economic measures, violence becomes an inevitable fixture within the performance of masculinity. What this exemplifies is that, whilst Dutch media and politicians often use nationality as a signifier for violent behaviour, Wolf brings attention to the central structures of space and class in these identity formations. Violence is not something that is inherent in Moroccan men, or even in Muslim men. Violence becomes a means of interacting within the space of the ghetto.

About the Author:

Eva Dieteren enjoys studying the representation of gender, sexuality and race in contemporary popular culture. Following her Bachelor’s degree at Maastricht University with a semester abroad at UC Santa Cruz, she is now completing her post-grad at the University of Edinburgh and exploring the representation of the cyborg in the artwork of Janelle Monáe for her Master’s dissertation in Gender and Culture.

References:

Cherry, P. (2017). British Muslim Masculinities in Transcultural Literature and Film (1985- 2012) [PhD Dissertation]. University of Edinburgh.

Connell, R. (1995). Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fanon, F., & Farrington, C. (Trans.) (2001). The Wretched of The Earth (Penguin classics). London: Penguin (Original work published in 1961).

Moorman, M. (2013, September 18). De verwachtingen voor Wolf waren hooggespannen en worden meer dan waargemaakt [The expectations for Wolf were high and are more than fulfilled]. Het Parool. Retrieved from https://www.parool.nl/recensies/de-verwachtingen-voor-wolf-waren-hooggespannen-en-worden-meer-dan-waargemaakt~a3511819/

Ponten, J. (Producer) & Taihuttu, J. (Director). (2013). Wolf [Motion Picture]. The Netherlands: Habbekrats.

Roggeband, C., & Der Haar, M. (2018). “Moroccan youngsters”: Category politics in the Netherlands. International Migration, 56(4), 79-95