A vivid visual reconstruction can help to express the complex findings of archaeologists and historians in an accessible, engaging way. Dr Matthew Nicholls, University of Reading, presents his own work in the field.

About the Author: Dr Matthew Nicholls is Associate Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Reading. Matthew currently teaches CL2RE Roman Empire and CL3RC Roman Cities. These courses reflect his interest in the political and social history of the Romans and the way that the built environments of Rome and cities around the empire expressed their values and priorities. He also directs Reading's unique City of Rome MA programme and provides much of the teaching for it, alongside Dr Annalisa Marzano and other colleagues. Matthew is currently working on a book on public libraries in the Roman world for Oxford University Press. His publications include:. 30-second Ancient Rome (Ivy Press, 2014).

About the Author: Dr Matthew Nicholls is Associate Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Reading. Matthew currently teaches CL2RE Roman Empire and CL3RC Roman Cities. These courses reflect his interest in the political and social history of the Romans and the way that the built environments of Rome and cities around the empire expressed their values and priorities. He also directs Reading's unique City of Rome MA programme and provides much of the teaching for it, alongside Dr Annalisa Marzano and other colleagues. Matthew is currently working on a book on public libraries in the Roman world for Oxford University Press. His publications include:. 30-second Ancient Rome (Ivy Press, 2014).

I research and teach the history of ancient Rome, and Roman architecture, at the University of Reading. This is naturally a very visual subject. From the grandest public monuments of the Forum and Palatine to the everyday back streets, warehouses, and multi-storey apartments of the ancient city, the archaeological source material lends itself to visual study and interpretation. Reconstructing the way this enormous, complex city appeared and functioned has always been a goal of archaeologists and ancient historians, and visual methods - from archaeological plans to watercolours to physical models in plaster and cork - have long been part of their repertoire.

… students, familiar with high-quality visualisations, respond particularly well to immersive 3D reconstructions used as learning tools

Visiting Rome in person is the best way to get a sense of the city’s history, and over the years I have led several study trips around its sites. Such trips are not possible for everyone, though, and the city’s ruins do sometimes need interpretation – students or tourists can find the remains impressive but confusing. Black and white line illustrations or archaeological plans, which tend to be used by existing archaeological guides to the city, are helpful but can be difficult for non-specialists to interpret or match to what they see on the ground. Both on site and back in the classroom or library, a vivid visual reconstruction can help to express the complex findings of archaeologists and historians in an accessible, engaging way. Today’s students, familiar with high-quality visualisations from film, computer games, and television, respond particularly well to immersive 3D reconstructions used as learning tools.

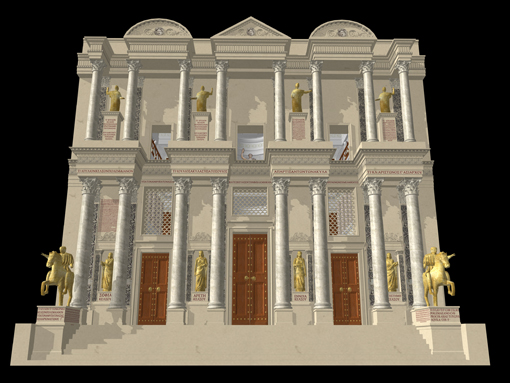

Digital modelling now offers a powerful new way of creating this sort of visual material, increasingly accessible to those who, like me, have no formal background in digital graphics work. I began to experiment with digital reconstruction during my DPhil work at Oxford, using free and easily-learned modelling software like SketchUp to create digital representations of individual structures that I was working on. In particular I wanted to illustrate how I thought ancient public library buildings functioned – how they appeared to visitors, where the book scrolls were kept – and for this purpose pictures were at least as useful as written descriptions.

The Library of Celsus, Ephesus. Modern Austrian archaeologists have re-erected the facade, and this digital model adds interior and exterior features. (image © Dr Matthew Nicholls)

My early experiences with modeling software were very positive. The process of making these digital models is similar to drawing in a three-dimensional space on screen, using a good set of fairly intuitive tools, with more complex functions waiting to be discovered as one’s skills develop. I found it relatively straightforward to pick up and, indeed, almost addictively good fun. Before long I was producing useful digital content that I could use to generate still or moving images to illustrate talks, lectures, and publications.

When I moved on to Reading, and began running its MA in the City of Rome, I wanted to carry on using digital reconstruction and developed the rather ambitious goal of creating a digital model of the entire ancient city. I had plenty to learn along the way, expanding my expertise to take in assembling, texturing, lighting, and rendering complex scenes, but the model - or at least, the first version of it - is now complete.

My model aims to show the entire city as I think it looked around AD315, the epoch when the widest variety of great monuments coexisted before the city and its empire declined and collapsed. The buildings can of course all be taken out and viewed in isolation - which is why they all look (deceptively) ‘brand new’ - but I like it best when the model is viewed and explored as a whole city. Rome’s topography, its famous hills (actually rather more than seven) and the Tiber river, provided the space for centuries and centuries of continuous building and rebuilding; hills were extended and terraced, and valleys drained and filled, as the city grew. By locating individual monuments in this complex landscape of natural and man-made features, it is possible to see not only how they worked as individual structures but, importantly, how they relate to and interact with each other, and how the meaning of the grand monuments is affected by their location and visibility among the less glamorous residential and commercial districts of the working city.

The fact that one can place a virtual ‘camera’ anywhere within the model means that the viewpoint can easily be changed to achieve these ends. Sometimes the best way to illustrate a point is hovering above the city in a ‘gods’-eye view’ that no ancient Roman could ever have seen; for other purposes, a view at or near street level shows us how the city’s buildings appeared to its ancient inhabitants. The ability to adjust both viewpoint and lighting parameters means that it is possible to use the model for research enquiries as well as for teaching tool. For example, I am currently investigating the visual experience of taking different routes through the ancient city, and the lighting and shadowing conditions in certain buildings at different times of the day and year.

Forum Augustum inside portico

The emperor Augustus built this splendid Forum to celebrate his new regime's power, wealth, and lineage. The colourful marbles used came from across Rome's expanding empire (image © Dr Matthew Nicholls)

A project like this has to draw on many different types of evidence, from the study of archaeological remains to literary accounts and inscriptions and the tantalizing surviving fragments of the Forma Urbis, a giant marble map of the city made in the early 3rd century AD. Where specific evidence is lacking - as for large areas of the city’s residential districts, which survived and were documented less well than the grand monuments - a measure of (educated) guesswork is needed, with analogy on the basis of what evidence does survive. Handling this range of evidence and its interpretation is a familiar part of the academic discipline of ancient history, but digital modelling is a new way of articulating and presenting historical enquiry, both for teaching and research.

This combination of a relatively new visual, digital medium with traditional disciplinary research skills appeals to students. After using my digital work in teaching, and explaining how I had made it, I found that our undergraduate and postgraduate students wanted to try it for themselves. To enable them to do this, I developed a new third-year undergraduate module, called ‘Digital Silchester’, which they can take as part of their degrees in Classics, Ancient History, or Classical Studies. The aim is to research and create a digital model of a building from our local Roman site of Silchester (excavated over the last twenty years by our own Archaeology Department), using free SketchUp modelling software. The chance to gain academic credit in an innovative digital, visual medium rather than a conventional essay or exam answer appeals strongly to many students, and I have seen some very imaginative and successful models made after a single term’s tuition.

My own digital work, meanwhile, has appeared in Discovery Channel and BBC documentaries, in BBC History Magazine, History Today, National Geographic Storica, and other popular publications; I am also currently writing a book based on it for Cambridge University Press. With recognition in the 2013 BUFVC Learning on Screen Awards, and as the winner of the 2014 national Guardian Higher Education Award for Teaching Excellence, I hope this project shows that digital visualisation can contribute a lot to research and teaching practice, even for academics and students without previous experience. Download some software and give it a go!

Dr Matthew Nicholls www.reading.ac.uk/classics/research/Virtual-Rome.aspx