2012. GB. Blu-ray/DVD . 117 minutes (+ extras). Eureka (Masters of Cinema series). Certificate 15. Price £22.99

About the Author: Robert S. C. Gordon teaches Italian cinema at Cambridge University. He has published widely on 20th-century Italian literature, cinema and cultural history. He is the author or editor of several books on the work of Primo Levi, including Primo Levi's Ordinary Virtues, Auschwitz Report and The Cambridge Companion to Primo Levi. He is co-editor of Culture, Censorship and the State in 20th-Century Italy and his study of cultural responses to the Holocaust in Italy will appear in 2012. His work on cinema includes Pasolini. Forms of Subjectivity (1996) and Bicycle Thieves (2008), DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries on Pasolini's Teorema and De Sica's Bicycle Thieves, and articles and essays on Holocaust cinema, early film and literature, 'Hollywood on the Tiber', and censorship.

About the Author: Robert S. C. Gordon teaches Italian cinema at Cambridge University. He has published widely on 20th-century Italian literature, cinema and cultural history. He is the author or editor of several books on the work of Primo Levi, including Primo Levi's Ordinary Virtues, Auschwitz Report and The Cambridge Companion to Primo Levi. He is co-editor of Culture, Censorship and the State in 20th-Century Italy and his study of cultural responses to the Holocaust in Italy will appear in 2012. His work on cinema includes Pasolini. Forms of Subjectivity (1996) and Bicycle Thieves (2008), DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries on Pasolini's Teorema and De Sica's Bicycle Thieves, and articles and essays on Holocaust cinema, early film and literature, 'Hollywood on the Tiber', and censorship.

Accattone (1961) was Pier Paolo Pasolini's first film as a director. As Tony Rayns explains in his eloquent and attentive commentary to this new release of the film on DVD and Blu-ray in the Masters of Cinema series (Eureka), Pasolini was already close to 40 when he took to directing. He had helped out here and there with some screenplays and script doctoring for Fellini and Mauro Bolognini, offering his expertise in the street slang and dialect of the poorest underclass of postwar Rome. (Pasolini had lived among them for a time and searched them out for sex for most of his adult life.) More importantly, though, he had an established reputation as a novelist, poet, critic and iconoclastic young literary intellectual in 1950s Rome. This was one of the later and more remarkable conversions to cinema within the pantheon of the great postwar European auteurs. And Accattone, the first fruits of the conversion, is one of the more astonishing screen debuts the medium has ever seen.

Accattone does not set out to tell a smoothly refined arc of a story, but it has a compelling and tragic narrative power.

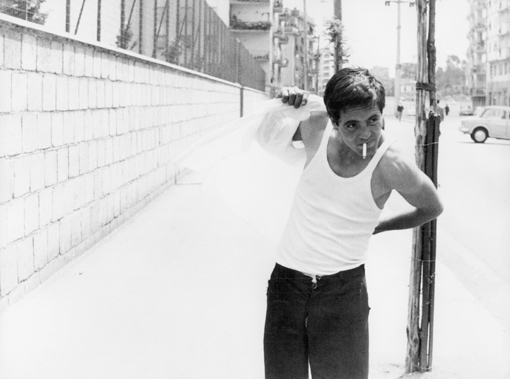

Accattone does not set out to tell a smoothly refined arc of a story, but it has a compelling and tragic narrative power. The hero, Vittorio, nicknamed 'Accattone' or 'scrounger' (Franco Citti), is one of a group of young men lazily spending their days not so much unemployed as beyond the realm of economics as we know it. They hang around bars - Rayns points out that one backstreet bar turns up five times, the boys lolling around its rickety tables in the sunlight every time - and they chat futilely, in broad Roman dialect. Work is anathema for them; at best some of them dabble in petty theft or, like Accattone himself, live off their women, pimping. They are irredeemable, and Pasolini's largely improvised film style and cinematography - more early Renaissance than neo-realist - shows them as flat, ugly, almost grotesque. And yet Pasolini, borrowing from Bach and touches of Dreyer, and sprinklings of homoeroticism, does his best to redeem them, through the same strange, Marxist-atheist strain of spirituality that would propel his great film Gospel According to Matthew (1964) [reviewed by Dr Miles Booy here]. Accattone meets the luminous Stella, and even as he seduces her into prostitution, he intuits something of her purity; even as he disastrously takes up hard labour for a day, mocked by his fellow scroungers, he dreams of and then lives through a death that looks something like a perverse salvation.

It is a strange and disorienting vision, distinctly odd and eccentric as sociology, luminescent as myth and a primal form of cinema. The sunlight of Rome's slum periphery, beating for long tracking shots as Accattone wanders towards his women, his gang, his dreams, his death, carries an almost overwhelming charge. All the more reason to welcome the new high-definition transfer with a corrected aspect ratio. It claims to be the first Blu-ray edition anywhere.

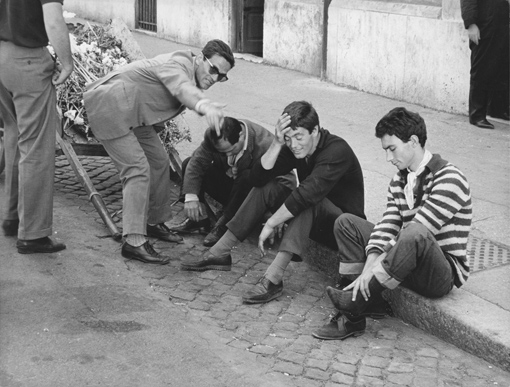

Bundled in with Accattone is an accompanying film that is almost as striking, but much less well known. In 1963, Pasolini made his first documentary, Comizi d'amore or 'Love Gatherings', an enquiry that is part anthropological part psychoanalytical, into the attitudes of early 1960s Italians towards the taboo subject of sex. Pasolini travelled widely, from Sicilian villages to Milanese dance halls to the Bologna FC football team, pushing his microphone at unassuming men, women and children asking 'where babies come from?', 'whether they've heard of homosexuality?', 'whether it's better to be a good lover or a good father?'. In between, a handful of intellectuals - including a leading Freudian and the major novelist of the day (and Pasolini's friend), Alberto Moravia - opine pompously or knowingly on their nation's ignorance and repressions. The portrait that emerges, through heavy doses of embarrassment and awkward dialogue, is a fascinating one of a society fractured and lost in the face of its hyper-accelerated lunge into modernity. Pasolini was one its great contrarian chroniclers.

Robert S. C. Gordon