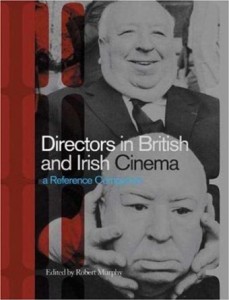

Directors in British and Irish Cinema edited by Robert Murphy (bfi, 2006), 672 pages, ISBN: 1844571262 (Paperback), £29.99, ISBN: 1844571254 (Hardback), £95.00

About the reviewer: A distinguished filmmaker and historian, Kevin Brownlow is also the acclaimed author of several books. These include his prize-winning 1996 biography of David Lean as well as: The Parade's Gone By ... (1968); The War, the West and the Wilderness (1979); Napoleon: Abel Gance's Classic Film (1983); Behind the Mask of Innocence (1990); Winstanley. Warts and All (2009)

I was dreading this directory of directors. Publications from the British Film Institute usually require frequent trips to the dictionary. But Robert Murphy, the editor, deserves our gratitude. He asked contributors to avoid academic jargon. The result is a book of enormous value.

... a book of enormous value

Directing is the hardest job I have ever done, which is why I admire anyone who practises it. (Well, almost anyone.) Yet I am frequently shocked by the brutality of film critics. Every critic should be required to direct at least one film before being allowed to practise their craft. They could then never dismiss films with undisguised contempt. Murphy’s contributors regard their subjects with what I call the ‘Brian McFarlane Approach’: a sympathy born out of a genuine knowledge of the subject (McFarlane is a frequent contributor).

The first film I witnessed being made was The Devil Girl from Mars (1954). As a teenage filmmaker, I had been taken to Shepperton by a newspaper and to my horror they quoted every one of my disparaging remarks in the next morning’s edition. I feel the embarrassment to this day. For the film was directed by David Macdonald, a distinguished veteran who had been Cecil B De Mille’s assistant and the lighting, which looked so dire to me, was by Hitchcock’s cameraman, Jack Cox. Andrew Spicer, in this directory, tells us that the film has now attained cult status.

I was impressed that the directory is packed with names from the silent era, often accompanied by wonderfully quirky details; did you know that A.V. Bramble (director of Shooting Stars, 1927) plays a tribesman in Carol Reed’s Outcast of the Islands (1952)?

Several names in this directory I worked with - I relished McFarlane’s phrase about Lindsay Anderson, ‘he was not a man to change his mind’ (!) - and many more I knew as my career bounced between modern film-making and historical research. I loved Lothar Mendes, a civilised and intelligent man, but I have to admit his films tended to be dull. In Hollywood in the 1960s I watched a TV drama being shot. The director called ‘Cut, pr-r-rint, pairfekt!’ The assistant leaned over and whispered ‘He talks like Lubitsch but he directs like Lothar Mendes.’

Several names in this directory I worked with - I relished McFarlane’s phrase about Lindsay Anderson, ‘he was not a man to change his mind’ (!) - and many more I knew as my career bounced between modern film-making and historical research. I loved Lothar Mendes, a civilised and intelligent man, but I have to admit his films tended to be dull. In Hollywood in the 1960s I watched a TV drama being shot. The director called ‘Cut, pr-r-rint, pairfekt!’ The assistant leaned over and whispered ‘He talks like Lubitsch but he directs like Lothar Mendes.’

Lindsay Anderson, a professional curmudgeon, would be shocked at how little I found to quarrel with in this book. David Lean could not have started as a clapper boy since he joined the industry when it was still silent. William Beaudine’s American silents were a great deal more accomplished than his British talkies. And if one or two of the contributors had been film collectors, like me, and had paid hard cash for, say, a John Argyle film, they would have been less Brian McFarlane in their approach and a lot more ‘Brutal Film Critic’!

Heroes of this book include Geoff Brown, who seems to have written about every obscure director, including me, and Luke McKernan, whose filmography of Lewin Fitzhamon has to be seen to be believed. But we owe everyone connected with this admirable venture a profound debt.

Kevin Brownlow