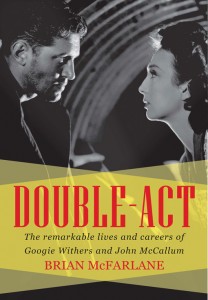

Double-Act: The Remarkable Lives and Careers of Googie Withers and John McCallum by Brian McFarlane (Monash University, May 2015), 288 pages, ISBN: 978-1922235725 (paperback), £31

About the Reviewer: Professor Charles Barr taught for many years at the University of East Anglia, and more recently in the USA and in Dublin. He is currently a Research Fellow at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, and is active on the board of the US-based scholarly journal The Hitchcock Annual. His pioneering work on British cinema includes Ealing Studios (rev. edn, 1999) and English Hitchcock (1999), and, as editor, All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema (1986); and he was researcher and co-writer of Stephen Frears’s film Typically British: A Personal History of British Cinema (1995). The second edition of his book on Vertigo for the BFI Film Classics range was published in 2012. With Alain Kerzoncuf he is the co-author of Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films (2015).

About the Reviewer: Professor Charles Barr taught for many years at the University of East Anglia, and more recently in the USA and in Dublin. He is currently a Research Fellow at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, and is active on the board of the US-based scholarly journal The Hitchcock Annual. His pioneering work on British cinema includes Ealing Studios (rev. edn, 1999) and English Hitchcock (1999), and, as editor, All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema (1986); and he was researcher and co-writer of Stephen Frears’s film Typically British: A Personal History of British Cinema (1995). The second edition of his book on Vertigo for the BFI Film Classics range was published in 2012. With Alain Kerzoncuf he is the co-author of Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films (2015).

This new book has a hyphen, Double-Act, thus distinguishing it from the unhyphenated Double Act, written by the actor Michael Denison (London: Michael Joseph, 1985). That was a record of his long partnership, on stage and on screen and in marriage, with Dulcie Gray. Denison and Gray had much in common with the subjects of Double-Act, John McCallum and Googie Withers. Each couple came together during the great decade of British Cinema: as co-stars of, respectively, My Brother Jonathan (1948) and of the successive Ealing melodramas The Loves of Joanna Godden and It Always Rains on Sunday (both 1947). Each couple made a few more films together, but the stage partnerships went on much longer, as did the six-decade marriages: the men died first, the widows both living on to 2011, having reached 95 (Dulcie Gray) and 94 (Googie Withers).

It’s mildly surprising that Brian McFarlane doesn’t, in his own new joint biography, mention the Denison book, given its title. No-one is as knowledgeable as he is on the history and literature of British cinema. His great interview book Sixty Voices (London: BFI, 1992) includes joint interviews with these two couples, alongside a mass of solo ones. And the new book records two moments when the couples’ paths crossed very cordially: as hosts and guests in London, and on a theatre tour. But the unhyphenated Double Act is long out of print, and long forgotten, as, to be blunt, are the careers of Gray and Denison, except among specialists. Withers and McCallum and their works are more memorable and more significant, and Double-Act, with its hyphen, should still be a reference point thirty years from now.

It’s mildly surprising that Brian McFarlane doesn’t, in his own new joint biography, mention the Denison book, given its title. No-one is as knowledgeable as he is on the history and literature of British cinema. His great interview book Sixty Voices (London: BFI, 1992) includes joint interviews with these two couples, alongside a mass of solo ones. And the new book records two moments when the couples’ paths crossed very cordially: as hosts and guests in London, and on a theatre tour. But the unhyphenated Double Act is long out of print, and long forgotten, as, to be blunt, are the careers of Gray and Denison, except among specialists. Withers and McCallum and their works are more memorable and more significant, and Double-Act, with its hyphen, should still be a reference point thirty years from now.

And yet: some people, even specialists, today look blank when one mentions the name of Googie Withers (the book reminds us that the first syllable is pronounced as in wood, not boom). Such people need urgently to to get out more, to see the films, and to read the book. These days, so much is accessible that it is hard to make choices, to see the wood for the trees. But really there is no excuse for not knowing and honouring her wonderfully strong and sexy roles in 1940s British Cinema, notably It Always Rains on Sunday, opposite her soon-to-be husband – though her equally ground-breaking role as a doctor in White Corridors (1950) is still, sadly, harder to access. Like many film stars of the 40s, Michael Denison went on to a weekly TV role as Boyd Q.C.; far more memorable was Googie Withers as the prison governor in the Granada series Within These Walls, a superb examplar of how to temper justice with mercy.

But the extra dimension to the twin careers of Double-Act, compared with Gray-Denison and other British partnerships, is the international one, to which Brian McFarlane, as an anglophile Australian, does full justice. McCallum had come from Australia to England in the 1940s to seek his cinematic fortune, and eventually, after marriage, took Withers back with him, first seasonally, and then permanently. McFarlane chronicles in fascinating detail the role of the couple, and of their growing family, as ‘Australian royalty’. And he reminds us of the serious role that McCallum had, alongside his continuing Anglo-Australia stage career, in the growth of the Australian film and television industries: as promoter of Michael Powell’s pioneer film They’re a Weird Mob (1966), and of the kangaroo TV series Skippy (from 1967).

The book’s cover describes it as ‘not just a fine joint biography, but an important work of cultural history.’ We are familiar enough with the story of the Australians who came to Britain in the 60s: Germaine Greer, Clive James, Barry Humphries. The story of Withers and McCallum supplies an indispensable complement. All university libraries should have it.

Professor Charles Barr