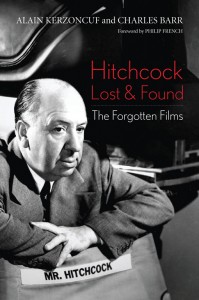

Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films by Alain Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr (University of Kentucky Press, February 2015), 268 pages, ISBN: 978-0813160825 (hardback), £40

About the reviewer: Sue Vice is Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield. Having completed an MA in Film Studies at Sheffield Hallam, she now teaches a course on the films of Alfred Hitchcock, as well as teaching on the representations of the Holocaust in literature and film. Her published works include Children Writing the Holocaust (Palgrave, 2004), Introducing Bakhtin (Manchester University press, 1997), Holocaust Fiction (Routledge, 2000) and Jack Rosenthal (Manchester University Press, 2009). She is currently working on a new project focusing on the novelist and screenwriter Barry Hines.

About the reviewer: Sue Vice is Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield. Having completed an MA in Film Studies at Sheffield Hallam, she now teaches a course on the films of Alfred Hitchcock, as well as teaching on the representations of the Holocaust in literature and film. Her published works include Children Writing the Holocaust (Palgrave, 2004), Introducing Bakhtin (Manchester University press, 1997), Holocaust Fiction (Routledge, 2000) and Jack Rosenthal (Manchester University Press, 2009). She is currently working on a new project focusing on the novelist and screenwriter Barry Hines.

Alain Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr are both well-known for their scholarship on aspects of Alfred Hitchcock’s films. In this fascinating and absorbing book, their analysis ranges over almost all of his long career, while paying particular attention to those ‘transitional moments’ from which the lost, overlooked and forgotten material tends to emerge.

Kerzoncuf and Barr preface their analysis with Paula Marantz Cohen’s insight that to study Hitchcock is ‘to study the entire history of cinema’, and Hitchcock Lost and Found bears this out, with its inclusion of the director’s silent as well as Hollywood work, public-service and war-time releases. The authors explore the varied significance of what ‘lost’ actually means: the term encompasses films that no longer exist or do so only partially, of which a revised or alternative version is missing, which are lost to sight or neglected, or which have been withheld from public view. The authors acknowledge that Hitchcock’s involvement in retrieved works is not always quite what it seems, for instance in relation to The White Shadow of 1924, a ‘lost Hitchcock film’ which was discovered in New Zealand in 2011. The lost work was in fact an incomplete print of a film directed by Graham Cutts, one of Hitchcock’s earliest mentors and for whom he acted as ‘all-purpose lieutenant’.

The authors’ detective-work, in tracking down the precise detail of Hitchcock’s role in each of the retrieved films, is matched by detailed and persuasive textual readings. These take the form of tracing links between the recovered material and Hitchcock’s later work, for instance the ‘brutal intensity’ of a shot-reverse-shot structure signifying marital violence in the early Flames of Passion (1922) just as it does in Marnie (1964). Since the former was also directed by Cutts, Kerzoncuf and Barr argue for a concept of ‘affinity’ as much as influence between Hitchcock and his mentors, revealing him to be akin to a ‘sponge’ in absorbing multiple styles, not least that of documentary, as attested by the homage Hitchcock on Grierson, broadcast on Scottish television in 1969.

The book’s illustrations are wonderfully chosen, in the form either of the authors’ findings from trade papers and archives, or stills from the lost films, for instance those comparing the original English-language release of Murder! with its lost German version, Mary (1930). Lists and tables are used helpfully to convey an overview of, for instance, the edits to the voiceover and shots made by Hitchcock for the American version of the British propaganda film Men of the Lightship (1940), and to summarize significant advances in the authors’ argument. The book concludes with an engaging ‘top ten’ wishlist on Kerzoncuf and Barr’s part of lost material they would most like to come to light, including three films directed by Hitchcock, most notably his second feature Mountain Eagle of 1926. It might also have been useful to have attempted a synoptic concluding chart of the films in which Hitchcock was involved, summing up his role particularly in the early films, about which a narrative summary can become confusing.

Kerzoncuf and Barr note that between the writing and publication of their book new discoveries will inevitably have been made, and indeed there is now even more to be said about Hitchcock’s involvement in Sidney Bernstein’s shelved film of the liberation of Belsen and other Nazi camps, in light of André Singer’s Night Will Fall (2014) tracing its history. Laura Mulvey’s classic article on the male gaze is invoked, but it would have been interesting to read about the authors’ view of her recent claim that Hitchcock’s representations were more self-consciously ironic than she had previously argued. In some cases the book reproduces the text of ‘lost’ material, such as Hitchcock’s remarkable filmed address to the Westcliff Cine Club of 1963, an encomium to the ‘dreariness’ of his native Essex, although the long quotation ends abruptly without the authors’ commentary.

But these are minor quibbles, and overall this book will be of great benefit not only to Hitchcock scholars and teachers, by revealing in such detail the origins of the director’s distinctive practice, but to those interested in film archives and history as well as the national cinemas of Britain and the USA from the earliest days of the 1920s up to the 1970s: that is, cinema’s and Hitchcock’s crucial half-century.

Professor Sue Vice