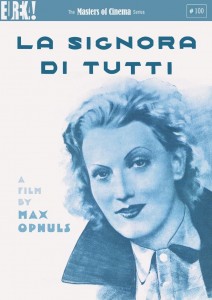

La signora di tutti [Everybody’s Lady] 2010. UK. DVD. 86 minutes. Eureka Entertainment.£19.99

About the reviewer: Danielle Hipkins is Senior Lecturer in Italian at the University of Exeter. She has published on postwar Italian women’s writing, cinema and gender, and is currently working on Italy’s Other Women: Gender and Prostitution in Postwar Italian Cinema, 1942-1965 (forthcoming). She is Co-investigator on the Italian Cinema Audiences project Her research into Italian audiences of the 1940s and 1950s comes out of this project, and she is particularly interested to understand more about how gender identity has affected cinema-going choices and reception, as well as memories of this period. Previous publicaions include Contemporary Italian Women Writers and Traces of the Fantastic: the creation of literary space (2007); 'Italian Cinema from the Perspective of Female Friendship' in The Italian Cinema Book (2014); 'Lost Girls: Daughters of sin in Italian melodrama' in Hipkins DE, Pitt R (eds) New Visions of the Child in Italian Cinema (2014).

About the reviewer: Danielle Hipkins is Senior Lecturer in Italian at the University of Exeter. She has published on postwar Italian women’s writing, cinema and gender, and is currently working on Italy’s Other Women: Gender and Prostitution in Postwar Italian Cinema, 1942-1965 (forthcoming). She is Co-investigator on the Italian Cinema Audiences project Her research into Italian audiences of the 1940s and 1950s comes out of this project, and she is particularly interested to understand more about how gender identity has affected cinema-going choices and reception, as well as memories of this period. Previous publicaions include Contemporary Italian Women Writers and Traces of the Fantastic: the creation of literary space (2007); 'Italian Cinema from the Perspective of Female Friendship' in The Italian Cinema Book (2014); 'Lost Girls: Daughters of sin in Italian melodrama' in Hipkins DE, Pitt R (eds) New Visions of the Child in Italian Cinema (2014).

The excellent transfer of Max Ophuls’ second film brings its meditation on the labyrinth of female beauty and media celebrity to 21st century UK audiences with a vibrancy and innovative force that makes its original release date in Italy of 1934 seem less distant. Isa Miranda is the unlucky blonde heroine cursed with a preternatural power to attract the opposite sex, who first gets thrown out of school before capturing the attention of her young lover’s father. It is only after she has caused several violent deaths, and lost her first lover to her sister, that she realizes she is doomed to a life of lonely stardom and attempts suicide. The story is, as so many good melodramas are, narrated in flashback from under a sinister anaesthetic as doctors try to bring her round, underlining that it is the how and not the whether of Gaby’s disastrous trajectory that interests us.

The film is accompanied by a half hour documentary by film historian, Tag Gallagher, who has a particular interest in the Italian context and Max Ophuls. So Alone, as the feature is called, offers some thought-provoking reflections on the film, in particular on the interpretation of Gaby herself as more than a passive victim, and on the quirks of Ophuls’ unique style. It also offers an alternative to the usual, and distracting, voice-over commentary to accompany the film, through a series of repeat clips from the film which serve as a useful reminder that the richness of Ophuls’ film requires our attention again - and again. For students it provides a shortcut, and far more effective route into understanding Ophuls’ style than any amount of text. At the same time it sets the film in the context of Ophuls’ other work, showing us rather then simply telling us how it fits into Ophuls’ artistic oeuvre.

The film is accompanied by a half hour documentary by film historian, Tag Gallagher, who has a particular interest in the Italian context and Max Ophuls. So Alone, as the feature is called, offers some thought-provoking reflections on the film, in particular on the interpretation of Gaby herself as more than a passive victim, and on the quirks of Ophuls’ unique style. It also offers an alternative to the usual, and distracting, voice-over commentary to accompany the film, through a series of repeat clips from the film which serve as a useful reminder that the richness of Ophuls’ film requires our attention again - and again. For students it provides a shortcut, and far more effective route into understanding Ophuls’ style than any amount of text. At the same time it sets the film in the context of Ophuls’ other work, showing us rather then simply telling us how it fits into Ophuls’ artistic oeuvre.

It is the emphasis on the auteur-based approach favoured by such a series that can sometimes run the risk of implying that such works are the isolated blooms of pure genius. It is inevitable, perhaps, that Ophuls’ status as exilic, and nomadic director (as Jew he fled Germany to work on films in Italy, France, and the US) should reinforce this tendency. However, much of his team was very much rooted in the Italian context, and as such the film has an Italian flavour which might merit greater acknowledgement in the accompanying material. In an otherwise helpful essay by Luc Moullet, which only occasionally rings off key due to its translation, and sets the film in a broader transnational context, the author claims that the flashback technique was unheard of in its time. In fact, Amleto Palermi’s silent film of 1928, Le confessioni di una donna, uses a similar hospital bed structure to unpick the life of a woman gone astray, albeit in far less sophisticated a fashion. The accompanying booklet also contains a series of interviews and testimonials of those involved in making the film, which provide titillating background information, in particular as to the working relationship between Ophuls and his female lead, whom he apparently pricked with pins to provoke looks of sufficient suffering. In conclusion the consideration of the gender dynamic is perhaps a direction in which reflective material on the film could have been pushed further. Gallagher suggests that Gaby is no passive victim, but for understanding the context of representations of femininity in the period, in which madness, stardom and sexuality collide, interested viewers might look to the work of feminist critics such as Marcia Landy or Mary Ann Doane.

Danielle Hipkins