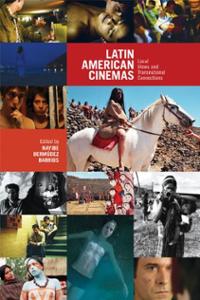

Latin American Cinemas: Local Views and Transnational Connections edited by Nayibe Bermúdez Barrios (University of Calgary Press, 2011). 344 pages. ISBN: 978-1552385142 (paperback). £29.50

About the Reviewer: Dr Deborah Shaw, is Reader & Course Leader on the MA Film and TV Studies at the University of Portsmouth. Her principal areas of research are Latin American women’s writing, contemporary Latin American film and representations of Latinos and Latin Americans in Hollywood film. More recently her focus has been on the latter two subject areas, and she is currently working on a monograph on contemporary Mexican filmmakers. Her publications include: The Three Amigos: The Transnational Films of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (Manchester University, 2013); Contemporary Cinema of Latin America: Ten Key Films (2003, Continuum Publishers); and as editor, Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Breaking into the Global Market (2007, Rowman and Littlefield).

About the Reviewer: Dr Deborah Shaw, is Reader & Course Leader on the MA Film and TV Studies at the University of Portsmouth. Her principal areas of research are Latin American women’s writing, contemporary Latin American film and representations of Latinos and Latin Americans in Hollywood film. More recently her focus has been on the latter two subject areas, and she is currently working on a monograph on contemporary Mexican filmmakers. Her publications include: The Three Amigos: The Transnational Films of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (Manchester University, 2013); Contemporary Cinema of Latin America: Ten Key Films (2003, Continuum Publishers); and as editor, Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Breaking into the Global Market (2007, Rowman and Littlefield).

The challenge for any edited book is to ensure coherence while guaranteeing the quality of individual pieces. Latin American cinemas: Local Views and Transnational Connections, does, in the main, achieve this through its emphasis on ‘social and cultural concerns’, and films and critical approaches that deal with ‘identity politics, sexuality, the body, the family, and/or the community’ (1). In the introduction Nayibe Bermúdez Barrios lays out her theoretical frameworks: Jean-Luc Nancy’s notion of ‘inoperative community’; Enrique Dussel’s critique of modernity, seen to be universalist, racist and patriarchal, and Aníbal Quijano’s emphasis on corporality. Thought these frameworks the editor highlights the book’s emphasis on examples of resistance to homogenizing conceptualizations of the nation, on the importance of locating a politics of solidarity, on filmic instances of singularity and on texts that centre peripheral and marginal groups. Finally, many of the chapters read the body as the privileged site for struggle. It should be added that each contributor adopts her/his own framework (only 3 chapters are written by male authors), and many do not reference these theorists.

Bermúdez Barrios organizes the book into three sections. The essays in the first of these ‘Crisis of the Nation state and desire for community’ are connected by readings that highlight the breakdown of unified notions of the nation state and conventional family units and its institutions. Authors also explore the diverse meaning ascribed to the body (as sites of power and violence, and victimization in the case of Garcés and Osorio study on Lombardi’s Peru), or sites of desire and transgression (in the case of Paola Arboleda Río’s analysis of two films by Lucrecia Martel). The essays explore different approaches taken by filmmakers towards the allegorical. Some readings demonstrate how films narrate the nation; this is the case with Rebecca Lee ‘s chapter on Campanella's Argentina in Luna de Avellaneda, and Garcés and Osorio’s reading of Ojos que no ven; while in Martel’s case, Arboleda Río convincingly argues that the allegorical is rejected. David W. Foster’s chapter, ‘Films by Day and Films by Night in São Paulo’, while solid as a stand alone piece, does seem slightly at odds with the other chapters in its focus on the representation of the city in four film texts from the 1960s to the 2000s.

Bermúdez Barrios organizes the book into three sections. The essays in the first of these ‘Crisis of the Nation state and desire for community’ are connected by readings that highlight the breakdown of unified notions of the nation state and conventional family units and its institutions. Authors also explore the diverse meaning ascribed to the body (as sites of power and violence, and victimization in the case of Garcés and Osorio study on Lombardi’s Peru), or sites of desire and transgression (in the case of Paola Arboleda Río’s analysis of two films by Lucrecia Martel). The essays explore different approaches taken by filmmakers towards the allegorical. Some readings demonstrate how films narrate the nation; this is the case with Rebecca Lee ‘s chapter on Campanella's Argentina in Luna de Avellaneda, and Garcés and Osorio’s reading of Ojos que no ven; while in Martel’s case, Arboleda Río convincingly argues that the allegorical is rejected. David W. Foster’s chapter, ‘Films by Day and Films by Night in São Paulo’, while solid as a stand alone piece, does seem slightly at odds with the other chapters in its focus on the representation of the city in four film texts from the 1960s to the 2000s.

Writing about section two, ‘Sexuality, Rape and Representation’, Bermúdez Barrios highlights the essays’ connections: these are seen in their focus on representations of singularity, which are for the editor a liberating force to counter homogenizing forms of representation that are bound up with patriarchy and nationalism. Singularity is highlighted through the authors’ focus on gender and sexuality. Thus, Gerard Dapena reads the queer filmmaking of Julián Hernández productively through Deleuze’s theories of affect and the body; Charlotte E. Gleghorn considers the narrative strategies of otherness adopted in in Lucía Puenzo's extraordinary film XXY, that tells the story of Alex who is intersex and refuses accepted medical practices and confinements of gender and sexuality. In the final essay of the section Isabel Arredondo links rape to socio-political structures through her reading of two films by Mexican filmmakers María Novaro and Marisa Sistach.

The third part ‘Visions of the Transnational’, also highlights singularity in its focus on the opening up of spaces for counter cinemas and emergent cinemas, and new forms of representations for marginalized groups privileged in these forms. This section adds to the field of Latin American film studies in its consideration of lesser known film cultures. There is also more emphasis here on production, exhibition and distribution contexts, which were rather lacking from previous sections. Keith John Richards has a fascinating and rich chapter on Juan Mora Catlett's Eréndira Ikikunari in which he applies Enrique Dussel’s ideas of liberation philosophy and transmodernity and Raúl Ruiz’s ideas of shamanic cinema to the film, and demonstrates liberating ways of reconfiguring historical indigenous Mexican identities through film. Elissa J. Rashkin, known for her work on women’s filmmaking in Mexico, explores women and video in Zapatista Chiapas, and the possibilities for indigenous female forms of self-representation through independent videos. The author outlines an important but under-researched element in the story of Mexican film and highlights both the impact and production difficulties for these non-commercial cultural texts.

Nayibe Bermúdez Barrios’ essay ‘Sexploitation, Space, and Lesbian Representation in Armando Bo's Fuego’ explores non-mainstream, global forms of stylizing the female body, and considers the transnational spaces for the lesbian subject in sexploitation films. In short, the author argues that sexploitation films are a transnational form of counter cinema. Finally, Juana Suárez addresses another under-researched area, and interrogates Colombian cinema’s search for a film industry, and formulates it as an example of minor transnationalism, using the concept from Francoise Lionnet and Shu Mei Shih. In the chapter, Suárez argues that Colombian filmmaking is at a crossroads, and she explores this by placing Colombian filmmakers within the context of Latin American transnational cinema, and then considering the national arena and the role of a cinema law in the promotion of a sustainable industry.

... a valuable contribution to the growing field of Latin American film scholarship

Latin American cinemas: Local Views and Transnational Connections is a valuable contribution to the growing field of Latin American film scholarship. The reader can enjoy these essays confident of the expertise of the authors, who give an insight in the social context, and, in the main, apply theoretical readings judiciously to their case studies, although with some exceptions, there is little engagement with transnational film theory. The focus in the final section ‘Visions of the Transnational’ on lesser known forms of filmmaking is interesting and brings a new perspective to the field, although, the most obvious examples of commercial Latin American transnational filmmaking is neglected. This is not a problem in itself as this book fills a critical gap, however, this is not something the reader may expect from the book’s title.

Deborah Shaw