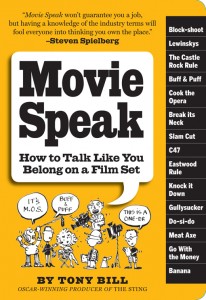

Movie Speak: How to Talk Like You Belong on a Film Set by Tony Bill (Workman Publishing, June 2009), 216 pages, ISBN: 978-0-7611-4359-8 (paperback), £6.99

About the Reviewer: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It – The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). He is currently writing Armchair Cinema: Feature Films on British Television for publication in 2016.

About the Reviewer: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It – The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). He is currently writing Armchair Cinema: Feature Films on British Television for publication in 2016.

While we may occasionally like to pretend otherwise, most academics have no real idea of what goes on on a movie set. Even less do we have much experience of the professional slang used by filmmakers, which could not be further from the equally specialised jargon of Film Studies. Once, while enjoying the rare privilege of a set visit, I was asked by the unit sound recordist if I taught ‘semiotics’. The dripping contempt with which he uttered the dread word let me know at once that I would be persona non grata if I admitted guilt (fortunately, I could honestly say that semiology was not my bag either).

Though it is hardly aimed at a scholarly readership, Tony Bill’s useful and amusing little book Movie Speak will nevertheless serve as a handy guide to industry argot and professional politics. It should also help save the embarrassment of any misguided novice tempted to compliment the director on his mise-en-scéne. Bill’s advice here is succinct: ‘Never use this term on a film set; it will mark you out as an academic or a total dweeb. Plus, no one will know what you’re talking about anyway’.

Bill clearly does know what he’s talking about. He is himself the director and/or producer of a number of Hollywood movies marked by their consistent intelligence and individuality; they include Hearts of the West, My Bodyguard, Six Weeks, Five Corners, Untamed Heart and the Oscar-winning The Sting (which he co-produced). As a young actor, he appeared in such films as Come Blow Your Horn (his first, opposite Frank Sinatra, in 1963), Ice Station Zebra and Shampoo. With a career spanning more than 45 years and a gift for the common touch in writing, he is well qualified to pass on his insider knowledge, which extends far beyond the alphabetical glossary of colloquial terms and phrases itemised in the bulk of the book.

Bill clearly does know what he’s talking about. He is himself the director and/or producer of a number of Hollywood movies marked by their consistent intelligence and individuality; they include Hearts of the West, My Bodyguard, Six Weeks, Five Corners, Untamed Heart and the Oscar-winning The Sting (which he co-produced). As a young actor, he appeared in such films as Come Blow Your Horn (his first, opposite Frank Sinatra, in 1963), Ice Station Zebra and Shampoo. With a career spanning more than 45 years and a gift for the common touch in writing, he is well qualified to pass on his insider knowledge, which extends far beyond the alphabetical glossary of colloquial terms and phrases itemised in the bulk of the book.

These range from ADR (Automated Dialogue Replacement, or ‘looping’) to ‘the zone’ (‘The area near the particular city in which the (union) crew lives’), and in between encompass, for example, the specific connotations of the various producer credits, the meaning and origin of nicknames for different types of lighting unit and other set equipment, short guides to professional techniques and practices, the instructions and expressions most likely to be overheard from crew members (shouted or muttered, as befits the occasion), and the sage aphorisms accepted in the industry as philosophical truth.

In addition to the short entries, Bill comes into his own with half a dozen longer pieces in which he confides some of the secrets of getting on in the business. Though he scorns how-to guides to screenwriting, he offers his own ‘dirty dozen’ of things not to do in writing and submitting scripts, a list which has apparently entered Hollywood lore. Bill also passes on advice for directing actors and on the importance of preserving that least likely showbiz commodity, courtesy (or ‘setiquette’). One can somehow tell from his films that Bill is a nice bloke; this book confirms it.

Dr Sheldon Hall