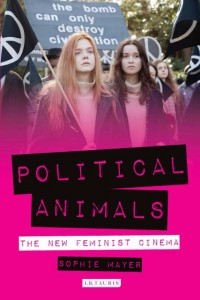

Political Animals: New Feminist Cinema by Sophie Mayer, (I.B. Tauris, 2016), 260 pages, ISBN: 978-1784533724 (paperback), £16.99.

About the reviewer: Dr Janet McCabe, Senior Lecturer in Film and Television at Birkbeck, University of London, is principally interested with contemporary television, gender politics and feminism, cultural memory and representations of the historical imagination in the media. She is the managing editor of the TV journal Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of TV Studies and has contributed to such publications as Aesthetics and Style (Continuum, 2013), The Essential Sopranos Reader (University Press of Kentucky, 2011) and It’s Not TV: Watching HBO in the Post-Television Era (Routledge, 2008).

Over 40 years ago, at the Edinburgh Film Festival, Laura Mulvey, Claire Johnston and Lynda Myles co-programmed a week event that included every film made by a woman available to them. In 1972 the group anticipated that by the turn of the new century 50 per cent of films would have a woman at the directing helm. It's now 2016 and the predication has failed to materialise. Structural absence and systematic exclusion from the dominant modes of film production continues to define the role of women in the industry, which, in turn, make books like Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema by Sophie Mayer so essential. Not only does the book offer a timely political aerial view of a new generation of feminist filmmakers, but it also draws attention to women’s creative skills and political imagination, of the particular ideas with which they work and how they politicise them in the process.

Political Animals animates the social, cultural and political arguments for contemporary feminist advocacy, representation and visibility. Redefining what a twenty-first century feminist cinema looks and ‘feels’ like, the book consists of 10 chapters. Chapter one reviews the current state of affairs, where the facts and figures produced by bodies like the European Women’s Audiovisual Network (EWA) reveal ‘the persistence of systemic inequality’ (p.14). Mayer, however, seeks to provide an alternative perspective on how to appreciate contemporary feminist cinema. Looking beyond the commercial mainstream, with its definitions of financial success, she argues that to gain ‘a full picture of feminist cinema, we need to go outside the conventional narratives of film history and reportage’ (ibid).

What follows in the subsequent chapters is an attempt to move the debate beyond Hollywood and politically engage instead with questions of representation and representational justice in a contemporary feminist cinema from anywhere and everywhere else. Chapter 3, for example, deals with ecologically engaged films as a way of thinking differently about a feminist filmmaking practice. The ‘feminist aesthetics of water’ (p.46) is not only about form and narrative, but also the politics of resources and ‘representational justice’ in how these films ‘open up their protagonists and audiences to depths of emotion and a breadth of politics (p.62). Using the ‘frame of war’, chapter 4 builds on representational concerns of justice and gendered violence, to argue of how war is lived in female bodies. Displaced protagonists, transcending borders: chapter 5 focuses on trauma and runaways of contemporary British feminist cinema, while chapter 6 loosens the corsets of costume dramas to rethink how we can reclaim and re-imagine a feminist past and its historical protagonists differently.

Feminist tales that challenge heteronormative values and trouble any easy definition of desire and fantasy, to reveal ‘just how productive the “scandalous” territory of the feminist film unconscious could be’ (p.22), are explored in chapters 7, 8 and 9. Chapter after chapter offers the textual evidence, where women filmmakers embed politics deep into the very fabric of the mise en scene and practices of storytelling. The steer dazzling number of contemporary twenty-first century films analyzed, nearly 500 movies by filmmakers ‘who identify as female, trans, intersex, non-binary and/or Two-Spirit (among other non-EuroWestern gender identities), from 60 countries’ (p.2), is testimony to the scope of the ambition, concluding with the epiphany that ‘feminist films is an ‘open letter’ (p.190).

This exhaustive survey of contemporary feminist filmmaking leads to Mayer’s own ‘open letter’, and where, for me at least, the pulsating and exuberant heart of this remarkable book truly lies. Given Mayer’s own identity as an academic, film journalist and feminist film activist with curators of Club des Femmes and campaigner, her ‘open letter’ (rather than conclusion) resonates as a call to political arms. It is not enough, for example, to recognise feminist cinema as a mode of practice, but to intervene through film criticism and curatorial practice, advocating to translate filmmaking opportunities for women into distribution, exhibition, audiences and posterity. What the book highlights is the importance of feminist voices in collectively supporting feminist work. If feminist films are to make a difference and hold out the possibility of changing the heteronormative script, these films must enter into our collective imagination to change us—to affect change and initiate conversation. Political Animals is thus itself a political act, turning research into activism and speaking fiercely to the urgency of now.

Dr Janet McCabe