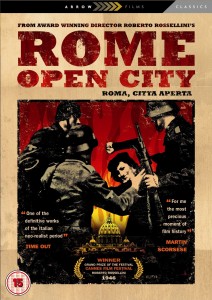

Rome, Open City (Roma, città aperta ). GB. DVD. Arow Films. 103 minutes. £8

About the reviewer: Ron Guariento is a retired film and television producer and a lecturer at Newcastle University. Ron worked in Granada TV drama and documentary, and in BBC Arts Features. Later he took this experience from the practical to the theoretical to teach film and music studies at Newcastle University.

Sixty years after the Second War we recycle our TV images of Victory-in-Europe’s familiar cheering crowds. Rossellini’s 1945 Rome, Open City (1945) – now restored and reissued on a fine DVD - reminds us of another, pervading mood of that time. As with the war, Rossellini’s film is a tragedy; and a sense of melancholy hangs over that film, which has continued like a pedal note throughout a realist cinema it inspired.

Sixty years after the Second War we recycle our TV images of Victory-in-Europe’s familiar cheering crowds. Rossellini’s 1945 Rome, Open City (1945) – now restored and reissued on a fine DVD - reminds us of another, pervading mood of that time. As with the war, Rossellini’s film is a tragedy; and a sense of melancholy hangs over that film, which has continued like a pedal note throughout a realist cinema it inspired.

The 1930s lead-up to war and the War itself gave cinema a national authority. Within the limits of prevailing censorships the War provided a key moment for filmmakers in the Democracies and the Fascist countries. In both, though for different reasons, a representation of ordinary working people was finally allowed serious screen time. The broad aim of liberals was at least a new realism, with the hopeful intent to alter issues of class. These two objectives could be served by a combined realism and melodrama. Rome, Open City was not the first feature Documentary/Drama. Serious attempts to portray real people in real locations were a feature of several wartime and post-war films on both sides of the Atlantic, including Launder and Gilliat’s Millions Like Us (1942), Visconti’s Obsession (Ossessione) (1942) and producer Louis de Rochemont’s House on 92nd Street (1945).

Rossellini’s film shared their agenda but its purpose was less benign. Rome - Open City exposed a desperation among Italy’s Left to atone for their country’s twenty-three-year embrace of Fascism. This film was passionate emotionally furious.

Since then, what of its influence? Rossellini’s realist descendants extend to the present: Elia Kazan, Ermanno Olmi, Jules Dassin, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Gillo Pontecorvo, John Frankenheimer, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Francesco Rosi, Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, the Taviani brothers Paolo and Vittorio, Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, Ricky Tognazzi, Gianni Amelio.

Unexpectedly, neorealism informed Italy’s 1960s satirical comedies of manners - Divorce Italian Style (1961), the Bread and Love series (1953-58), Cops and Robbers / Police and Thieves (1951) - and continues to influence the more recent comedies of Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso, 1988), Michael Radford (Il Postino, 1994) Gabriele Salvatores (Mediterraneo, 1991). These elegant studies, underplayed and in a realist mode, offer us an Italy that we wish for - a land of gentle-hearted ordinary people, feckless, passionate ... they are also melancholic films marked by a graceful sense of irony and with shrewd observation of the middle and lower classes.

Ron Guariento