by Rowland Wymer

Sebastiane has a special place in the history of British cinema as a commercially distributed feature-length film which was funded entirely from private sources (‘crowd funded’ would be the term used today), as a film made in Latin (with English subtitles), and as a film which included numerous explicit images of male same-sex desire. It caused a sensation when first screened at the Gate Cinema in Notting Hill in 1976 and generated major public controversy when shown on television by Channel 4 in 1985. It was the first feature film directed by Derek Jarman and the only one where he had to share the directorial credit, having felt the need to ask the experienced BBC film maker Paul Humfress to help him with some of the directing and editing. However, before we reach the co-credit for direction, we are told that we are watching ‘Derek Jarman’s Film’ and there is no doubt as to whose creative vision the film represents. Sebastiane is as important as any of the other ten feature films made by Jarman when it comes to evaluating his overall cinematic achievement.

This idiosyncratic revisioning of the legend of the early Christian martyr, St Sebastian, who was shot to death with arrows in about 300 AD during the reign of the Emperor Diocletian, is an essential purchase for anyone interested in British cinema, Derek Jarman, queer cinema, or the psychology and iconography of martyrdom, and who does not already have the 2001 Second Sight DVD. If one does have this, what are the incentives, apart from a slightly sharper picture, which would induce one to purchase this Blu-ray edition?

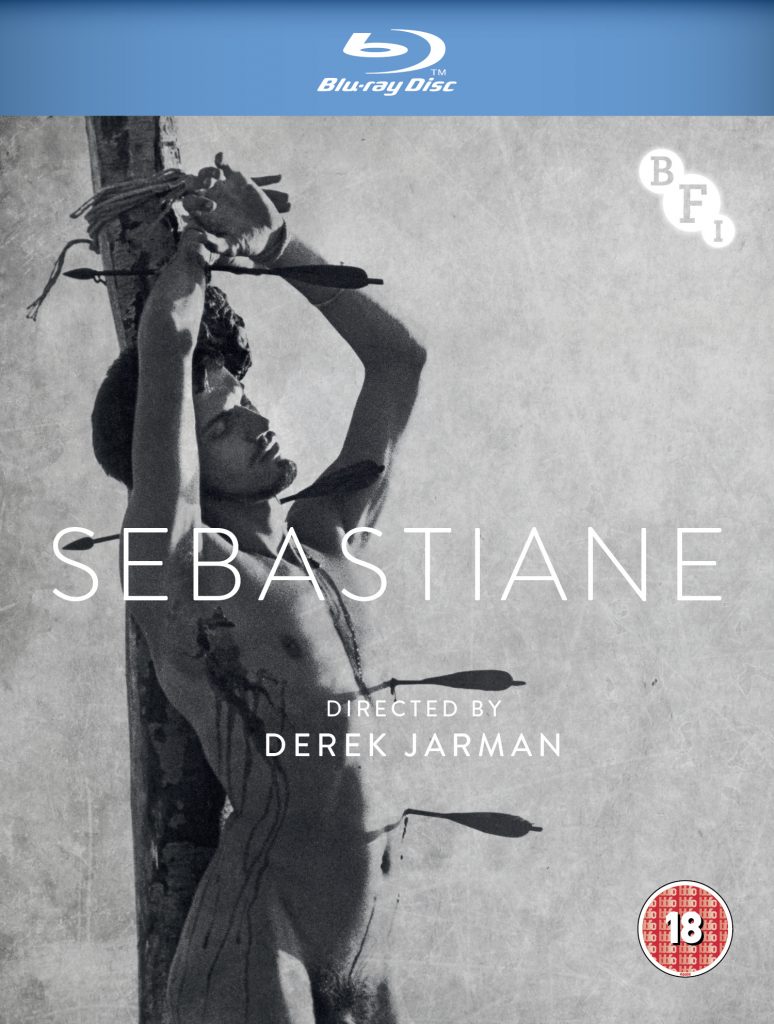

Sebastiane blu-ray cover

The Second Sight DVD included as an extra the important Face to Face interview with Jeremy Isaacs which Jarman gave in 1993, less than a year before his death. The BFI Blu-ray does not have this but includes 128 minutes of other extras. The potentially most interesting-sounding of these is ‘Sebastiane: A Work in Progress’ (62 minutes), which is an ‘alternate edit’ of most of the film (the last part is missing) made at some point in the production process. However, there are not many significant differences observable (partly because the small amount of footage shot had limited the editing choices available) and the experience of watching a fuzzy black-and-white print with an incomplete soundtrack and no subtitles removes much of the mesmerising impact which the final film achieved. One can argue that the distancing effect of this version allows the viewer to look at particular framings more analytically and objectively but I don’t think there are major critical advantages to be gained from viewing this ‘previously unseen’ version.

More immediately pleasurable is ‘The Making of Sebastiane’ (23 minutes), which consists of Super-8 colour footage shot by Jarman and the sound assistant Hugh Smith during the six weeks the actors and crew were on location in Sardinia. The sun, sea, sand, primitive living conditions and bronzed male bodies of the film itself are recreated in a more fun-filled and less intense atmosphere. The powerful evocation of an all-male community is made a little less like a barracks or boarding school by including a couple of glimpses of Luciana Martinez, who seems to be the only woman on the shoot. The many years which have passed since the footage was taken give a characteristic home-movie poignancy to these shots of beautiful young people before time, sickness, and death have done their damage.

Before he made any films, Jarman had had considerable success as a theatrical set designer and was responsible both for the sets and the costumes used by the Royal Ballet in their 1968 production of Frederick Ashton’s Jazz Calendar. Another Blu-ray extra consists of 36 minutes of the Royal Ballet rehearsing this piece. For those of us who have never seen this ballet performed, it is good to get a sense of how it worked on stage but the footage is in black and white and the full impact of Jarman’s sets and costumes can be better appreciated from the excellent colour photographs which can be found in some of the books on Jarman.

Still from Sebastiane (Jarman)

There is also a short interview with the artist and film maker John Scarlett-Davis about his role as an extra in the film’s prologue scene, set in Diocletian’s court and filmed in Andrew Logan’s studio. The supplementary visual material is completed by a Gallery of nine still images, including a couple of pages from the shooting script in which Sebastian is interestingly referred to as Diocletian’s ‘lover’ rather than his ‘favourite’, as the film itself calls him. There is also a booklet which includes Tony Rayns’s original perceptive review for Monthly Film Bulletin and an overview of all Jarman’s films by Jason Wood. All of the supplementary material has some interest but it is a pity that the extras do not include Sebastiane Wrap (also known as Sebastiane Mirror Film), a short super-8 film (later blown up to 16 mm) which was shot on location in Sardinia in breaks between the main filming. Its use of a sheet of semi-reflective material either to reflect a blinding light straight back at the camera or to become transparent and reveal a world the other side of the ‘mirror’ links it very closely to the psychological journey undertaken in Sebastiane, with its strange blending of apparently deep spiritual insight with self-blinding narcissism.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to support Jarman’s proud claim that this was a film which ‘altered people’s lives’. It not only exemplified changing attitudes towards homosexuality, it helped to bring about those changes by putting images previously seen only in unlicensed ‘underground’ films into the public spaces of commercial cinema and television. However, the film itself rather subverts Jarman’s other claim that it ‘didn’t present homosexuality as a problem’. Yes, there are some prolonged scenes, shot in a self-consciously ‘lyrical’ manner, sometimes in slow motion, of two of Sebastian’s fellow soldiers, Adrian and Anthony, making love among the rocks and rock pools near the seashore. These two are the first of many of Jarman’s pairs of near-identical male lovers, in which a rather narcissistic self-image is projected onto another person, producing an idealised fantasy relationship which has many connections with the classical and Renaissance rhetoric celebrating male friendship. The friend (and lover) becomes ‘another self’, ‘another I’, ‘the selfsame soul in a different body’ and the many differences which constitute most real-life sexual relationships – differences of age, wealth, power, status, beauty, and sexual proclivity (dominant or submissive) are completely erased.

These idealised and loving twin figures in Jarman’s films usually coexist with other forms of relationship which are even more erotically charged. In Sebastiane the lyrical lovemaking of Adrian and Anthony is intercut with images of Severus ordering Sebastian to remove his boots and in the film as a whole, dominance, submission, and pain (both pleasurable and unpleasurable, both physical and spiritual) are more in evidence than straightforward male homosexual love and sexual fulfilment. Sebastiane may include historically important positive images of male homosexuality but the film is so much more than that and not at all easy to reduce to a political message. In Smiling in Slow Motion Jarman wrote, ‘Positive images are an illusion, like commercials – they are not the stuff of art . . . The great queer artists dealt with negatives, this is why Pasolini and Genet will last long after Gay Times is forgotten in a world of false hope and illusion fed by adverts’. Jarman himself was a ‘great queer artist’ rather than a mere propagandist for homosexuality and this is a beautiful, intense, and troubling film.

About the Author:

Rowland Wymer is Emeritus Professor of English, in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge. He previously taught at the University of Hull. His main research interests are in Renaissance drama, film, and science fiction. His publications include Suicide and Despair in the Jacobean Drama (1986), Webster and Ford (1995), and Derek Jarman (2005), as well as a number of coedited collections of essays, including Neo-Historicism (2000), The Accession of James I: Historical and Cultural Consequences (2006), and J. G. Ballard: Visions and Revisions (2012). His old-spelling edition of the Jacobean witchcraft play The Witch of Edmonton was published in 2017 as part of volume 3 of the Oxford edition of The Collected Works of John Ford, gen. ed. Brian Vickers. He is currently working on a book on Science Fiction and Religion.